Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

1950s & South Africa

"Unlike some other post-war importations such as Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Glauco D'Attili, Aldo Ciccolini does not seek to dazzle with technique alone, or primarily."

New York critic Irving Kolodin,

The Buffalo News (2 November 1951)

'In the 1950s, a period of very intense concert activity except for the parenthesis in 1954, when Benedetti Michelangeli was forced into complete retirement for health reasons (symptoms of tuberculosis), we note the exclusion from the repertoire of many composers he had touched on in previous years and the focus of interest on Mozart, Chopin, Debussy and Ravel. He renounced the more spectacular compositions (for example, Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 in C# minor - beloved of Josef Hofmann [and Jorge Bolet] - and Balakirev's Islamey , of which there are no recordings or recordings) and instead showed a certain interest in contemporary music (Ballade by Frank Martin, Concerto by Mario Peragallo, Kinderkonzert by Franco Margola, Concerto No. 4 by Rachmaninoff, Suburbis by Frederic Mompou)'.

(Piero Rattalino)

For the visits to the Laverna/La Verna monastery, see here

At the turn of the 1950s, Michelangeli played with conductors he would never meet again: Furtwängler and Karajan. Unfortunately, no recordings of these concerts have survived. In October 1948, Michelangeli was in Edinburgh, where he had the opportunity to play Beethoven's Triple Concerto with conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, and this was not their first collaboration, as they had already recorded some records together during the war years, but these were unfortunately lost somewhere, as well as as a recording of a concert that took place in Berlin with Furtwängler's younger Austrian colleague Herbert von Karajan, unfortunately its exact date is not known either.

The Edinburgh concert took place on 8 September 1948 at Usher Hall with the orchestra of the Academy of S. Cecilia, the program also included Symphony No. 2 by J. Brahms, Anacreon Overture by Cherubini and Beethoven's Overture. "Leonore" II. Beethoven's Third Concerto was played by violinist Gioconda de Vito and cellist Enrico Mainardi

Katia Vendrame (Brno, 2022)

Meanwhile, in 1950, he had obtained a transfer to Bolzano, called upon by the Director of the “Monteverdi” Conservatory, maestro Cesare Nordio, with whom he founded the “Busoni” piano competition in 1949.

He taught in Bolzano until 1959, supplementing the state courses with those of the private specialisation school he opened in Paschbach Castle, near Appiano, in an attempt to meet the numerous requests from pianists all over the world already holding diplomas, some of whom had already won important competitions, and had consequently not been admitted to the conservatories. His assistant was Isacco Rinaldi.

Paschbach Castle above San Michele Appiano, Via Monte / Bergstrasse 33. Castel Paschbach (in German Schloss Paschbach) is a castle located in the hamlet of San Michele in the municipality of Appiano in South Tyrol; 9km from Bolzano. The first written documents that speak of this manor date back to 1248, when it consisted only of the so-called "Torre di Pasquay".

'In 1570 the castle was purchased by Jakob Aichner, who in 1585 had it enlarged in the Renaissance style by Luca d'Allio. It remained in the hands of the Aichner family, which in the meantime had been invested with the noble predicate "von Paschbach", until the end of the 17th century when it passed to the lords of Mörl. In the 19th century it became the property of the Wohlgemuth and then passed from hand to hand to the current owners.

After the Second World War, it was the home of the pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, who also taught master classes there. His piano is still preserved in the castle. The property includes a tower which houses a Gothic stube with original walls covered in wood.'

'In 1950 ABM moved to the Bolzano Conservatory, where he taught until 1959, also holding a specialisation course in the castle of Appiano. His presence, however, due to his many concerts and also to his restless character, did not have the continuity that regular teaching required. Interviewed for the catalogue of the 1997 Bolzano exhibition, Vea Carpi, director of the Conservatory whose house – as a child – Michelangeli frequented (her father Giannino was a violinist, her mother Gabriella was a pianist) said: "He had the keys to the Conservatory; he was capable of staying there all night studying and studying some more.

'Then at dawn he would leave and not be seen again until, perhaps days and days later, he remembered he had a lesson. It went on like this until the day this 'freedom' was made to weigh heavily on him—I don't know at what level, whether ministerial or local—and he was asked to respect certain rules. It was from this that he felt deeply offended and made the decision to leave. We never saw him again." Vittorio Albani specifies: "Over the years, however, due to his intense concert activity, his presence at the Conservatory would become increasingly sporadic, until, at the end of 1959, he was forced to ask for a twelve-month leave of absence. In the meantime, Director Nordio, to meet the concert pianist's needs, requested and obtained from the Ministry of Education the establishment of a high-level international piano course for him. However, this authorization arrived on January 8, 1960: too late." Benedetti Michelangeli expressed his displeasure in writing to Director Nordio and sent for his Petrov piano to be collected, specifying that it was in Room 21.

'There, among other things, between 1950 and 1952, he had taught the young Maria Cristina Mohovich, the only "survivor" of a class that initially consisted of seven students, and whom Michelangelì selected. Professor Mohovic recalls:“Years of assiduous and exhausting study. His high professionalism, his rigor, his absolute devotion to art allowed no concessions whatsoever, nor any kind of victimization or self-pity. I remember one day when he addressed me about a Liszt study, still rather 'battered' (...). I timidly replied that I had done my best, working – as I usually did – my seven hours a day. He replied sternly “...that's not enough! At least eight... a day is made up of twenty-four hours: eight for studying, eight for sleeping and eight more left... for having fun”. Maria Cristina Mohovich, still living in Bolzano (2011), is the only pianist who obtained her diploma with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.'

1950

New tour of Canada and the United States.

Michelangeli gave a recital in New York's Carnegie Hall on 20 January, 1950 with the repertoire he had been playing in those years. The programme of the evening concert at Carnegie Hall included two pieces by Fryderyk Chopin, Valses nobles et sentimentales by Maurice Ravel, and the rest consisted of pieces by Italian composers, which were unknown to the vast majority of listeners. As the correspondent Giusti notes: 'Michelangeli did not present himself with any piece "for effect" that would allow the pianist to show his virtuosity.'

"Scarlatti e Michelangeli fanno delirare gli Americani." Corriere della Sera. 2/3. 3. 1950.

'The first part of the concert featured Presto by Galuppi, Adagio by Grazioli, Capriccio by Paradisi, and the whole was concluded with three sonatas by Scarlatti, between which Michelangeli hardly stopped, because he did not want applause between them - he probably considered them as one whole. The concert closed with Grande Polonaise brillante by Chopin, there were three encores after the main programme; they also included a composition by Francis Poulenc.

Musical America reported:

The Italian pianist Arturo Michelangeli, who made his American debut last season, gave a second Carnegie Hall recital that reaffirmed his position in the musical firmament. Not yet thirty, his pianism was masterly. If there was a certain lack of warmth, of mellowness, on occasion, there was more than enough to compensate for it in Mr. Michelangeli’s acute formal sense and his marvellous precision of detail.

Mr. Michelangeli’s sovereign technique permitted him the luxury of opening his program with the Clementi sonata. His musical sensitivity uncovered its Beethovenian aspects. The harpsichord works that followed were superbly delicate, and exquisite in structure. The powerful, yet controlled, sweep of the ensuing Chopin sonata came as a striking contrast. The first and last movements were nothing short of magnificent. In the first, Mr. Michelangeli achieved a grandness and lyricism that allowed no place for dubious sentiments. Its short developmental section was consummately clear, making the kind of musical sense few pianists can find and project. The quiet, unaccepted desolation of the last movement matched it. The Funeral March, and parts of the Scherzo, were beautifully songful, although Mr. Michelangeli emphasized the melody at the expense of other voices. The Ravel waltzes were, simply, noble and sentimental, and the pianist wound up his brilliant recital with a stunning account of the Andante and Polonaise.

The Carnegie Hall performance was followed by concerts in St. Louis, Washington, San Francisco, and other American cities.

In the Chicago Tribune, 8 March 1950, Claudia Cassidy ("The Harpy of the West") noted that the Italian pianist was too ill to play his recital last night in Orchestra Hall. A telephone call reached Moura Lympany in New York at 3.15pm, an obliging plane set her down in Chicago at 7:30. 'By 8:30, auburn hair shining, crisply embroidered white dress rustling, she was sitting down at the piano.' [Miss Cassidy was not impressed by the recital, however!]

The pianist had stayed in the United States for almost two and a half months but the tour was now abruptly cancelled; the plan had been for him to give concerts in Australia and New Zealand, but this never happened.

29 June, 1950: Teatro dell'Opera di Roma - recital.

Bach- Busoni – Toccata and Fugue in D minor BWV 565.

D. Scarlatti – Four Sonatas.

M. Clementi – Sonata No. 1 in B flat major, op. 12.

F. Chopin – Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor, op. 35.

C. Debussy – Reflets dans l'eau and Hommage à Rameau (from Images book 1).

M. Ravel – Valses nobles et sentimentales.

F. Chopin – Grande Polonaise brillante op. 22.

At the Venice Festival on 11 September 1950, ABM performed Mario Peragallo's Piano Concerto and Orchestra with Carlo Maria Giulini.

'There were those who whispered to us about communism and capitalism this evening at the Fenice, alluding (we seem to have understood) to the political beliefs or economic conditions of some of the three great Italian composers presented at the Festival's third symphony concert. May the informants forgive us: their information was wasted. The brand-new music by Mario Zafred, Guido Turchi, and Mario Peragallo didn't actually carry any visible label. In return, it was intelligent music. Indeed, very intelligent.

'Mario Peragallo. More intellectual than Zafred, more closely tied to the twelve-tone system than Turchi; of the three, perhaps the most arid and subtle, despite the sum of the phonic values employed, in this Concerto for fortepiano and orchestra, to support or frame the solo instrument. In reality, it offers little interest as a concertante element on the piano, while it offers significant interest as a colouristic element among colours and a timbric element among timbres, or, where lyrical inspiration takes hold, as a melodic element. The construction is compact, yet agile and not devoid of a certain elegant decorativeness that lightens the predominantly severe, if not harsh, lines.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli played Peragallo's work superbly. Carlo Maria Giulini conducted the entire program, once again performed by the Rome Radio Orchestra, with love and, more importantly, with confidence and command.'

Franco Abbiati, Corriere dell Sera 12.9.50

22 December, 1950, Teatro Argentina, Rome

Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Ettore Gracis, piano: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli

Salieri Symphony in D major "Veneziana"

Beethoven Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 73, "Emperor"

Peragallo Concerto No. 1 for Piano and Orchestra (1949-1950)

Liszt Totentanz, for piano and orchestra R 457

Rossini's The Barber of Seville was given its premiere here on 20 February 1816; Verdi's I due Foscari on 3 November 1844

1951

16 February 1951, Teatro Comunale di Bologna: Haydn: Symphony no.101 – “Clock”

Mozart: Piano Concerto in Dm K466 (Soloist: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli)

Strauss, R: Till Eulenspiegel. Herbert Albert

Galuppi and Scarlatti were not the only Italian composers that Michelangeli played around the world in those years: from 1951 on his tours he also presented the 1949 concerto for piano and orchestra by his friend from Venice, Mario Peragallo (11 May 1951 in "G. Verdi" Conservatory in Turin with Carlo Maria Giulini. ' I listened to the concert on the radio and

heard the resounding boos that greeted the performance of Peragallo's Concerto. Why,

given that ABM knew his aficionados so well, did he provoke them so seriously? Andrea della Corte wrote: "Many listeners wondered why Benedetti Michelangeli persists in touring this Concerto, he who associates with great artists and almost entirely excludes the music of other contemporaries, whether equal or superior to this one.)" The

reference to Prokofiev, Bartok, and Stravinsky is clear, although not expressed, and in my opinion pertinent.

(Piero Rattalino).

His interpretation of this piece was recorded by the State Radio Company – RAI, but to this day these recordings have not been published. Among other things, the concert was played in the Vienna Konzerthaus on April 10, 1951. This piece uses dodecaphony, and one can hear the influence of Arnold Shönberg with more neoclassical elements.

In Venice on September 11, 1950, he played this concerto for the first time with conductor Carlo Maria Giulini as part of an evening performance of contemporary music, where compositions by Zafredo and Turchi were also performed. The day before, as part of the same festival, a concert with pianist Marcelle Meyer took place, who played a concerto by Veretti. Source: ABBIATI, Franco.

Il Festival della musica. Zafred, Turchi e Peragallo diretti da C. M. Gulini. Corriere della Sera. 12. 9. 1950. Some sources give the year 1949 (GARBEN, Cord. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli: in bilico con un genio. Translated L. Seuss. Novara: Zecchini editore, 2004, p. 105 (222) but here differently: Wiener Symphoniker. 10. 4. 1951. Dienstag 20 UHR [online]. Wien: Wiener Symphoniker, 2022 [Cit. 27. 2. 2022].

Katia Vendrame

10 April 1951, Konzerthaus, Vienna; a mixed concert in which ABM performed Mario Peragallo's Piano Concerto

"Ein Überlebender aus Warschau" für Sprecher, Männerchor und Orchester op. 46 (Österreichische Erstaufführung) Arnold Schönberg was also on the programme. The Wiener Symphoniker was conducted by Hermann Scherchen. ABM would next play here with this orchestra in June 1975.

18 May 1951, Bologna

Sinfonia K. 385; Mozart, Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K. 503; Sinfonia K. 181; Concerto per pianoforte e orchestra K. 450.

Orchestra dell’Ente pomeriggi musicali di Milano.

Ettore Gracis, direttore d’orchestra.

He'd played K. 503 a few days earlier in the Teatro Verdi, Trieste, on 14th with Luigi Toffolo, along with Beethoven's "Emperor". Luigi Toffolo, 1909-2004, a native of Trieste, studied piano with Gastone Zuccoli and had some lessons in composition from Antonio Smareglia, composer of opera “Nozze istriane”. One of only three of Toffolo’s “official” LP recordings is about as unexpected as can be imagined. For Hungaroton, he set down a suite from Ferenc Szabo’s “Ludas Matyi” with the Hungarian State Orchestra.

Salzburg Festival, Austria, July 26, 1951.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli had to leave because of a sudden illness. Organisers managed at the last minute to secure the important French pianist Monique Haas his place for the first solo concert on 31 July at the Mozarteum. One even hopes that Monique Haas at least partly play the same programme that Benedetti-Michelangeli had announced. (Weltpresse)

The third Salzburg soloist concert was dedicated to improvisation: Claudio Arrau was ill. Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli had, as expected, once again confirmed his participation and then canceled again, and Klara Haskil's participation could only be confirmed and announced late. This affected both the attendance and the orchestral part of the evening (Mozart Orchestra, conducted by Bernhard Paumgartner). Mozart's piano concertos are not as "gratifying" as pieces by Chopin or Liszt. A perfectly played Mozart is always Mozart, a perfectly played Chopin or Liszt is Artur Rubinstein or Vladimir Horowitz. Klara Haskil, a musician of taste and great skill, played the concertos in F major (K459) and D minor (K466) powerfully, stylishly, and with a noble touch, to the delight of the audience.

Die Weltpresse 27 August 1951

November 1951

He recorded Mozart's Concerto No.15 in B flat major, KV 450, for La Voce del Padrone with Ettore Gracis (with whom he performed approximately 70 concerts over the years).

Recorded on June 26 - 27, 1951 in Milan, Teatro Nuovo.

He performed Mozart's Concertos No.13 in C major, KV 415 and No. 23 in A Major, K. 488 on 15 December, 1951 in Rome - Auditorium di Roma della Rai

- Carlo Maria Giulini conducting RAI Roma Orchestra

First tour of South Africa (November 1951)

? On this tour, there was an incident in a hotel in Port Elizabeth. After helping his tuner with the piano and not changing his clothes, Michelangeli went in to dinner in the luxurious restaurant of his hotel. Management wanted to eject him but he fought physically with them and then sat down, ordered a tremendous dinner with four bottles of the most expensive French wine (which he didn't drink), then paid a huge bill with no tip and left!

See Jan Holcman, "Pianist Without Portfolio" an interview in Bolzano for The Saturday Review, 30 July 1960. Holcman incidentally admits that in his renditions of Chopin he finds ABM to lack the rare fifth dimension.

11 & 15 November 1951: Player Theatre, Johannesburg

Friday 16 November 1951: Durban, City Hall

Sunday 18 November: Plaza-Skouburg (?)

Tuesday 20 November: Opera House Pretoria

Thursday 22 November: Cape Town: 5 Scarlatti sonatas, Bach-Busoni Ciaccona, Beethoven Op.2/3, Chopin.

ABM's tuner Cesare Augusto Tallone focuses in his book (published Milan, 1971; is it the same as Cesare Augusto Tallone, Fede e lavoro: memorie di un accordatore, Rugginenti, Milano 2021?) in particular on the Athens-Khartoum-Johannesburg tour (see his book chapter "Flight to the South"). He makes numerous observations in the chapter "From Travel Notes in South Africa," regarding the natural beauty and misery of South Africa. But this may refer to a tour of South Africa in 1958/59 - see the details there.

1952

Concerts in Great Britain and France. First summer advanced courses in Arezzo (his assistant is Isacco Rinaldi), which continued in 1953 and from 1955 to 1965.

1 February, 1952: Turin, Italy (radio broadcast )

Ravel: Piano Concerto in G major

– Nino Sanzogno / Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI

12 February, 1952: Teatro Petrarca, Arezzo, Italy

Scarlatti: Sonata in A major, K.322, in D major, K.29, in B minor, K.27

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, Op.2 No.3

Chopin: Piano Sonata No.2 in B-flat minor, Op.35

Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales [available on PRAGA Digitals]

Brahms: Variations on a theme by Paganini, Op.35 [edited by Michelangeli]

Valses nobles et sentimentales are a suite of waltzes composed by Maurice Ravel. The title was chosen in homage to Franz Schubert, who had released collections of waltzes in 1823 entitled Valses nobles and Valses sentimentales. The original piano version were published in 1911; an orchestration by the composer was released the following year.

The epigraph at the head of the score, ‘the delightful and ever novel pleasure of a pointless occupation’, suggests that the notes provide their own rationale; but the Henri de Régnier novel from which the quotation comes deals with a young man’s amorous adventures, so, as often with Ravel, there is a tension between strict form and unbounded emotion. In coaching the work, he insisted on the cross rhythms being brought out, and Vlado Perlemuter remembered: ‘I had never seen his eyes so bright—he was so determined on being understood.’ (Roger Nichols)

18 April 1952, Bologna

Scarlatti, 3 sonate; Beethoven, Sonata n. 3 op. 2; Chopin, Sonata op. 35; Ravel, Valses nobles et sentimentales; Brahms, Variazioni su un tema di Paganini.

28 May, 1952: Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, France

Ravel: Piano Concerto in G major

– Igor Markevitch / Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

Everett Helm in Musical America (July 1952) wrote: 'There followed a rarely beautiful work of Malipiero, La Terra, an oratorio for chorus and small orchestra based on the Georgics

of Virgil. This music is anything but revolutionary, but it is also anything but conservative or neo-romantic. It speaks a quiet but profound language in which shock effects—indeed, “effects” of any kind—are rigorously excluded. Malipiero’s melodic gift and his ability to spin a melodic line of great length and beauty are apparent...

Mr. Markevitch did not seem an ideal conductor for this music, for his interpretation lacked poetry and sensitivity. This lack in Mr. Markevitch’s conducting was confirmed in Ravel’s familiar Piano Concerto. The Rome orchestra is not of the highest caliber, but this does not explain the conductor’s insensitivity not only to the poetry and meaning of the music but to the sound of the orchestra. In the Ravel concerto, Arturo Benedetti

Michelangeli played with remarkable accuracy, sang froid, and bravura. The accuracy was praiseworthy; the other two qualities entirely out of place.

31 May/1 June 1952 La Scala Milan

Markevitch - Michelangeli with the Orchestra and Chorus of Santa Cecilia

More unique than rare, at La Scala we heard this evening a programme dedicated to symphonic compositions created within the last 60 years: the oldest composer, of the five programmed, was born in 1865, 87 years ago. The courageous creator of this programme—courageous if we consider how little our audience is a friend of the new—was Igor Markevitch, in his role as conductor, who created it yesterday. It began with Busoni: a Suite of four pieces with interesting incidental music for Gozzi's Turandot: it continued with a Dallapiccola, premiered in Milan: I Canti di prigionia for voices and instruments (to be precise, plucked instruments and percussion - harps, pianos, vibraphone, xylophone, bells, and so on) in which the now twelve-tone Florentine composer elaborates, in admirable counterpoint and in a sort of staccato musical asceticism, the theme of the Gregorian chant Dies irae, a much-used theme of all times.

The first part of the concert ended beautifully with that masterpiece of modern musical literature, Ravel's Concerto in G for Piano and Orchestra. The second initiative was with Kodaly's Psalmus hungaricus, one of those scores that have the defect of becoming clearer with each further listening: it ended with Dukas's charming and effective Apprenti sorcier.

Benedetti Michelangeli magnificently interpreted Ravel's Concerto; he did so with that refined touch and virtuosity we know from him. (Corriere della sera, 1 June)

Lidia Kozubek states (p.65) that the teaching courses took place in Arezzo in summer from 195 2to 1964, and in winter in Bolzano - an Apline village. In 1960-61 Michelangeli also conducted some courses in Moncalieri near Turin, organised by the Fiat company. He aslo lectured at the summer courses of the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena in 1965 and 1966, and at Lugano in Switzerland during 1969-71, these being his last public courses. Bulgarian Olga Shevkenova, who took part in the 1955 Chopin Competition, was a student, as was Remo Remoli, who participated in the same competition in 1960 (as did Camille Budarz). Kozubek also recalls fellow pupils Elias Lopez (Puerto Rico) and Renato Premezzi (USA). She later met Jörg Demus (Austria) and the Czech Ivan Moravec. And during her travels to Japan, she came in contact with Yoko Kono, Moto Sasaki, Akemi Murakami and Shigeru Asano. Paulina O'Connor teaches at the University of Perth.

1953

17 June, 1953: Florence, Italy

Mozart: Piano Concerto No.20 in D minor, K.466

Liszt: Piano Concerto No.1 in E-flat major, S.124

– Dimitri Mitropoulos / Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

ABM played with Karajan again in La Fenice, Venice on 16 September 1953, namely the Ravel concerto on the occasion of the XVI International Festival of Contemporary Music with the Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della Radio Italiana. The programme included two nocturnes by C. Debussy, Ravel's concerto in G minor for piano and orchestra, and the second part featured Debussy's La Mer and Ravel's suite Daphnis et Chloé.

(Corriere della Sera. 23. 9. 1953 + 23-24. 9. 1953)

According to racingsportscars.com, the sole listing for Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli is the 1953 Mille Miglia. Further digging at teamdan.com reveals that Fiat 750 Sports No. 2216 (i.e., leaving Brescia at 10:16 p.m.) ended up 258th of 283 finishers. Scads of others either failed to complete or even begin the 1000 miles. This Fiat was driven by Pier Luigi Patti with Giovanni Rocco as co-driver. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and Farisoglio are listed as part of the entry, though not participating in the race meeting. (Dennis Simanaitis)

25 December, 1953 in Turin - RAI Studios

Franck / Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra in F-Sharp Minor, M. 46

- Mario Rossi conducting Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI. LISTEN

In 1953 he recorded two of Mozart’s Piano Concertos with conductor Franco Caracciolo (No. 13 in C major K. 415 and No.23 in A major K. 488)

Orchestra Alessandro Scarlatti: November 23 - 24 & 27 - 28, 1953 in Naples - Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella

1954

Sick with tuberculosis, ABM completely suspended his concert activity. Diario de Noticias (Rio de Janeiro, 6 March 1954) had announced that he would be playing for the Associação Brasileira de Concertos in July. Presumably this was cancelled. Even earlier, in Jornal do Brasil 24 February, Renzo Massarani has said 'we are doing everything possible to bring Benedetti Michelangeli to perform at the fourth centenary of São Paulo celebrations.'

A Muda Cena (April) - the first Brazilian magazine focused on film-related topics - had announced: 'Italian pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli will come to Brazil, contracted by ABC, where he will give recitals in Rio and São Paulo. The young and talented concert pianist will be in Rio during the month of July.'

Two piano recital had been advertised for Salzburg: on July 28 and 31, 1954 at the Mozarteum with pianists Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli (Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Paganini, Ravel, Scarlatti) and Hungarian Gézà Anda (Beethoven, Brahms, Bartók, Mozart).

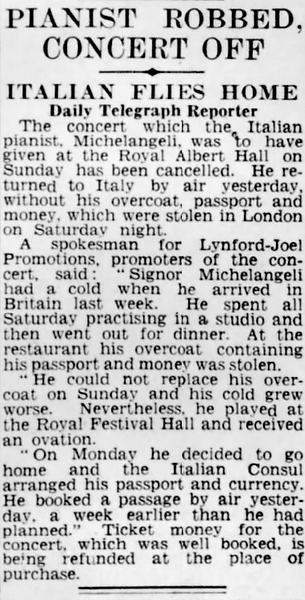

Daily Telegraph, 8 October 1952

The divine jester of the piano

Dubious inventions, and even pranks, are a way of evading and disappearing. But a different way from the solemn one of the Genius of Romanticism. One almost gets the feeling that, in many cases, looking closely at facts and contradictions, Michelangeli's Genius was contaminated by the jester (il Genio si contaminasse col giullare), in the classical sense of the word. Like the Greek rhapsodists, like medieval jesters, like Provençal troubadours, like Shakespeare's fool, like François Villon's "bon follastre." Like the "trickster" of European anthropological literature.

A performer, a "trickster"/ imbroglione (in inverted commas), a popular wandering artist, capable of enchanting with prodigies and magic and then disappearing. A cross between a criminal and a saint. Michelangeli, once questioned in court about his profession, replied: "a street musician (suonatore ambulante)" He seemed fully aware—if not literally, then in spirit—of a famous saying of the Desert Fathers: "In many cases, you have to act crazy." Being strange to avoid giving yourself to the world. Being strange—ungraspable. Disappearing and lying to protect something deeper. Something sacred.

Many of those who knew him personally sensed Michelangeli's underlying fragility, and often took a protective attitude toward him. For example, much remains uncertain about his love life. Michelangeli married early, to Giulia Linda Guidetti, whom he had met at a very young age, and he never divorced. Relatively little was known about his (presumably numerous) adventures, aside from a page in Marisa Bruni Tedeschi's book, where she humorously confessed a liaison with the Maestro. Everyone else maintained a discreet attitude, seemingly stemming from a sense of protectiveness.

For Marisa Bruni Tedeschi, see this section of the website

Bruno Giurato (April 2018)