Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

1978-79

"Les collines d'Anacapri" (The Hills of Anacapri) is the fifth piece in Debussy's first book of Préludes. Composed in 1909, it was inspired by the town of Anacapri, on the island of Capri in the Gulf of Naples.

The melody imitates bells and contains snippets of tarantella. Two Italian songs are quoted, a chanson populaire and a sultry love song. All these themes merge at the end before a short fanfare, marked lumineux, concludes the piece. One of my favourites.

1978

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, the Italian pianist, has cancelled his United States tour, which included recitals in Carnegie Hall on March 10 and 23. Those holding tickets for the latter can obtain refunds at the Carnegie Hall box office, 154 West 57th Street.

The New York Times (30 January 1978). For April, 1978 three concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Carlo Maria Giulini had been scheduled, in which ABM would play Tchaikovsky, Piotr Ilyich (1840 - 1893), Piano Concerto No.1, Opus 23 in B flat minor.

27-28 June 1978: Musikhalle, Hamburg, West Germany

Debussy: 12 Preludes (Book I)

Michelangeli recorded the first book of Debussy's Preludes for the first time in 1978 for Deutsche Grammophon with Cord Garben [see pp.75ff.] as producer: on this occasion he used two pianos: he played on one, and a wooden peg was installed in the other so that all the dampers did not touch the strings and the strings could vibrate freely. When playing Debussy, the effect of the so-called "Aeolian harp" was created: the strings of the second open piano vibrated freely due to acoustic resonance. Thanks to this effect, the interpretation in this recording achieves a rich sound, a drama that sometimes crumbles the form of the individual preludes. Probably to emphasize the resonance, Michelangeli gives space to pauses and breaths that invite the listener to listen to a distant, ineffable sound in the created silence (characteristic, for example, of Voiles or Le vent dans la plaine). Ce qu'a vu le vent.

But ABM wasn't very happy. So just a few years later, we agreed on a new recording scheduled for November 1985 in La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, without television, and this time with the aim of recording the two volumes of the Préludes.

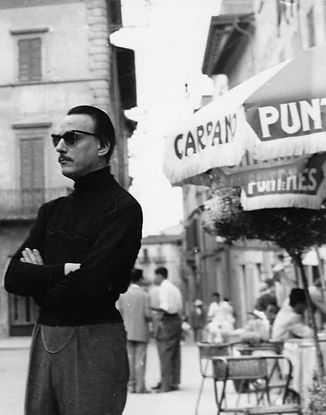

ABM at the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten in Hamburg, where he always stayed in the same suite

11 November, 1978: Salle Pleyel, Paris, France (Radio Broadcast )

· Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, Op.2 No.3

· Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.11 in B-flat major, Op.22

· Brahms: Four Ballades, Op.10

This recital was supposed to have ended with Chopin’s Andante Spianato & Grande Polonaise (Op.22), but Michelangeli didn’t play it because he was “too cold”! Sometimes labelled as 26 October. Indeed, Le Monde diplomatique carries an advert for the 26th and states that the recital is in aid of the National Committee for Leprosy.

Cesare Govi, recalling a brief friendship, wrote in Il Piccolo di Trieste 17 December 1978 under the heading "Only six records but many more voices and legends":

PARIS. Dev'essere tempo di comete, gente mia, state accorti. Qualcosa nell'aria mi sa di presagio, fausto o infausto non so. Un cielo parigino gonfio di nubi da temporale, anche sotto Natale, non è fuori-gioco; però che a promesse di tuoni e saette tenga fede il nevischio è da Fiandra o Baltico.

Il fulmine è caduto a Parigi mentre nevicava, e proprio sulla Sala Pleyel. Il concerto di Benedetti Michelangel è piombato atteso, ma non sperato. E s'è dissolto con profumo di rose come un'apparizione di padre Pio. Un concerto di Arturo Benedetti Michelangel è da anni anche fuori d'Italia un avvenimento da lontana epoca. Nelle regole del gioco è stato invece il piantar lì baracca e burattini, terminare il concerto dopo il primo pezzo. Non è la prima volta: adesso è stato il freddo della sala, le mani gelate non si sono alzate più sulla tastiera come un velo o un rifolo di vento.

Parigi ha incassato bene anche questa impennata d'umore, o di temperatura. Qualcuno ha parlato di ritorsione alla politica francese contro il vino italiano, altri a un'imbron-ciatura perché in quei giorni suonava, lì a Parigi, pure Poliini. Un ragazzo di 57 anni, da 41 primo e unico pianista del mondo, col mondo ai piedi, osannante anche Richter e a Gilels e adesso a Landquist, ma che fa sempre confrontarsi con lui, e a lui si riferisce, si può perdonare una bizza termica.

PARIS. It must be a time of comets, my people, be careful. Something in the air smells like omen, auspicious or inauspicious, I don't know. A Parisian sky swollen with storm clouds, even at Christmas, isn't out of the question; however, whether sleet lives up to the promise of thunder and lightning is something from Flanders or the Baltics.

The lightning struck in Paris while it was snowing, and right on the Pleyel Hall. Benedetti Michelangel's concert fell, expected but not hoped for. And it dissolved with the scent of roses like an apparition of Padre Pio. An Arturo Benedetti Michelangel concert has been an event from a distant past for years, even outside Italy. The rules of the game, however, were to pack up and end the concert after the first piece. It's not the first time: this time it was the cold of the hall, and the frozen hands no longer rose to the keyboard like a veil or a gust of wind.

Paris also took this sudden change in mood, or temperature, well. Some said it was retaliation for France's policy against Italian wine, others said it was a sulk because Poliini was also playing there in Paris at the time. A 57-year-old, for 41 years the world's first and only pianist, with the world at his feet, also praising Richter, Gilels, and now Landquist, but who always makes people compare him to him, and it's to him that one can forgive a temper tantrum.

So many stages and audiences in tailcoats and tuxedos all over the world, excuse me, but before the fantasy—

A puzzling section of anecdotes/legends:

Ma c'era il «qualcosa>> che critica e grossi intenditori scoprivano per la prima volta nei concerti del '46. Un «qualcosa>>> che s'affinava concerto via concerto, l'essenza medesima della Musica e mai sentita finora. «Quel» suono, ovvero quelle sonorità. Ché erano tante assie-mate sovrapposte mescolate fi-no a creare un suono unico. Spiate ai pedali, imboscate e congiure degli occhi per carpirne il segreto nella posatura delle mani e dentro lo strumento dopo i concerti. Niente.

Stavamo per credere a Cesare Tallone, l'accordatore - com'era - che andava sussurrando di miracoli «Ciro prega molto, è tutta grazia e provvidenza la sua musica».

Una notte di maggio a Ravenna dopo un trionfo - eran venuti coi barconi clandestini dalla Juogoslavia, i fans delle famiglie l'antiche dalmato-veneziane per sentirlo in Mozart e e. BenedettiMichelangeli ne fa una delle sue. Quegli sgarbini che gli chiuderanno i salotti più esclusivi d'Italia, ma gliene apriranno altri in Europa. Snobba all'ultimo momento il pranzo dopoconcerto in suo onore in casa Ghigi: lo aspettano fino alle due una cinquantina fra i più bei nomi italiani. Alle quattro - della mattina Benedetti, Franco Gulli, Ettore Gracis, primo violino e direttore dell'orche stra del «Nuovo⟫, Cesare Tallone e io, i carabinieri ci troveranno seduti sui gradini di San Francesco - quattro uomini in frak e un ragazzo in blu - a bere. Quattro bottiglie di Barabera di Montalto Pavese scovato en un' osteria di via Baccerini, cinque calici rimediati in albergo.'

But there was the "something" that critics and connoisseurs discovered for the first time in the concerts of 1946. A "something" that was refined concert after concert, the very essence of Music and never heard before. "That" sound, or rather, those sonorities. Because they were many assembled, superimposed, mixed until they created a single sound. Peeping on the pedals, ambushes, and conspiracies of the eyes to steal the secret from the positioning of the hands and inside the instrument after the concerts. Nothing.

We were about to believe Cesare Tallone, the tuner—such as he was—who kept whispering of miracles: "Ciro prays a lot, his music is all grace and providence."

One May night in Ravenna, after a triumph—fans from the old Dalmatian-Venetian families had come on clandestine boats from Yugoslavia to hear him perform Mozart and the like—Benedetti-Michelangeli makes one of his own. Those sgarbini [rude people] who will close the most exclusive salons in Italy to him, but will open others for him in Europe. At the last minute, he snubs the post-concert lunch in his honor at Ghigi's house: about fifty of Italy's greatest names are waiting for him until two. At four in the morning—Benedetti, Franco Gulli, Ettore Gracis, first violin and director of the "Nuovo" orchestra, Cesare Tallone, and I—the Carabinieri will find us sitting on the steps of San Francesco—four men in tailcoats and a boy in blue—drinking. Four bottles of Barbera di Montalto Pavese found in a tavern on Via Baccerini, five glasses obtained from the hotel.

«Questa Barbera è la grazia e la provvidenza, ragazzi. Non scioglie solo le dita, va dritto in testa, non aiuta a concentrarsi, anzi ti sparpaglia intor no un sacco d'idee, t'ispira li per lì il modo di suonare in quel momento, quella frase; capisci all'improvviso un passo. un sentimento, un'intenzione dell'autore; Mozart, per esempio, non si riesce mai a capir-lo del tutto, c'è sempre un risvolto che l'ultima volta non c'era. Magari un passaggio che suona tutti i giorni da sei mesi». Tallone sentiva un po' blasfema quest'ingerenza del Barbera nelle cose dell'anima, e per esorcizzarla beveva. E' un grosso intenditore dei vini ver-so il lago d'Orta, Ghemma Воca Sizzano Bonarda. Si tiene una bottiglia in una mano e il bicchiere nell'altra. Così ci sor prese l'alba.

' "This Barbera is grace and providence, guys. It doesn't just loosen your fingers, it goes straight to your head, it doesn't help you concentrate, in fact it scatters a load of ideas around you, it inspires you on the spot the way to play at that moment, that phrase; you suddenly understand a passage, a feeling, an intention of the composer; Mozart, for example, you can never fully understand, there's always a twist that wasn't there the last time. Maybe a passage he's played every day for six months." Tallone felt this Barbera's interference in the things of the soul was a bit blasphemous, and to exorcise it he drank. He's a great connoisseur of the wines around Lake Orta, Ghemma Boca Sizzano Bonarda. He holds a bottle in one hand and a glass in the other. That's how dawn surprised us.

'But Barbera, for Benedetto Michelangeli, must truly be a thing of the soul. I remember him sipping and then inhaling lightly while practicing Brahms's "Variations on a Theme of Paganini." Either the dazzling third variation was the work of God or the effect of the Barbera: and since there was a glass there on the piano and a bottle on a chair, I would have no doubts about the attribution.'

"More women than skeletons"

Finora nessuno ha smentito il bacio con cui una principessa di sangue reale, l'avrebbe aggredito durante una lezione, e l'implorazione oramai da un ciclopedia degli aneddoti «Ciro, Ciro, marry me». Scaррò е non la sposò. Sensibili pure le donne di casa Savoia, ma queste son dispeniere di facili glorie: vedi Maurizio Arena. Nascondevano più donne gli armadi degli alberghi dove passava Benedetti Michelangell che scheletri quelli dei castelli scozzesi. Una donna tedesca dopo una notte con lui avrebbe suo-nato a memoria la «Caduta di Varsavia» di Chopin, senza aver quasi mai toccato prima una tastiera: gli avrebbe poi regalato un castello in Tirolo.

So far, no one has denied the kiss with which a princess of royal blood allegedly attacked him during a lesson, and the now anecdotal plea, "Ciro, Ciro, marry me." He refused, and he did not marry her. The women of the House of Savoy were also sensitive, but they are dispensers of easy glory: see Maurizio Arena [Italian actor]. The closets of the hotels where Benedetti Michelangell stayed hid more women than those of Scottish castles. A German woman, after a night with him, allegedly played Chopin's "Fall of Warsaw" by heart, almost without ever having touched a keyboard before: she then gave him a castle in Tyrol.

Marisa Bruni Tedeschi

In the late 1970s, Marisa Bruni Tedeschi had an affair with ABM, which lasted about a year and a half.

[For the full details of the affair, I refer you to her autobiography Mes chères filles, je vais vous raconter (2016). I have mostly tried to select passages - from the Italian translation (2017) - which reveal aspects of ABM's character and life.]

Signora Bruni Tedeschi first met AMB at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris.

'I saw a poster advertising a concert by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Beethoven's Emperor. I didn't realise, at that moment, that I was about to experience the extraordinary adventure of my life.

[Possibly this concert with Sergiu Celibidache and the Orchestre Nationale de France, on 16 October 1974 in Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris.]

'After the concert, I went to say goodbye to him in his dressing room and invited him to our dinner [which she had arranged for Georg Solti who'd given a concert at the Salle Pleyel]. He couldn't; he had to leave for Japan at dawn. He didn't know what to say. I could feel his intense, almost desperate gaze. He picked up all the flowers he had and placed them in my arms. Then he took a bottle of perfume from his dressing table and handed it to me as if it were a jewel. I didn't know then that he had a passion for perfume, until the day I discovered he had a house full of it. It was Jean Patou's "Joy," with jasmine essence, my favourite too. Since then, every time I smell jasmine, I think of him, and also of Virginio who, by a strange coincidence, bought me the same perfume for my birthday. It was his last gift [her son, a photographer, died of HIV related symptoms

at the age of 46].

'Nothing was known about this piano genius. Everything was a mystery. He was born in Brescia, but who were his parents? Who had introduced him to music? A provincial teacher? In those days, there were no training courses abroad, no master classes. Yet, at eighteen, the boy entered the Geneva competition, the most difficult and prestigious, and won first prize. Thus began his international career.

'When I first heard him, I must have been about sixteen. He was as handsome as a Hollywood actor. With his little mustache, he could have rivaled Clark Gable or Charles Boyer. He was simply an archangel, and that's what I want to call him.

Archange [French] appeared in public with that slightly contemptuous air that was his throughout his life, and which made him even more fascinating.'

About two years later (she says elsewhere that ABM was aged 58 at the time)...

'He returned to Paris, to the Salle Pleyel. [1 December 1977 would seem to suit the chronology which is described as roughly two years later; another possible date is October 1978 or 11 November 1978 but at neither recital did he play Debussy; the latter was one on which ABM complained of cold.] His recital nearly got canceled because Archange complained of the cold. Then he played Debussy's Préludes, and they were enchanting.

My husband was in the United States. That morning I had asked my friend Alain Guillon, who worked at the Valmalète concert agency, if Archange would come to dinner at my place after the concert. Alain was sceptical. Archange rarely agreed. Then, after speaking with his secretary, he called me back to tell me that the maestro would be very happy to come. But be careful, he would only be eating plain rice.

'So we returned together, in my little FIAT, followed by his tuner, Marie José, his secretary, his lawyer from Zurich, Affolter, and **Nino Rota, who was passing through Paris [Italian composer, best known for his film scores for Federico Fellini and Luchino Visconti, ( l gattopardo/ The Leopard’ and for Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet]. My mother, Alain, and Roland Bourdin, director of the Salle Pleyel, were also there. When we sat down to dinner, they served him a plate of rice, but he refused it; he wanted to eat like the others. He was cheerful, drank a lot of champagne, smoked one cigarette after another, and left around five in the morning.

**Rota's 1955 opera Il cappello di paglia di Firenze ("The Florentine Straw Hat"), an adaptation of the play by Eugène Labiche, was presented by the Santa Fe Opera in 1977. He also wrote a piano concerto in C major (1960) for Michelangeli, at the pianist's request - but he never performed it.

'Two days later ABM had a concert in Grenoble. Afterwards there was a dinner with all the city's notables, but 'Archange, after a while, got fed up with all the questions they were asking him and said to me: "I've had enough. Let's go drink this champagne in my room."

'A few days later, I received a photograph of him at the piano, with a dedication: "To Marisola, forever."

The relationship developed; here she describes a meeting in Lugano -

'He took me to his house in Sanio, a country house far from town, because Archange liked to live where the roads ended. It was a modest house, a small country villa, with very little furniture, no paintings or books (apart from a Mickey Mouse collection), only a large studio on the garden level with three magnificent Steinway pianos. I was impressed by the fact that every flat surface was covered with medicines: bottles, boxes, syringes, eye drops, poultices, compresses, gauze. And hundreds of bottles of perfume.'

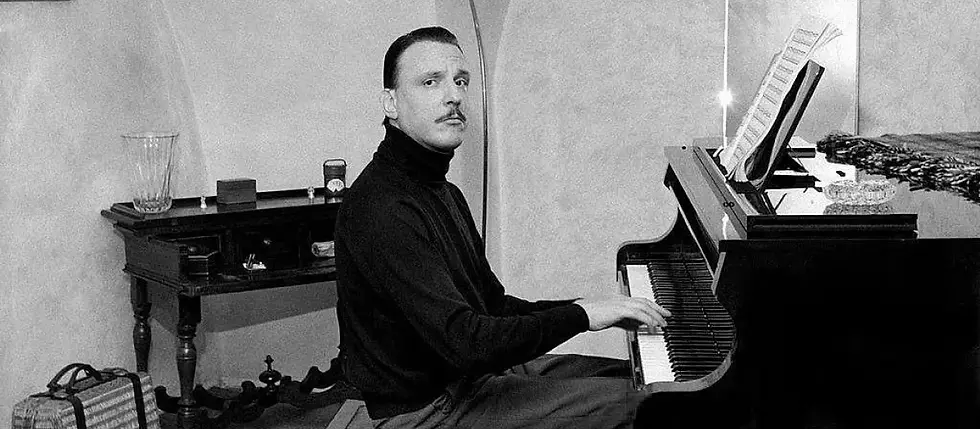

You may have notice the colour of Michelangeli's hands...

'For at least an hour, he had to immerse his hands in a basin of hay flowers (fleurs de foin), a remedy that he considered indispensable for maintaining the beauty of his snow-white hands.'

In the Italian edition:

E poi immergeva le mani in una bacinella con i fiori di fieno, per mantenere la bellezza delle sue mani di pianista.

'Later, in Paris, one evening at a restaurant, my husband said to me: “Listen, I'm not stupid, you disappear for days without giving any news. I might even think you have a lover, but I want to know who he is.” When I revealed the name, there was a moment of silence, then he said sweetly: “I understand.”

'That evening he summoned all his wisdom, like a man facing great danger, facing the wavering will of a woman in love, and he set me free. “Go, come, do what you want. I ask only one thing of you: don't leave your family. I'll be there for you when you need me, because that man will make you suffer.”

Ivan Drenikov (1945- ), a Bulgarian pianist and student. He studied with Panka Pelishek and Pancho Vladigerov in Sofia, and at the age of 18 he received third prize at the 1964 International Competition for Young Pianists "Ferruccio Busoni". Then he studied piano at the Santa Cecilia Academy in Rome, and attended courses with Michelangeli in Bergamo, Lugano and San Bernardo Rabbi from 1968. One source calims he was ABM's favourite pupil (information from various sources including Cronica Sătmăreană , 9 February 1986)

'Ivan never asked permission. He would arrive unannounced, make himself at home, and take possession of the pianos, without the maestro even protesting. No one played Liszt's Mephisto Waltz better than him. Even Archange admired him: "Ivan plays too fast, too fast, but he has good hands." Ivan and I became great friends. In Bulgaria he was one of the "people's artists" and often came to Paris, sent by the Party. His comings and goings were a bit mysterious.'

'One day we were in Sanio and Archange said to me, "Let's go to Rabbi." It was a small village in Tyrol, where he owned two chalets, obviously at the end of the road. A woman, Gemma, looked after them. We set off in her Range Rover. Archange loved driving; he'd even raced. He listened to the engine noise as if it were music, but he refused to stop for anything except petrol.

'When we arrived at the chalet, after an eight-month absence, a mass of mail was piled high: letters from friends, concert companies, music agents, parcels of gifts. I immediately looked for a letter opener, quite curious, but Archange approached me and said, "Want to see?" and threw everything into the fireplace.

'He was a man who loved to inspire enthusiasm in people, and then abandon them. He did the same with his great friends, who continued to write to him, but whom he no longer wanted to see.

He was strange; he told so many stories, I don't know why. He said he was alone in the world, without a family. But, in truth, he had had a wife, whom he never divorced, and who reappeared after his death. And then a brother, first violin in the Angelicum orchestra in Milan, whom I met at some concerts. And also a nephew who was making his debut as a conductor.

'But it became part of his character, at a certain point, to want to ruin the most beautiful things, like a child breaking his toys. He began to lie: "Don't call me for three days, I have to have appendicitis surgery.” In truth, he stayed at home, happy to have told me a lie.'

In an interview with Corriere della sera on the occasion of her 90 birthday, Marisa Bruni Tedeschi explained the end of the affair to Candida Morvillo:

How did it go with Michelangeli?

It lasted a year and a half. I called him 'my archangel.' When I think back, this is one of the things I would relive. I would reach him everywhere, disappear for days. When my husband asked me 'Who is he?' and I told him, there was a moment of silence, then he said, 'I understand you.'

Why did it end?

"Arturo had a rather eccentric personality. Whether it was friends or women, he would suddenly get bored of someone and leave them. He became unbearable, and one night, I left his mountain house, walked 16 kilometers through the woods, and left."

And to Antonio Sanfrancesco, 17 March, 2017 for Il Libraio:

“I would do it all again. It's no coincidence that I put Dante's phrase at the beginning of the chapter [of her autobiography]: ‘Amor, ch’a nullo amato amar perdona’ Inferno V.103, (Love, which forgives no one loved to love i.e. "Love, which does not allow the loved one not to love back"). When I think of passionate love, I immediately think of Paolo and Francesca. All impossible passions are inexorably destined to end, and usually they always end badly.”

A Ivan Drenikov il mio migliore Augurio per la sua vita artistica. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli 1976

To Ivan Drenikov my best wishes for his artistic life. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli 1976

Source: Facebook Ivan Drenikov

1979

Moves to Pura, near Lugano. Recorded live in Vienna Beethoven's Concertos Nos. 1, 3,

and 5 for the DGG with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini.

February 1, 1979: Musikverein, Vienna, Austria (TV Broadcast | Mp4697MB & DVD+R)

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, Op.37

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.5 in E-flat major, Op.73 (Emperor)

– Carlo Maria Giulini / Wiener Symphoniker

– Op.37 in a Mp4 file, Op.73 on a DVD which was originally marked “November 1979: Berlin”. Also another copy of Op.73 on VHS, which was correctly marked.

1 February, 1979: Musikverein, Vienna, Austria (Live Recording | Stereo)

– Deutsche Grammophon –

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, Op.37

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.5 in E-flat major, Op.73 (Emperor)

– Carlo Maria Giulini / Wiener Symphoniker

– Deutsche Grammophon 469 820-2. Cadenzas: L. van Beethoven.

'When in the mood for an Emperor concerto worthy of the handle, I often turn into ABM, live and characteristically imperious in Vienna. Richard Osborne found Michelangeli "all fluster and virtuoso glitter" at the time of LP issue (10/82) but I share the enthusiasm of Charlotte Gardner for the grip and definition of his phrasing as well as the sovereign personality of his immaculately conditioned instrument.'

(Peter Quantrill, Gramophone Awards issue, 2020)

September 15, 1979: Tonhalle, Zurich, Switzerland (Audience Recording | AAC192)

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.1 in C major, Op.15

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 in C minor, Op.37

– Edmond de Stoutz / Zurich Chamber Orchestra

(Thursday 20 &) Friday, 21 September, 1979: Musikverein, Vienna, Austria

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.1 in C major, Op.15 (+ Symphonie Nr. 7 in A major, op. 92)

Carlo Maria Giulini / Wiener Symphoniker

Cadenzas: L. van Beethoven.

Cord Garben notes that the lavish floral arrangements altered the humidity and ABM didn't turn up ["The Maestro seemed to be indisposed"] for the final tech rehearsal on the the day (test for sound, cameras etc.), and that he had to sight-read the piano part.

'Contemporaries tell us that Beethoven's playing of this concerto was brilliant, and stirring, truculent even, rather than delicate; yet pianist of our own time, make him rather more urbane, radical imaginings playing just beneath the effortlessly polished surface. The big third cadenza (of the firt movement) - Tovey's bête noire, played with all the stops out. Scales roll like thunder, minor seconds glint with scarifying brilliance. Midway there is a terrific accelerando and chords black as judgement day; then a trill and a quirky, devil-may-care return to the dominating tune: Arturo Benedetti Eulenspiegel. This is exactly how Beethoven must have treated the solemn-browed cognoscenti of his day. I laughed out loud... The Largo is lucid, lyrical, very Italian. In the great solos, Michelangeli is clear-eyed, a trifle matter-of-fact. There is pathos, but he seems impatient with it. The finale snaps in, proud, expert, very exhilarating, and, by the end, very amusing, genuinely scherzando. I guarantee that 1980, will produce no more thrilling or controversial, Beethoven record and mentally set aside my Austrian Schillings. Meanwhile, in the upper rooms of the Musikverein the shade of Beethoven stirs with pleasure, prompted to recall again the time when he first dazzled and shocked Vienna with his tempestuous music.'

(Richard Osborne, 10/80 reviewing the Deutsche Grammophon recording)

But in September 1988, Stephen Plaistow wrote for Gramophone: I find him a more perplexing artist than ever. Perplexing because he likes to keep his musical personality well hidden – or at any rate, mysterious – behind the armour-plated magnificence of his playing. There is an intellectual froideur about his playing of Beethoven, which verges on the disdainful, and which is sometimes more than off-putting: it is hateful. It is as if we were asked to contemplate the jewelled machinery of his piano, playing as the offer of sufficient pleasure in itself. When the C major Concerto first appeared on LP, Richard Osborne was stirred by it. Two years later, however, he admitted that it hadn't worn well. [SP's view=] It is carved in marble, most of it, and with feeling so externalised and frozen that the effect is chilling. And the slow movement is really pretty awful.

In Algemeen Dagblad (19.2.81), Roel van der Leeuw:

Italian master pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was to record all of Beethoven's piano concertos for a series of televised concerts for DGG, together with the Wiener Symphoniker under the direction of Carlo Maria Giulini. Although Nos. 3 and 5 have already been recorded, the audience will not be able to hear anything more of the entire project than the first concerto, which has now been released, because Michelangeli vetoed the entire project. He is apparently very angry with the conductor, but although I have heard Giulini perform at a higher level, I still consider it not unlikely that the pianist was primarily ashamed of his own playing. It is sloppy, superficial, uncontrolled, and devoid of all poetry. A pity, because Michelangeli is rarely willing to let any of his often masterful playing be heard through concert or recording.

Cord Garben took ABM to the famous Café Leopold Hawelka at midnight for red wine after a Japanese meal. 'Those who work in the circle of a difficult person know no recreation; even the most cheerful atmosphere requires constant vigilance and presence of mind.

To my surprise, ABM didn't have much to say about the recording of the

Piano Concerto in C major. I waited in vain for a comment about the not always perfect correspondence between his rhythmically clear interpretation and the orchestra's performance, which was not always precise, even in and of itself.

But in this case, he would have behaved like his partner, the conductor [Carlo Maria Giulini], like a true gentleman.'

Pura

On 1st August 1979 he went to live in Pura, in the rented villa that some time later he was to leave to another great pianist, Vladimir Ashkenazy. He then moved to a house immersed in the shade of the chestnut groves, just a few hundred metres down the road from the previous house; here he spent the last years of his life, far from the hue and cry and the crowds, in almost Franciscan simplicity. The suffering caused by his precarious health was alleviated by the care and attention of Anne-MarieJosé Gros Dubois, who was also his faithful secretary.

'It remained the owner's secret why he preferred a farm overlooking the enchanting Lake Lugano, devoid of a panoramic view and surrounded by a dense forest, without the possibility of contemplating the water and the distant mountain peaks. But it wasn't just the forest of tall beech trees that hid its secrets. Would a visitor to this isolated world have ever imagined that the walls of the garage that bordered the land towards the road hid a red monster [his Ferrari] who, with its roar, was just waiting for the right moment to bring even the last dreamer back to reality?' [Cord Garben, p.4]

'The first time I was his guest from the 26th of May to 1st June 1975. The house where he lived and worked inspired calm and naturalness. The garden surrounding the house was truly an impeccable fragment of nature. There were trees and a lawn, without excessive intervention of man with his artificial “arrangements”. The house stood on a gentle slope, and so the windows of the Maestro’s study, situated on the ground floor, directly overlooked the garden. There were three pianos in the study. The Maestro gave me permission to try them. One of them was particularly beautiful in its sonorous fullness. Never before, or after, have I had the opportunity of finding an instrument of this kind, or the pleasure of playing it; not even in the concert halls in numerous countries where I have performed.' Lidia Kozubek

'He was very alone in Switzerland. It was an extreme exile, it was too much. It was a sort of self-loathing.' (Mya Tannenbaum [1923-2021], music critic and friend)

Not in Holland

Wednesday/Thursday 10/11 October 1979 were to be with Bernard Haitink/Concertgebouw (music by Hendrik Andriessen, Ricercare; Beethoven "Emperor" Concerto Op.73; Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 1. (Mozart, Violin Concerto No. 3 (K. 216) Jaap van Zweeden replacing ABM on Saturday 13th)

On Sunday 14th, Daniel Weyenberg replaced ABM for a recital at 8:15pm in the Groote Zaal of the Concertgebouw. Michelangeli's programme would have been: Beethoven Op.2/3 in C, Schumann Faschinsschwank aus Wien, Schubert A minor Sonata Op.164 [D 537], Chopin Fantasy Op.49 and Andante Spianato &etc. Concertdirectie G de Koos was the agent, the organisation started by a Hungarian emigré Dr Géza de Koos (who, among many other things, first brought Jorge Bolet to Europe in 1935)

4 October 1979, Algemeen Dagblad announces: The renowned Italian pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli has canceled the concerts he was scheduled to give in Amsterdam next week with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. The young Dutch violinist Jaap van Zweeden will perform in his place.

Hans Heg:

The Italian Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, who was to perform in the Netherlands for the first time next week, has completed his tour. He was to play twice with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and give a recital in the International Piano Series. According to his impresario, he is ill and will not be able to perform for six months. With this, the piano phenomenon, who lives in Switzerland, has confirmed his illustrious reputation

Not so long ago, in Paris, he abandoned a concert because "his hands were too cold." There's also a story going around that elsewhere he refused to venture beyond the wings, as he didn't like the atmosphere in the hall.

The artistic director of the Concertgebouw Orchestra reports that every effort was made to accommodate Michelangeli 's wishes : he would be allowed to bring his own grand piano and his own staff; he would be allowed to rehearse at the Concertgebouw at any time; new orchestral material from Beethoven's Fifth Piano Concerto would be used by the Concertgebouw Orchestra, without notes from previous performances (a requirement Haitink agreed to meet), and three rehearsals would be held.

Michelangeli 's performance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra was not allowed to be broadcast on the radio, just as he also stipulated that no biographical information about him be distributed. This was duly followed up in the monthly magazine Preludium.

Despite all the fuss, it's a shame Michelangeli isn't coming to Amsterdam, because when he's not hampered by mental outbursts, he's still a phenomenal pianist.

De Telegraaf, 12 October 1979

However, I've never experienced so many cancellations, in such a short time, so early in the season," said Johanna Beek of Interartists Concert Management. As for pianist Michelangeli , she believes no one should have had any illusions. "He's the eternal canceler. If you sign him, you can practically assume you'll have to turn the audience away."

"And yet I will certainly try to bring Michelangeli to the Netherlands next year," says Concertgebouw Orchestra's artistic director, Dr. HJ van Royen, who personally engaged the piano virtuoso, aggressively. "He is a difficult, closed man, who actually flees the outside world. He lives in Lugano; but I don't know where yet. I spoke with him elsewhere and I got the impression that he genuinely appreciated playing with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, with Haitink. The exceptional conditions he attached to the performance — he would have his own grand piano;" bringing his own staff, and the Concertgebouw would have to be accessible to him day and night—we took that for granted. Because when he plays, it can be so exceptionally beautiful. The amount of the fee, the point I had actually been most worried about, was not too bad.

In his obituary of the pianist, Roland de Beer in De Volkskrant claims:

'A recital at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw [October 1979?] was cancelled some twenty years ago (in retrospect, it would probably have been his last) because he had spilled coffee on the contract at home.'

Benedetti Michelangeli's Chopin playing

Michelangeli's respect for Chopin is evident in every note he plays. There are none of Busoni's distortions of the composer's intentions - his approach is similar to that of [Carlo] Zecchi, with whom he shares the ability to create a tonal world that establishes an immediate rapport with the listener. In the B minor Mazurka, Op. 33 No. 4, both Michelangeli and Zecchi (who recorded this work twice on 78, once for Ultraphone and once for Cetra) take the opening theme at a relatively slow tempo; in the central chordal passages, Michelangeli portrays the majesty of the music rather than its drama (this belongs to a Friedman), and his reading is distinguished by the delicacy and poise with which he conveys the composer's imaginative ideas. Michelangeli can transform the usually shallow-sounding B flat minor Scherzo into a work of great dignity in which (like Irene Scharrer) he maintains the melodic content of the virtuoso passages, the notes having perfect evenness and an almost miraculous clarity; the work retains its shape and there are no bombastic bass octaves. He also eschews the bravura approach in the Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise Brillante, in which he shows no want of dexterity but succeeds in bringing out the polonaise rhythm with greater originality and wit than any other pianist. The delicacy of the filigree decorations have all the virtuosity of Hofmann, but none of his excessive changes of tempo.

James Methuen-Campbell

Tchaikovsky - will he, won't he?

Vienna's renunciation, however, had its silver lining, since at least we now knew that ABM had the Tchaikovsky concerto in its repertoire or hadat least studied it. So a performance with Herbert von Karajan was within the realm of possibility. What sales potential! Even with such a onerous contract, until now unimaginable in the classical music world, the recording would certainly have generated a significant profit. Unfortunately, ABM's reaction was less than encouraging when I presented him with the proposal. Truth be told, it was quite an expectation, since there was not the slightest chance that either of us would even come close to seeking musical compromises. We could hardly imagine Herbert von Karajan explaining to his orchestra, perhaps shortly before the soloist's appearance, that is, after the end of the rehearsal of the obligatory introductory piece: "Michelangeli is always right, let's play as he wants," as Celibidache had done in Munich before the rehearsal for the Ravel concerto.

To my request, Benedetti Michelangeli responded evasively: "I played with

Karajan at the end of the war. Some recordings must still exist. They were most likely deported to Moscow." He seemed to remember the concert well and that Karajan had rendered it splendid at the time. But the Karajan of that moment, this great medley of sounds that characterized his recordings, would simply have been too far from his

vision. Despite everything, I reminded him repeatedly, always in vain, of this glorious project. I knew from experience that he changed his mind only rarely over questions of content, and if he did, it was with an appropriate temporal shift, so as not to give the impression of defeat. There was nothing he feared more than losing face. He was

unwilling to discuss this issue further. Concerned about my good relationship with him, I then stopped bothering him.' {Cord Garben]