Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

War Years: Part 1 (1940-41)

The Italian Liszt

The outbreak of World War II (1939-1945) interrupted Michelangeli's career just as it had begun. Despite future Queen of Italy Maria José Savoia's efforts to excuse him from the army, Michelangeli was drafted. He joined the Italian airforce, and as soon as the war was over, returned to music. True or false?

Michelangeli has stated that he was a fighter pilot during the war, and a private pilot. But it is certain that he never flew a fighter plane. Nor, apparently, a private plane.

Another example: Michelangeli also claimed to have been a member of the Resistance. But after further investigation, this doesn't appear to be true. He was certainly supported during his military service by high-ranking acquaintances. Some whisper about Maria José of Savoy. But there's no trace of any Resistance.

In some interviews, he stated that his family was of German origin, "Benedikter," and that a grandmother had taken him around Europe, having him study piano with (unspecified) Austrian teachers. He also claimed to be a descendant of the poet/blessed Jacopone da Todi, which is rather convoluted. [Bruno Giurato, April 2018]

(Upon the eventual abdication on 9 May 1946 of her father-in-law KIng Victor Emmanuel III,, Marie-José became Queen consort of Italy, and remained such until the monarchy was abolished by referendum on 2 June 1946, effective 12 June 1946.)

At the end of January 1942, at the height of the second World War, he was enlisted in the Third Medical Subdivision in Baggio, near Milan. Very little is known of his adventurous experiences during the war, the dubious reconstruction of which is entrusted to the testimonies written by several people very close to him.

After 8th September 1943, to avoid the round-ups carried out by the Germans and the subsequent obligation to report for military service requested by the government of the Republic of Salò, he took refuge in Borgonato di Cortefranca, in Franciacorta, as a guest in the castle of the Berlucchi family.

(The Republic of Salò was a German puppet state and fascist rump state with limited diplomatic recognition that was created during the latter part of World War II. It existed from the beginning of the German occupation of Italy in September 1943 until the surrender of Axis troops in Italy in May 1945. The German occupation triggered widespread national resistance against it and the Italian Social Republic, leading to the Italian Civil War. Mussolini, who was ousted from power, had been rescued by German forces and established the I"talian Social Republic "in the north, with its capital in Salò - a town and comune in the Province of Brescia in the region of Lombardy, northern Italy),on the banks of Lake Garda.)

During the following months Benedetti Michelangeli stayed with his wife in Sale Marasino, in the villa overlooking Lake Iseo belonging to the Martinengo family. He remained there until November 1944, when he was forced to evacuate following an airraid which hit the building and, among other things, damaged the first “concert grand” that the Maestro had purchased with the earnings from his first concerts.

He then moved on to Gussago, to the Togni residence, where he was found and arrested by the fascists and taken prisoner to Marone, also on Lake Iseo, to the headquarters of the SS. A few days later, thanks to the intervention of the head of the province of Brescia, Innocente Dugnani, he was transferred to the capital of the province, where he remained for some time, hidden in the loft of the Vittoria Hotel.

Despite the call-up and the war, with its tragic events and vicissitudes, Benedetti Michelangeli was able to continue to carry out a limited concert activity, thanks to the protection of the future queen, Princess Maria José, daughter of Queen Elisabeth the Queen Mother of Belgium, who had appreciated his talent at the time of the competition in Brussels. He played at the S. Cecilia Academy in Rome, La Scala in Milan, the “Maggio Musicale Fiorentino” (Florentine Music Festival) and held concerts in various cities throughout Italy and in Switzerland; he made his first appearance in Barcelona (1940) and in Berlin (1943).

Most of the above from: Pier Carlo Della Ferrera

Michelangeli served in the Italian air force and Alpini during World War II. He ran afoul of the German SS, who, by his account, “rubber-hosed” his arms when they learned he was a pianist. “A minor war wound of no lasting consequence,” shrugs Michelangeli.

Time, 19 September 1960

'He also said he had been a bomber pilot during the war. It seems clear that in this case, Benedetti Michelangeli was "appropriating" his father's wanderings with the South American diplomat and making his dream of military glory realistic.' [Orphaned at an early age of both parents, Giuseppe had been tutored by a South American diplomat who had taken him with him to the various countries where he served.]

Piero Rattalino

'After returning from Geneva (1938), where he had undertaken a successful tour after winning the competition, he was invited to Rome, where he presented his concert to the minister and fascist official Alessandro Pavolini at the Quirinal Palace (the former residence of the Italian king), for which he received a watch and a party card as a gift, which he did not accept.

'Michelangeli's relationship with the fascist party is unclear; he often told his acquaintances that he was part of the resistance (the "Resistenza"), but no evidence has been found to date to confirm this fact. At the outbreak of World War II - at a time when all Italians capable of military service were recalled from abroad - Benedetto Michelangeli was in Paris, where he was to perform a concert for the Apostolic Nuncio Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, who was to ensure his timely return to Italy by the nunciature train - the papal embassy - without the planned concert being canceled. From this meeting, a close friendship was formed between the cardinal and the pianist, which lasted their entire lives.'

Marriage

'The wedding of AMB and Giuliana Guidetti (20 September 1943) took place while they were being evacuated together to Count Martinenga's villa near Brescia. The reason was Michelangeli's hiding place and avoiding compulsory military service, which was introduced in September 1943 in the newly formed Italian Social Republic. Meetings with partisans also took place in the Count's residence, so in 1943 all the inhabitants of the villa were arrested and taken to the SS headquarters on Lake Iseo. Michelangeli was eventually saved from trial by the moderate fascist Innocente Dugnani (head of the province of Brescia). Benedetti Michelangeli himself never actively participated in the battles with the fascists, and it is speculated that this happened thanks to the intercession of the Piedmontese Princess Maria José di Savoia, the future Crown Princess of Italy and daughter of Elisabeth of Belgium, who summoned him to Rome and offered to organize a concert for him.'

'During the war, the new married couple found themselves in a difficult situation, Michelangeli could not teach and only a limited number of concerts were organized, but thanks to Princess Maria José, he was able to play at the Accademia S. Cecilia in Rome in 1942. At this concert, the young Michelangeli played the Allegro by Tomeoni, Variations on a Theme by Paisiello, Sonata Op. 2 No. 3 and Sonata Op. 27 No. 2 by Beethoven, Berceuse Op. 57 by Chopin and Ballade No. 1 Op. 23, Ravel's Jeux d'eau and Debussy's L'isle joyeuse.'

Much of the above derives from a diploma thesis in Czech by Katia Vendrame (Brno 2022), using Giuliana Guidetti, Vita con Ciro & Cord Garben, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli: in bilico con un genio. Cord Garben adds: 'The couple lived first in Brescia, then in Bornato, then in Bolzano and Arezzo, where, in addition to her role as wife, Giuliana also acted as his manager. She managed to shield him almost completely from the public. She herself remained in the background, and therefore only a few knew that ABM was actually married.'

'They were the same age. She saw him for the first time sitting in an armchair in the Pietro da Cemmo hall in Brescia, where she had gone to watch the end-of-year recital of the students of the Venturi Music Institute. When he entered—a young boy who crossed the stage without looking at anyone, sat down on the stool, and began to play the piano ["Era biondo, bellissimo, slanciato e aristocratico nel portamento"], —she, with those absolute feelings that perhaps only children are capable of, decided that when she grew up she would marry him. It was March 1927, they were seven years old: Giuliana Guidetti and Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli celebrated their wedding in September 1943.

“Remember: whatever happens, it will be forever,” said Ciro. He had not lost the nickname given to him as a boy, because of those curls that always remained straight on his head, like Cirillino, the character in Corriere dei piccoli.

'In 1972, two years after the Baslini-Fortuna law came into force [this law, which legalised and regulated divorce in Italy, was approved on 1 December 1970], she wrote to him saying that she would not oppose a request for divorce. He sent her a copy of the Gospels and an anthology of prayers by thinkers from the early centuries of Christianity. Title: Called for Life. There was also a dedication: “You will love them very much.” [«Ti piaceranno moltissimo»]'

Sandro Cappelletto, La Stampa (12 June 1997)

Early on, they lived in a house on Via Marsala, Brescia.

A correspondent Diana (Siberia) has written to me: "Who was the first concert agent for ABM? Have you come across any documents confirming that Rudolf Vedder was the concert agent for ABM in Germany (or is this information just a later invention)"

Giuliana Guidetti recalls...

Una cosa che fece andare in visibilio il nostro gruppo fu quando Benedetti Michelangeli fece il pianista nella Fedora di Giordano al Teatro Grande: l'avevano tutto truccato, era bellissimo, ed era bravo, usciva in palcoscenico e suonava divinamente. A me sembrava il giovane Werther.

'One thing that made our group go wild was when Benedetti Michelangeli played the pianist in Giordano's Fedora at the Teatro Grande: they had him all made up, he was beautiful, and he was good, he would come out on stage and play divinely. To me, he seemed like Young Werther.'

• Do you have any idea how he chose his repertoire?

'I refer to a phrase he often said and which he expressed very well: "You have to know everything, then choose what's worth playing for yourself and what's worth playing in public." For example, he played Tchaikovsky's First Concerto magnificently, but he didn't perform it because it seemed like a "trombone." He did, however, say: it should be studied, and he had people study it. He played Brahms's concertos, wonderfully well, but not in public because he considered them "not very pianistic"; he played Chopin's concertos equally magnificently, but not in public because he found them "too pianistic".'

• He also often played the Absil concerto, the obligatory piece at the Brussels Competition.

'Yes, he once played it at a celebration in honour of Giovanni Anfossi, his teacher, to whom he was very close, as he was with his Milanese professor, Paolo Chimeri, and his violin teacher, Francesconi. The latter criticised him for being too worldly, a playboy. Indeed, he did so a little at first, for example, when he taught for a year at the Venice Conservatory, where he was happy because his two dear friends, Sergio Lorenzi and Gino Gorini, were there, Labroca, the Cinis, the Gaggias, and the Titos. It was a fantastic environment of artists, painters, musicians, and poets who lived "romantically." However, with the humidity of the lagoon, Michelangeli went from one bout of bronchitis to another, and so Nordio, who had been his first director in Bologna, called him to Bolzano, where he lived for many years and where he maintained his residence until

his death.'

Giuliana Guidetti to Alberto Spano (October, 1996)

What? All of them? (Chopin's Etudes)

A recital held in Paris on June 10, 1940, the day Italy declared war on France: it seems that Arturo, to secure a place on the train guaranteed by the Embassy for the return to Italy, had to turn to the Apostolic Nuncio, the future John XXIII.

Who knows if it wasn't that concert that Aldo Ciccolini remembered: "Michelangeli performed the complete Chopin studies in Paris during the war, a concert that I couldn't attend, but he never repeated that experience."

Antonio Armella p.33

Rome début

Despite the call-up and the war, with its tragic events and vicissitudes, Benedetti Michelangeli was able to continue to carry out a limited concert activity. He played at the S. Cecilia Academy in Rome, La Scala in Milan, the “Maggio Musicale Fiorentino” (Florentine Music Festival) and held concerts in various cities throughout Italy and in Switzerland; he made his first appearance in Barcelona (1940) and in Berlin (1943).

On 25 February 1940, he played again in Rome's Teatro Adriano (after his début in December 1939) in a concert conducted by Antonio Pedrotti: the concerto by Jean Absil (from the Geneva competition) and the Grieg.

17 March 1940, Palacio de la Música, Barcelona; conductor José Sabater. Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, with solo works by Chopin. Also Beethoven's Coriolan Overture and the fourth symphony of Schumann. ABM's début in Spain? [Rítmo, 5 May 1940]

On Monday, the 29th of this month, (April) a concert by the young pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli will take place at the Italian Cultural Institute, Vienna.

'The 20-year-old artist, who received his master's degree at the age of 14 and has made his way through the world of music, will perform Beethoven's Sonata Op. 111, as well as works by Scarlatti, Brahms, Chopin, and Liszt.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, a highly gifted pianist, multiple award-winner and now honored with the greatest acclaim by an expert circle at the Italian Cultural Institute, plays Scarlatti's short sonatas so fragrantly and elegantly that one must speak of a mastery. From here to Beethoven's Opus 111 is, of course, a great leap. And even if the spiritual depth still owes something to the joy of technical elegance: we were delighted to experience such a crystal-clear, delightfully unemotional Beethoven, with sharp contours, in a word, one sensed in this interpretation the strong, artistic power of the southerner. Neues Wiener Tagblatt , 1 May 1940

11 May 1940 (afternoon), Sala Bianca del Palazzo Pitti, Firenze/Florence

15 May, 1940: Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

Sergio Failoni, direttore d’orchestra.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (in sostituzione di E. Fischer).

18 May, 1940:

Weber, Euriante, Ouverture; Piccioli, Siciliana e Tarantella; Liszt, Concerto n. 1 per pianoforte e orchestra; Čajkovskij, Quinta sinfonia op. 61; Fritz Zaun, direttore d’orchestra.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.

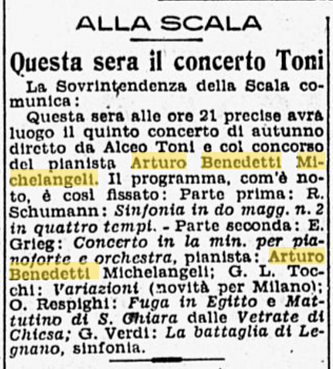

14 October 1940: début in Teatro alla Scala, Milan.

Tickets for the second concert, conducted by Antonino Votto (teacher of Riccardo Muti) and featuring pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangell, will be on sale tomorrow morning at 10:30. The concert will take place on the 14th of this month at 8:30 PM sharp. The programme will be as follows:

L. v. Beethoven: Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major (op. 73) for piano and orchestra; G. Martucci: Nocturne in G-flat; Albeniz: Triana (from the Iberia Suite); Liszt: Danse Macabre [Totentanz] (paraphrase of the Dies Irae) for piano and orchestra; Ottorino Respighi: The Pines of Rome.

Wednesday, 20 November 1940, Victoria Hall, Geneva, with Ernest Ansermet. 'The enthusiasm that this young artist provokes is fully justified at each of his appearances, as his admirable talent is always shown in all its perfection. For him, we can rightly use the description that Camille Mauclair attributes to the piano: "A white and black magic." For Benedetti's art is truly a magic. Magic of an absolutely unique pianistic touch, of an enveloping and warm softness, fluid, crystalline, but also a touch of exceptional firmness, deep, without violence and of impeccable clarity. Magic of an unrivalled technique, magic of colors, of sonorities and magic of lively, warm, expressive interpretation and yet always under the control of a mastery and a calm and absolute authority. The two works performed by the incomparable artist were those that could highlight his miraculous gifts. Liszt's Totentanz/ Danse Macabre, with its rhythmic power, its strong descriptive evocation, and Grieg's Concerto in A minor, a magnificent romantic outburst by Benedetti, enjoyed a just triumph. And to think that this piano magician, who is calm and sober before the acclamations that rise towards him, is only 20 years old! The program of this concert also included Haydn's Symphony in E flat, one of the best, and La Peri, a symphonic poem by Paul Dukas.'

Courrier de Genève, 21 November 1940

Budapest, December 1940

Pester LLoyd, 1 December 1940: Benedetti-Michelangeli also captivated the Budapest audience on his first evening (30 November). On December 5th, he will give his second piano recital. The new programme includes Bach—Busoni: Chaconne, Balakireff: Islamey, Chopin series, Debussy, Liszt.

The first recital:

“Ein musikalisches Phänomen. Der Klavierabend von Michelangeli”

It is impossible to describe the musical talent of the barely twenty-year-old young Italian pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangelo as anything other than a musical phenomenon. Those enthusiastic reports about his wonderful successes at the Florentine Maggio Musicale proved completely true yesterday evening at his first performance in Naples.

‘His psycho-physical characteristics alone predestine Arturo Benedetti Michelangelo to be a master of the piano: a hand born to be a pianist, with extraordinary range and elasticity, a youthfully vigorous organism of controlled strength and, finally, a nervous system of astonishing endurance and discipline; These are excellent qualities that make our artist one of the most "astonishing" pianistic talents of our time.

One might think that, in possession of such a gift, we are confronted with a youthful "storm and stress" (Sturm und Drang), a romantic hothead, who plays with the youthful impetuosity of his twenties, revealing either the sensitive romantic or the self-important virtuoso—for which, incidentally, he certainly possesses the technical capabilities.

What is astonishing, beyond all else, is the unparalleled intellectual discipline of his performance, which is nothing but classically solid in the best sense of the word. mature in conception. Any obtrusive esprit de corps is avoided in order to allow the great breath, the expression of the phrase, to stand out all the more monumentally. The tempi are grasped with exemplary precision and executed with iron consistency. The motif of entire movements is presented before us with exemplary clarity, something we find entirely natural in a son of "Italian" soil, the home of his great namesake, Michelangelo. The parallels to the visual arts are particularly evident in this divinely gifted designer; the liveliness and clarity of the architecture, the organic structure of large, harmonious surfaces, are among the most striking features of his piano playing. This performance has style in the best sense of the word.

This specifically classical-Italian trait of his character in no way detracts from the universality of his comprehension, the comprehensive nature of which was already demonstrated by the compilation of Saturday's program. Anyone who can perform the late Baroque Sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti, the B-flat minor Scherzo of Chopin, the mighty C major Sonata Op. 2, full of Beethoven, or the Paganini Variations of Brahms with consistently consistent mastery, not only of the technical aspect, but also with this unprecedented intensity of intellectual habitus, is truly a universal artist. --* The evening's program was clearly designed to document the special versatility of the

phenomenal artist ad octilos

It was indeed a complete success; one didn't know what was more admirable about the performance: the sparkling fluency of the Scarlet Sonatas, which seemed to be thrown at me quite effortlessly, the classically captivated and yet highly expressive poise in the Beethoven Sonata (where the inner passages of the Adagio and the Scherzo, as well as the sparkling Finale, are highlighted as particular highlights), the somber, gloomy, and melancholic choral performances of the Beethoven Sonata, not to mention the mighty Paganini Variations by Brahms, the stupendous virtuosity of the minor works (Chopin Etudes, Polonaise by Liszt). It is almost unbelievable how a young man of barely 20 years of age was able to attain such a classical height of pianistic expression, which even made the performance of Chopin's Scherzo appear to us as a kind of classical music. In comparison, the fact that, for example, the tempi of the Chopin etudes were taken a little too quickly in youthful practice must be completely secondary in importance. The audience, who cheered ecstatically for the youthful phenomenon and demanded a whole series of encores from him, left the concert hall with the blissful feeling of having heard one of the greatest piano artists of our time. Indeed: when one listens to Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli's playing, one can perhaps get an inkling of the feeling with which, about 100 years ago, contemporaries may have listened, breathlessly captivated, to the appearance of the young Liszt.

Dénes Bartha (1908–1993), the internationally renowned Hungarian music historian, known for his research on Joseph Haydn, worked as a music critic for Pester Lloyd between 1939 and 1944. He also played an important role in folk music research when Béla Bartók entrusted him with editing the booklet accompanying a set of gramophone recordings: A magyar népzenei gramofonfelvételek programja. From the 1949 communist takeover onwards, his opportunities in Hungary became increasingly limited and he was somewhat sidelined behind his also excellent colleague, Bence Szabolcsi. The articles that Dénes Bartha wrote in German for Pester Lloyd between September 1939 and June 194414 comprise a very important part of this colourful oeuvre. The newspaper, founded in 1854, was the daily of the German-speaking bourgeoisie of Pest, and the high quality of the cultural section is reflected in the fact that in the 1930s and 1940s writings of such significant authors were published here as Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, Felix Salten and Stefan Zweig, as well as Hungarian writers Dezső Kosztolányi and Ferenc Molnár.

Olaszországban feltünt az "uj Liszt Ferenc"

Pesti Hírlap 1 September 1940

'The "new Liszt Ferenc" appeared in Italy. At the beginning of the summer, a report appeared in the Pesti Hirlap about the musical events of the festive games in Florence. The writer of the report, Countess Ceruttiné Paulay Erzsi (gróf Ceruttiné Paulay Erzsi) dedicated extremely warm lines to the praise of an 18-year-old Italian pianist, Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli. "Let us remember this name well," she wrote, "because the pianist we have been waiting for for years has arrived!" Other Italian and foreign press voices also confirm that a completely extraordinary phenomenon has appeared in the field of musical performing arts. This year, our audience will also get to know the young artist, the great winner of the Zurich [sic] piano competition two years ago; whom the great Cortot directly compared to Liszt Ferenc. In December, Benedetti-Michelangeli will organize a debut evening.

Pesti Hírlap 1 December 1940

Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli . . . is not an easily remembered name, but our audience will soon learn it Our readers may have already noticed it, because in these columns Countess Ceruttiné Paulay Erzsimár [= Erzsi Paulay, Hugrarian actress married to Italian ambassador Count Vittorio Cerrutti] wrote an interesting report about the young Italian pianist, who was celebrated as the “new Ferenc Liszt” by the audience of the Maggio Musicale in Florence this year. Surprised delight easily leads to exaggeration, but even moderate criticism must conclude: this twenty-year-old, slim-waisted, clean-faced, dreamy-eyed young man is a phenomenal talent. [ez a húsz esztendős, karcsú derekú, tiszta homlokú, álmodozó tekintetű fiatalember tüneményes tehetség] The piano and he were made for each other. The instrument, wholeheartedly and enthusiastically, with all the magic dormant in it, with its entire magical repertoire of tones, shades of power, shimmering runs, octave themes, chord cascades, trill wonders, surrenders to its young master, offering him all this wealth, let him flourish in it as he pleases. Is it possible to resist such a temptation? Our artist does not abuse it unbridledly — he probably instinctively feels the responsibility of his talent — but he cannot even maintain sufficient order among his natural treasures. In Beethoven, here and there, an etude-like self-interest, elsewhere an overdriven tempo, or an emotionality that has not been experienced, and therefore seems sentimental, can be blamed as his faults. But there are cases, as in the Chopin scherzo, where the very immaturity of the conception promises a classicizing interpretation free from any romantic mannerisms. All in all, an extraordinary technical prowess reminiscent of Horovitz awaits the full development of the artist's individuality. The dizzying performance of one of the Scarlatti sonatas, the two Chopin etudes and Brahms' Paganini variations made the Benedetti-Michelangeli debut an extraordinary concert experience.

L. V.

Second recital: The outstanding pianist began his concert today in the Redoute [= Vigadó, Budapest] with a charming little work by Tomeoni (18th century). From the very first bar, the listener is enchanted by the floating lightness and the subtlety of the nuances in Arturo Benedetti-Micheangeli's playing. The vivid voice leading is as clear as the beautifully rounded formal structure. His dazzling and unerring virtuosity knows no bounds, as was also demonstrated by the serious and balanced rendition of Bach-Busoni's Chaconne. With the elegant assurance of a grand seigneur, he commands the passages, the octaves, and the chords, letting the tones roar tempestuously without showing the slightest effort or fatigue. Listening to these passages, one has the impression that everything is far too easy for him and that he could play even the most difficult passages just as effortlessly, and with his characteristic superior calm, twice as fast. This sovereign mastery of technique, in this absolute perfection, would offer considerable aesthetic pleasure in itself. In addition to this astonishing virtuosity, there is also a high level of musical culture that lends value and significance to this pianist's interpretations. He also has a particularly fine sense of sound and expressive phrasing, which his Chopin playing demonstrated. The Berceuse was a delicate whisper, softly passing by like a gentle breath of the warm, fragrant spring breeze. The F minor Fantasy was sweeping and brilliant, and the C sharp minor Étude, which he performed as an encore, set a tempo record that will probably be difficult to surpass. On the piano, Benedetti-Michelangeli has a velvety touch, and he knows how to conjure tonal subtleties and nuances from the instrument that are rarely encountered.

"Islamey" by Balakirev. This composition, which we had remembered as a not particularly entertaining or interesting work, was now unrecognizable. Benedetti-Michelangeli transformed it into a glittering (and also thunderous) firework of astonishing feats, playing them colorfully and charmingly, with a springy, idealistic rhythm, with fiery temperament, but above all with unparalleled pianistic bravura. Thunderous applause thanked the outstanding young artist.

Pesti Hírlap 6 December 1940

There is something, barely expressible in words, light and yet meaningful, transparent and yet profound, in the piano sound of this young Italian artist. In some places — the artist is barely twenty or so years old — he can almost perform miracles. In the pre-classical pure piano style, in Tomeoni’s “Fuga and Allegro”, he realises the ideal of beauty of sound. The resonant splendour of Busoni’s Bach-Chaconne transcription was also able to approximate the sound experience that the original idea provides on the violin. Debussy’s “L’Isle joyeuse” or Liszt’s “Eglogue” were a veritable parade of colour effects. Of course, there are still heights that he cannot yet approach so closely. Chopin... The meticulous calculation of the "Berceuse", for example, was already somewhat bordering on the boundaries of ?flask music [a lombik-zene]. But this is not due to the artist's knowledge, but rather to his chords. At Benedetti Michelangeli's second piano recital, we already saw part of the audience that is "officially" present at every major concert event. As if the other part still had doubts, whether to believe the artist's reputation? We can reassure the doubters: Benedetti Michelangeli's piano recitals will be major events in the musical world within a year or two. (mja)

There were two concerts with Herbert von Karajan in Berlin in December 1940 – the Grieg concerto was performed (Karajan's concertography: 8 & 9 December 1940).

1941

On 5 February 1941, L'Avvenire d'Italia reported on a recital in the Liceo Musicale, Bologna :

'Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli undoubtedly possesses a privileged nature. In him, virtuosity blends with temperament and the refinement of an acute and remarkably responsive sensitivity. His technique is extremely solid, rational, logical, complete, and constructive; governed by an inner control that elevates it to artistic thought and will. His sound can be, depending on the case, very sweet and powerful, diluted and solid, transparent, crystalline, robust and metallic.

'But Benedetti the artist is something more than Benedetti the virtuoso. He feels music in a very personal, intuitive, simple, and lucid way. A subtle engraver, revealer of every idea and of the great formal and constructive lines of the composition he performs, each of his interpretations seems to pass through the filter of a fervent intellect and a sensitivity that vibrates at even the slightest call.

In lui il virtuosismo si fonde con il temperamento e con la raffinatezza di una sensibilità acuta e prontissima. La sua tecnica è solidissima, razionale, logica, completa, costruttiva; regolata da un controllo interiore che la innalza a pensiero e volontà d'arte. Il suono sa essere, a seconda dei casi, dolcissimo e potente, diluito e solido, trasparente, cristallino, robusto e metallico.

Cesellatore sottile, rivelatore di ogni idea e delle grandi linee formali e costruttive della composizione che esegue, ogni sua interpretazione sembra passare attraverso il filtro di un fervido intelletto e di una sensibilità che vibra ad ogni pur tenue richiamo.

'Benedetti amazes in the tumultuous transcendence of his technique no less than he captivates in the sweetness of his most tender, romantic, intimate pages of fantasy and feeling (let's even say this word that makes us shudder so much today!).

Benedetti stupisce nelle tumultuanti trascendentalità della tecnica non meno che avvinca nella dolcezza delle pagine più tenere, romantiche, intime di fantasia e di sentimento (diciamola pure questa parola che oggi fa tanto rabbrividire!)

And whoever yesterday listened to Chopin's "Berceuse", Respighi's "Nocturne", Beethoven's Adagio, should question his memory and cannot help but admit that he felt a profound and moving emotion.

'The programme included a Fugue and an Allegro from the eighteenth-century Tomeoni (pieces reconstructed and elaborated by Benedetti himself with taste and stylistic propriety); Beethoven's Sonata Op. 2 No. 3; Chopin's Berceuse and Scherzo in B-flat minor; Martucci's Tarantella; Respighi's Nocturne; and Balakirev's Islamey.

'And the success, as expected, was resounding and enthusiastic: at the end of the concert, a veritable frenzy of cheers and ovations was quelled only by the kind concession of numerous unscheduled pieces. A huge crowd was present, the hall packed to the brim.'

4 March 1941, Madrid

At the Teatro Español, pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli achieved his usual success, already a favourite with the Madrid public, with a program that included Beethoven's "Third Sonata in C Major," Brahms's "Variations" on a Theme by Paganini, and several works by Chopin and Liszt. (Ritmo XII, No.143)

20 March, 1941 Pamplona, Spain: Grieg Concerto, conducted by [Fermín?] Muruzábal. Encores included Tarantella Napoletana Op. 44, No. 6 (1879-80) by Giuseppe Martucci, and Scarlatti sonatas.

7 April 1941, Madrid , Spain

In the splendid Teatro Coliseum, a piano recital was given by the man we do not hesitate to describe as a leading contemporary figure in the art of piano, Arturo Benedetti-Michelangell. There may be some virtuosos as good as this pianist in our times, three or four at most; better than him, we understand that none exist. He is a marvellous case. He is a true phenomenon. He is... musicality and piano technique made man and, if anything were missing, a man in the prime of his juventus, that is, one who has a long life ahead of him to dedicate to his art. It is frightening to think to what extremes Benedetti will be able to take his mastery of the piano; today, it is inexplicable that this astonishing security that leads him to interpret more and more works, the most difficult ones, those with the most intricate technique, without ever hitting a key wrong or violating for a single moment the precise intensity of the sound or the section of the rhythm.

Hoja del Lunes, 7.4.41

Saturday, 8 November 1941

Délmagyarország

20 October 1940