Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

1970s

« Übermensch am Steinway »

In the 1970s Michelangeli lived in Switzerland and refused to live or perform in his native Italy for over a decade. On 23 July, 1970 his mother, Angela (known as Lina) Paparoni, died.

Following ABM's divorce from Giulia Linda Guidetti (whom he had married in September 1943 ), his secretary - and later his agent and partner - Marie-José Gros-Dubois (20 years younger than he) organised concerts and dates for him, and also presided over his financial affairs.

'He taught in Lugano in 1969, 1970, and 1971. In the following years, he only gave lessons occasionally to a few students. Walter Klien, Jörg Demus, Martha Argerich, and Maurizio Pollini (these last two c.1960) are the best known of the many young pianists who benefited from his advice, but it cannot be said that his teaching created a true "school"'. (Piero Rattalino)

From 1969 to 1971, the Villa Heleneum hosted a piano school run by ABM and composers Carlo Florindo Semini and Franco Ferrara. Built between 1930 and 1934 on the site of the former Villa Caréol, Villa Heleneum is an emblematic place in Lugano that has hosted various activities combining art, research, and outreach throughout its history. Located on the shores of Lake Lugano, both Swiss and Italian, Villa Heleneum is a place of cultural and linguistic confluence between the north and south of the Alps. More than a strategic location, Villa Heleneum is a fully anchored in its surrounding natural environment. Every floor and every viewpoint of the Villa opens onto Lake Lugano and its breathtaking horizon over the mountainous peaks such as Monte San Salvatore, Monte Generoso, and Monte San Giorgio. The Villa Heleneum is set in a public garden full of Mediterranean harmony where different trees (such as cedars, cypresses, eucalyptus) and plants (from palm trees to ferns, camellias, glycines and roses) are mixed on an architectural promenade. Website

"If I've understood correctly, the question is "Why do I teach?" I've been performing concerts for 30 years but I've been teaching for 35 years. I started to teach because I was asked. It's not a vice or a mania. On the contrary: I've made great sacrifices to divide time in a proper way between concerts and teaching. It's always been a great concern of mine."

ABM was filmed in Toronto for CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) TV Studios, 24 February 1970 playing Beethoven's third Sonata.

A Washington DC recital of 5 March 1970 was described as 'a true revelation, and certainly one of the most remarkable recitals I have heard in a full lifetime of concert-going.' Beethoven No.32 Op.111 emanated such 'transcendental loveliness' that this critic could recall only one other live performance, by Artur Schnabel, that had moved him so deeply.

The Beethovenfest in Bonn in 1970 celebrated the bicentennial of Ludwig van Beethoven's birth.

Wednesday 6 May, 1970, Beethovenhalle, Bonn, West Germany. Sonate op. 26 As-dur

(mit dem Trauermarsch); Sonate op. 27/2 cis-moll (Mondschein); 11 Bagatellen op. 119

Sonate op. 111 c-moll .

10 June 1970, Grosser Tonhallesaall, Zürich (aslo 20th?)

The Zürcher Kammerorchester's first June Festival concert (conducted by Edmond de Stoutz) was once again marked by the artistic imprint of an outstanding pianist. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli played Mozart's Piano Concerto in C major, K. 503. He lifted the work into a luminous world of sonic magic and revealed all the hidden beauties and messages of this piano concerto, which have never been written down more wittily, intimately, and movingly. "Musicians are often praised for transporting the audience to almost heavenly realms." * Certainly, Benedetti Michelangeli can also be praised for this achievement. But this only partially does justice to his artistic talent. It must also be mentioned that all human emotions are sublimated in his playing: a serious joy of life, a cheerful awareness of our own fragility, the coquettish sensitivity of the Rococo which one could almost regard as a personal intrigue against the subconscious, and the exciting tension which demands expression and movement in every consciously lived life.

Man wird seinem künstlerischen Vermögen aber damit nur zum Teil gerecht . Erwähnen muss man nämlich noch , dass in seinem Spiel alle menschlichen Gefühle sublimiert vorhanden sind : eine ernste Lebensfreude , ein heiteres Wissen um die Zerbrechlichkeit , die kokette Empfindsamkeit des Rokokos , die man beinahe als persönliche Intrige gegen das Unterbewusstsein betrachten könnte , und dio erregende Spannung , welche in jedem bewusst gelebten Leben nach Ausdruck und Bewegung verlangt.

Die Tat, 13 June 1970

11 October, 1970: Bonn, West Germany: Beethoven 200th Anniversary Concert.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, Op.2 No.3; No.4 in E-flat major, Op.7;

No.32 in C minor, Op.111

Encore: Beethoven: Bagatelle in D major, Op.119 No.3

Friday, 23 October 1970, Zeneakadémia, Budapest, Hungary. Beethoven, Sonatas Nos.4 in E flat Op. 7 and 32 in C minor Op.111; Chopin, Scherzo in B flat minor, Ballade in G minor, Polonaise Brillante in E flat.

Festival de La Grange de Meslay, Tours, France, July 1970. This festival was founded by Sviatoslav Richter.

Mya Tannenbaum wrote: TOURS. At first it was love at first sight: a magical integration between character and landscape. Sviatoslav Richter, the most famous Soviet pianist, had allowed himself to be photographed in the meadows. The Russian in the foreground, surrounded by ears of corn; the Russian in profile, with the purple local wines in the background. "My festival will be born here," he said, "in Touraine."

From that moment on, Pierre Boille, the architect who loved the crumbling medieval walls of the old city, the man who inspired sentiments of preservation in the inhabitants of the oldest neighbourhoods (a new desire to restore body and soul to the leprous stones), decided to find the perfect venue for Richter's festival. Stuck in his restoration project, Boille envisioned an ancient hall, yes, but untouched by history. He visited the priory of St. Cosme and ruled it out. There was the 9th-century church, founded by the Canons Regular of St. Martin of Tours, demolished during the Revolution; and then the immense refectory, damaged but safe. The reading corner remained intact: a sort of (musical) podium in pure Romanesque style. But there were also the eight years of the heretic Bérenger, the last twenty of the poet Ronsard, spent in the prior's cottage: a crowd of ghosts, which Richter could not have erased. He visited the Renaissance castle of Azay-le-Rideau: engraved, painted, sculpted everywhere, the salamander of Francis I. Excluded. He visited the sixteenth-century palace of Saché; Balzac lived and worked there, for a long time. Balzac plus Richter, excluded. He visited the triumphant castle of Chenonceaux; but Henry II, Diane de Poitiers, Catherine de' Medici, Henry IV, Voltaire, Rousseau quickly chased him away. Excluded. Finally, he happened upon Meslay, an old farmhouse built in 1220 by the Marmoutier friars. The barn, 60 metres long and 25 metres wide, supported by high oak beams that divide it into five naves, resembled a church. The acoustics proved perfect. So, in 1964, the owner of Meslay sold the farm to Richter for a few days. The barn was transformed into a concert hall, preserving intact its delightful imperfections, its rural happiness, the age-old scent of hay, and even the rigour of a Romanesque line. Six days of music, and gone were the piled grass, the hoes, the sharp sickles, the supplies of fodder, and the swallows' nests.

The Festival of 1970, spread over two weekends, opened with the Warsaw Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra: 16 very young soloists, united by the authoritative presence of first violinist Karol Teutsch and an extraordinary sense of rhythm. The next day, the Ensemble vocal et instrumental de Lausanne, conducted by Michel Corboz, performed Claudio Monteverdi's "Orfeo".

The large audience, gathered in the barn from Washington, New York, Berlin, Prague, Rome, London, Geneva, and Paris, witnessed a curious scene. Sviatoslav Richter, seated in the front row, listened raptly; at the piano, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli attacked, caressed, cajoled, and transfigured Beethoven's sonatas. The rain beat down heavily on the building's ancient tiles, heightening the enchantment. At the end, Richter commented : "It wasn't a concert, but a monument to Beethoven; none of us pianists will ever reach Michelangeli's level . On Saturday, the timeless Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. On Sunday, the Festival's star performer: Richter. And the singular character who fears boredom more than imperfection, struck the right note with Beethoven's 33 Variations on a Diabelli Waltz.

Source: Corrado Grandis (2016)

Sviatoslav Richter's diary entry (Bruno Monsaingeon, 2002)

« Übermensch am Steinway »

Freiburger Nachrichten, 13 June 1995

‘There is no other artist in the wide world of pianists who makes things so difficult for himself for the sake of pure beauty,’ wrote Joachim Kaiser about him. He is said to have practised Beethoven's Sonata No. 32 Opus 111 until the birds outside his house were whistling along with him.

Arnaldo Lenghi remembers...

In an interview with journalist Renzo Allegri (source unknown), Dr Arnaldo Lenghi, a friend of the pianist made this point:

'He's someone who strives for perfection. He doesn't play when, for various reasons, he fears he won't be able to achieve it. He's never canceled a concert for personal reasons. He played while his father was dying. I've even seen him play with a broken back. It was in 1970, the bicentenary of Beethoven's birth. Major events were organised in Bonn, and he was entrusted with the opening concert. In March of that year, the maestro was in a car accident. He slipped on the icy road and ended up in a ditch. He appeared to have only minor bruises. He managed to continue his journey and reach Rabbi. He had even resumed studying, but after a few hours, he felt severe back pain, so much so that he was forced to interrupt his studies and try to reach his bedroom. While passing from the cabin where he keeps his piano to the one where he sleeps, he fell into the snow. With great effort, he dragged himself to his room. He remained nailed to the bed all night, unable to move.

'In the morning, he called me, begging me to come to him. I found him in a pitiful state. Even the slightest movement caused him terrible pain. I loaded him into the car and drove him to Bergamo. X-rays revealed that he had fractured two vertebrae. He needed to be hospitalised, but he refused. I found some specialist friends who came to treat him at home. We put him in a cast. He was thinking only of the Bonn concert and kept asking to be able to play. After a week, we were forced to remove the cast and construct a special brace that allowed him to sit at the piano. I had an upright piano brought into his room, and he started playing again. I remember there was a particularly difficult passage of a few notes: one day I heard him repeat those few bars for over three hours. He stayed at my house for a month. During all that time, I never heard him complain about the pain, not even during the first few days, when it must have been excruciating. He never even asked me for an aspirin. When he went to Bonn, he wasn't healed, but he wanted to play, and it was a triumph.'

1971

'What is surprising is not so much the number of concerts he performed in the second half of his career— Horowitz, in his entire life, played fewer than half of them—but the loss of the intellectual curiosity and lively spirit of cultural initiative that was evident in Benedetti Michelangeli in the 1950s. We know that in the 1960s, he studied Tchaikovsky's Concerto Op. 23 and Dvorák's Concerto, which he never performed in public. He did not

even expand his Mozart repertoire, on the occasion of the bicentenary of Mozart's death [1991]. After the age of thirty-five [1955], Benedetti Michelangeli re-studies the part of his repertoire that he decides not to abandon. ' (Piero Rattalino)

Wednesday 24 February 1971, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland

More than thirty years have passed since Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, then 19 years old, first came to La Chaux-de-Fonds, armed with the First Prize at the Geneva International Competition. Over the years, he has risen to the height of his career and fame. His appearance is each time an event and brings crowds of music lovers flocking: in Warsaw, in 1949, when he was called upon to play on the centenary of Chopin's death; in Salzburg, in 1965, where he was acclaimed by an audience of pianists who recognized him as a master. It is this prince of the keyboard that we will have the pleasure of hearing on Wednesday, February 24, at the Salle de Musique, as part of the tenth subscription concert. Beethoven and Debussy share the programme: from the former, two classical sonatas, and from the latter, Children's Corner, a suite of short pieces with evocative titles—which Debussy dedicated to his daughter Chouchou—and two series of Images for piano, which are like sketches with changing reflections. The composer of the "Ninth" and the composer of "Pelleas" have in common that they renewed the pianistic style. However, they are two worlds, two eras, two languages, contrasts that give this program a particular appeal, in keeping with the transcendent qualities of the performer. (L'impartial, 23 February 1971)

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in Winterthur: Magier aus dem Elfenbeinturm (Musician from the Ivory Tower)

In a special concert organised by the Musikkollegium Winterthur, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli gave a piano recital on February 27th in the Stadthaussaal. The certainly not small hall was completely sold out; the concert ended with thunderous applause. Benedetti Michelangeli is, indeed, a unique musician. He affords himself (and is entitled to do so) to make no concessions to the audience regarding the programme. Although he included two Beethoven sonatas, they were none of the famous, "great," widely heard works, but rather works from his youth: the C major Sonata Op. 2 No. 3 from 1795 and the E-flat major Sonata Op. 7 from 1796/97. And in the second half, he played works by Debussy that weren't particularly concerned with outward impact: the charming, if at times somewhat brittle, movements of "Children's Corner" and "Images" (I and II). This, one could say, is the programme of someone who is aware of his irresistible appeal. And this time, too, it presented itself: complete fascination with an art of touch, with a highly differentiated playing culture that masters even the finest nuances, that possesses power but also the possibilities of almost ethereal sounds ("Reflets dans l'eau"!), with a pianistic technique that understands how to grasp the most difficult things as something completely self-evident and natural, with a musical interpretation (which is much more a complete penetration) that knows no pose, that with the assurance of good taste and profound knowledge of style imposes even peculiar, idiosyncratic interpretations (for example on Beethoven's rhythm) on the listener and that simply dispels even the slightest reservations or does not allow them to arise at all. It even encompasses musical humor: we have never heard «Golliwog’s Cakewalk» funnier, fresher, and more cheerful... The highest artistic sensitivity is combined in this music with fresh spontaneity; it never releases the listener from the spell it casts over them for a second.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 3 March 1971

10 [?] March, 1971: Salle Pleyel, Paris, France

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, Op.2 No.3; No.4 in E-flat major, Op.7

Debussy: Children’s Corner (Suite); Images (Book I & II)

Encore: Chopin: Waltz in E minor, Op.posth (B.56)

Jacques Lonchampt in Le Monde (19.3.71):

True to his appointment—unfaithful to his legend—Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli came to give an admirable recital at Pleyel, where the entire Parisian piano world was waiting for him. He entered slowly, silently, without a smile, a shadow on his aristocratic face as if wounded by melancholy.

With this adored and distant pianist, nothing is given to effect. This superb pianistic talent, the finest one could wish for, is neither cuddly nor complicit. [Ce superbe talent pianistique, le plus beau qu'on puisse souhaiter, n'est ni câlin ni complice] A simplicity without feverishness, a freedom unbound by all constraints as if it had never known them, the natural radiance of a sound without softness or hardness, of an infallible instinct.

If he plays two early Beethoven sonatas (the 3rd in C major and the 4th in E-flat), it's probably one too many, for we tire of these contrived formulas, of this rhetoric of transitions that enclose beautiful flashes of poetry and sentiment in a somewhat showy structure. But Benedetti Michelangeli erases awkwardness and grandiloquence, emphasizes the almost Schubertian gentleness or youthful brilliance, and gives this still somewhat tangled lyricism a richness of substance and a chivalrous elegance that is sometimes miraculous.

With Debussy, he penetrates to the most intimate part of his art. The clean line, filled with light, suddenly blurs into shimmering depths, the Serenade to the Doll unfolds in a child's sleep, your Snow dances in silent flakes; but the very traces of reality are erased in the two notebooks. of Images, where all that remains is the paradise of sound, the inner movement that combines the most delicate rubato with rhythmic accuracy, dreamy nonchalance with architectural splendor. An art that undoubtedly does not go beyond sonic voluptuousness, but, in its depths, borders on ecstasy. [Un art qui ne va sans doute pas au-delà de la volupté sonore, mais, dans les profondeurs de celle-ci, confine à l'extase]

Prague Spring

'It is the 50th anniversary of the year that the Communist party was formed in this beautiful, sad city, and nobody is allowed to forget it. Red banners with the numerals 50 hang all over. Display windows have the figures as part of their design. Party meetings are in progress, and a very big congress is scheduled for next week. Perhaps the Government made a special gesture toward national pride in its programming for the Prague Spring. It offers a once‐in‐a-lifetime chance to sample, on consecutive nights, the classics of the Czechoslovak repertory. Of Smetana there are “Libuse,” “Hubicka” and, of course, “The Bartered Bride.” Dvorak is represented by “The Jacobin,” “Rusalka” and “The Devil and Kate.” There are no fewer than five Janaček operas.'

(Harold Schonberg, The New York Times , 18.5.71)

Thursday, 20 May 1971, Municipal House – Smetana Hall, Prague

Mozart : Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 20 in D minor, KV 466

Gustav Mahler : Píseň o zemi /Das Lied von der Erde (Vera Soukupova & William Prybyl)

Czech Philharmonic & Vaclav Neumann

Monday, 24 May, 1971, Rudolfinum – Dvořák Hall, Prague

Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonata in C major, Op. 2 No. 3; Sonata in E flat major, Op. 7

Claude Debussy: Children's corner, Images

When it was announced in the preliminary programme of the Prague Spring that Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli would be coming, tickets for at least two Smetana Halls and four Artists' Houses could have sold out within a few days. Such was the impression he left in Prague eleven years ago.

He took his Petrof grand piano with him on a tour of South Africa. When the piano returned to Genoa after a few months, the Master was surprised that the instrument had kept its tuning in the harsh conditions below deck. He also remembers the Easter concert in the Vatican before Pope John XXIII, where he played the Petrof grand piano. Here in Prague, he naturally also played the Petrof grand piano. And then the instrument was sent to Yugoslavia, where he gave concerts on 4 and 8 June 4 in Zagreb (now Croatia) and on 11 June in Belgrade (Serbia).

He has a Jaguar and loves high speeds. He maintains a strict diet, does not eat fatty meat, his favourite drink is red wine, he admires Chinese cuisine [I think the author may mean Japanese] and loves to cook. In European hotels, he demands a suite with a kitchenette. He promised to return to Prague early next year because he considers the Czech Philharmonic to be one of the best orchestras in the world and he enjoyed working with Václav Neumann. He appreciates the Prague audience, who do not go to concerts to see him, but to hear him!

Svět v Obrazech 19.6.71

'And so, Michelangeli's first concert performance this year already provided a lot of food for thought, offering a tempting comparison with Sviatoslav Richter as his stylistic counterpart. Isn't Richter an unpredictable element, a predatory river that takes with it even its limiting banks, never mind building no dams for itself? And isn't Michelangelo, on the other hand, the sum of rational discipline that achieves maximum beauty through harmonised and balanced proportions and proportionality of contrasts, their inconspicuous, but all the more surprisingly effective confrontation? Isn't Michelangeli the "heir" of neoclassicism and Richter the "heir" of expressionism?

But Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli surprised the people of Prague for the second time this year in his recital (24 May) and greatly problematised such ideas. Many listeners were very surprised, some even shocked, by his interpretation of the young, still “Haydnist” Beethoven sonatas (C major, Op. 2, No. 3; E flat major, Op. 17). It is true that in some respects the “neoclassical” approach was still maintained: flat dynamics in the manner of registration, again heightened by a color-differentiated stroke when leading the voices, and moderation in the choice of contrasting tempos. The fact that Michelangeli never drags out slow tempos too much is directly a condition of his colour-stroke technique, which requires moderate and sometimes completely minimal pedalling, in order for the richly nuanced scale from his flowing legatissimo to the sharpest staccatissimo to sound well. At tempos that are too slow, moderate pedalling would create a sonic void, thus disrupting the context of the semantic connections of the musical fabric; at tempos that are too fast, our ear would not be able to perceive the richness of the differentiated touch.

Dramaturgically, the choice of both sonatas as a counterpart to the second, Debussy-esque half of the evening cannot be disapproved of, because both sonatas contain much of the already quite modern sonic magic (especially the free movement in C major of the sonata and the trio part of the scherzo in E flat major of the sonata). However, it seems that Michelangeli heard this sonic quality with ears that were already too impressionistic, because Beethoven himself certainly could not have dreamed of the sonic refinement he used. However, he surprised his listeners even more with the breadth of his dynamic palette, which was completely unheard of in him up to that point...

The performance of Debussy's Children's Corner and all six compositions (the first composition of the second series: "Cloches à travers les feuilles" was mistakenly omitted in the printed programme) of the cycle Images was, as one might expect, absolutely sovereign. (...). The richness, diversity and variability of the touch that the Italian master demonstrated here are not immediately heard: for example, the sound "caresses" of portamento octaves (Reflections in the Water), sound timbres and "timbre polyphony" (Bells penetrating the foliage), the "silky silvery" pianissimo stroke (A moon descends on the former temple), etc.

But even in Debussy, Michelangeli surprised in places. For example, in the fourth movement of the Children's Corner (The Snow Dances), the music suddenly flashed with a violent dramatic outburst, almost Janáček-like! There is no doubt that the great piano art of the Italian master has changed stylistically from how we knew it before. The artist, who had previously been so reserved in his expression, began to burst forth with hidden inner energy more than once. This was expressed in an interesting and visually external way in a kind of quasi-conductor-like, purely mimic integration of the metrical-rhythmic movement with additional gestures after the keys were sounded, which in an artist of such an unostentatious performance cannot be a conscious play for effect, but rather a spontaneous expression of the necessary discharge of accumulated energy.

Well, Michelangeli surprised the Prague musical public with his hitherto unknown power and ability to seek contrasts and revive for the listener "old" music. In some cases, he did so with complete disregard for established and established stylistic norms, which certainly shocked some listeners. But no one can deny his powerful, enlivening creative power, because the listeners were filled with vivid and exciting impressions long after the final chord of his recital had sounded.

JAROSLAV JIRÁNEK, Hudební Rozhledy, 1971 (XXIV/1-12)1971 / No. 7

Zagreb

Zvonimir Berković, Hrvatski tjednik (25 June 1971) wrote of a recital at the Hrvatski Glazbeni Zavod (Croatian Musical Institute), Zagreb on ?4 & 8 June: 'In his childhood, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (by his own admission) did not like the piano. In fact, he hated it with a passion: the very sound of that instrument aroused his rage and brought him to the brink of hysteria. It was as if even then, poor thing, he had a presentiment that in the narrow space of the keyboard a lifelong battle would be fought for himself and that there, and there only, his fate would be decided. He knew instinctively that that huge bird's wing above the piano did not rise to fly, but to close with a clang and trap anyone who tried to penetrate the last secrets of the black music box. What Maurois wrote about the young Proust could be applied to the case of little Benedetti: he knew well that he had a gift, but he had a presentiment that the day when he would really set to work on the only work for which he was created, he would give his life to that work, and he instinctively retreated from that sacrifice.

On je skladni demon, razbarušeni perfekcionist, buntovni tradicionalist, on je vedri mračnik. snažni mekušac, najnormalniji osoban destruktivni graditelj.

ABM is a harmonious demon. a disheveled perfectionist, a rebellious traditionalist, he is a cheerful dark one. a strong softie, the most normal eccentric. a destructive builder, a rational mystic, he has touched all extremes with his fingers, he has opened himself to all unrest and, without calming them, has made peace between them. In short, his playing today is the pianistic Absolute. Since he vividly remembers the price at which

paid for his victory and since he knows how fragile perfections are built on the vibrations of air, he does not accept any surprises on the podium, even pleasant ones.

On se ne može povjeriti glazbalu, kojemu ne poznaje dušu is kojim nije postigao sporazum o kraju-njemu u pitanjima pa čak ako ako je taj instrument objektivno bolji, zvučniji i podatljiviji od onog prilično plehnato-zvučnog Petrofa koji je iz nekih čudnih (vjerojatno neglazbenih razloga) zamijenio njegovog nekadašnjeg vjerodostojnog pratioca, plemenitog Steinwaya.

He cannot trust an instrument whose soul he does not know and with which he has not reached an agreement on the ultimate issues, even if that instrument is objectively better, more sonorous and more pliable than that rather pleasant-sounding Petrof which for some strange (probably non-musical) reasons replaced his former faithful companion, the noble Steinway.

[His] ear must be ready to signal at any moment if the balance between vision and realisation, copy and original, is disturbed. The other evening, in the hall of the Croatian Music Institute, we witnessed one such moment of alarm. While playing Debussy (Images), a chord did not sound exactly as predicted by Michelangeli's strict script and he, without thinking, automatically repeated that chord. In the diffused form of Debussy's impressionistic paintings, no one in the hall (except for the rare pianist enthusiasts who followed the entire programme from the score) noticed this outrageous audacity and challenge to concert etiquette.

Michelangeli is also known in the world as an artist who cancels concerts at the last minute, who drives record company owners to despair; he is known to sullenly avoid public places and public people. In general, he has given plenty of reason to be considered an eccentric. To some, he is a magician of the new pianism, a romantic of cold sensitivity, while others consider him an affected boaster, an actor who fascinates unstable listeners with the pallor and stiffness of his facial expression, contemptuously indifferent behavior on the stage, thus playing some semi-metaphysical being, etc. However, we have no reason to doubt the sincerity of his own statements when he speaks of himself as a man who wants to be nothing more than a faithful performer of musical works, a perfect

a skilled craftsman, an objective (in the almost scientific sense of objectivity) researcher of musical values.

And for this concert occasion, the pianist Benedetti Michelangeli dug up two of Beethoven's sonatas (in C major, Op. 2/3 and in E flat major, Op. 7), which, as early works - as Marx would say, are rarely found in the repertoire of virtuosos. But while preparing these works, he could not forget the vast experience of his pianism; achieving the perfection of his performance, he could not resist the urge to perfect Beethoven a little.

U tim mladenačkim stvarima Michelangeli je lako našao zamet-ke ideje iz kojih su kasnije nastali čitavi glazbeni pokreti; njegovi spretni prsti brzo su napipali tempirane bombe, paklene strojeve koje je Beethoven brižljivo skrivao među notama i osta-vljao ih ih neispaljene neispalje jer još nije bilo vremena da prva njegova eksplozija protrese povijest glazbe.

In these youthful works, Michelangeli easily found the germs of ideas from which entire musical movements later emerged; his deft fingers quickly felt the time bombs, the infernal machines that Beethoven carefully hid among the notes and left unfired because it was not yet time for his first explosion to shake the history of music.

Michelangeli's pianistic-pyrotechnic passion found a way to activate these dangerous devices, and before us those two sonatas flared up like the Appassionata, like symphonies. And what's more, from that flame suddenly emerged the whole of Schubert, Schumann and everything that had been fed by Beethoven for a century and tempered by Beethoven.

Of course, there was a danger that this belated explosion would not blow up something without which there is no young Beethoven: a warm naivety and a robust mental health. In his own bizarre way, Michelangeli took care of this: in the fullness of his exuberant interpretation, Beethoven became even healthier sick than healthy. [?The Croatain seems to be saying the young Beethoven still came through in the performance]

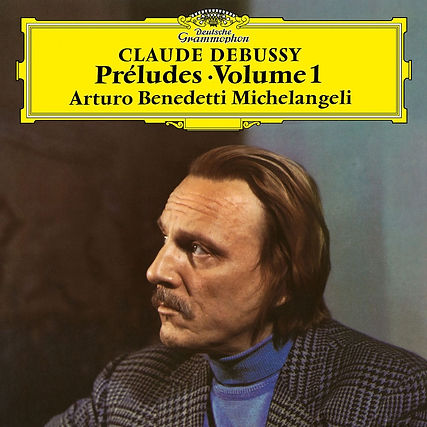

Deutsche Grammophon

June/July, 1971

First contract with Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft. He records works by Debussy (Images I & II and Children's Corner) Beethoven (Sonata no. 4, Op. 7) and Chopin. The Préludes Book I will come later in the decade, in 1978.

25-30 July, 1971: Akademie der Wissenschaften (Plenarsaal), Munich, West Germany

Debussy: Children’s Corner (Suite); Images (Book I & II)

'Michelangeli was capable of a transcendental virtuosity, not always noticed, that had nothing to do with playing fast and loud and everything to do with refinement, and it is well in place(...) especially in the first two Images of the Second Book; also, less expectedly, in “The snow is dancing” from Children’s Corner. The clarity of texture and the laser-like delineation can sometimes be disconcerting if you’re accustomed to a softer, more ethereal style, but they have a way of making Debussy’s modernism apparent and, to my ears, thrilling. He sounds here as if he has had nothing to do with the nineteenth century...

'His Debussy is at once strongly atmospheric and crystal clear. There used to be, and I daresay still is, an either/or attitude to Debussy interpretation: either evocative, 'impressionist' and sensuous, served as it were on a bed of Monet's water-lilies, or cool, intellectual, classical. The truth, surely, is not wholly in either camp. Michelangeli first and foremost affirms that this music deserves and demands the firmest musical definition; therein, I think, is his excellence. He treats nothing as mere 'texture', nothing as a peg on which to hang 'pianism', nothing as a mere pattern of notes to be thrown into the melting-pot of 'effect'. he seems to have discovered the logical, musical place and weight for every note, and the result is the strongest, most colourful, most musical and most poetic Debussy you have ever heard from a pianist.'

(Stephen Plaistow)

Alex Ross in The New Yorker, 22 October 2018: 'Michelangeli’s recording of “Images,” made in 1971, is rightly regarded as one of the greatest piano records ever made. “Reflets dans l'eau” begins with eight bars confined to the key of D-flat major, or, more precisely, to the scale associated with that key. Chords drawn from those seven notes lounge indolently across the keyboard. In the ninth bar, though, the work goes gorgeously haywire. Extraneous notes invade the inner voices, even as a D-flattish upper line is maintained. Pinprick dissonances disrupt the sense of a tonal center, and the music collapses into harmonic limbo, in the form of a rolled chord of fourths. This is Debussyan atonality, which predates Schoenberg’s and is very different in spirit: not a lunge into the unknown but a walk on the wild side. We stroll back home with a descending string of chords that defy brief description: sevenths of various kinds, diminished sevenths, dominant sevenths, and what, in jazz, is called the minor major seventh. Michelangeli, who admired the jazz pianist Bill Evans and was admired by Evans in turn, plays this whole stretch of music as if he were hunched over a piano in a smoke-filled club, at one in the morning, sometime during the Eisenhower Administration. Two bars later, we are back in D-flat—an even more restricted version of it, on the ancient pentatonic scale. Some kind of bending of the musical space-time continuum has occurred, and we are only sixteen bars in.'

1-2 August, 1971: Residenz (Plenarsaal), Munich, West Germany

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.4 in E-flat major, Op.7

This was an LP of barely 30 minutes. 'Only Herbert von Karajan and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau could sometimes afford such disdain for the public.' [Cord Garben, who analyses in detail p.37ff.]

'The last two movements of the Sonata, played with grace, charm, freshness, variety of character, and with what I can only call a quiet relish, are admirable; but in the opening Allegro molto e con brio and the Largo, con gran' espressione there is a lack of emotional commitment, of warmth. These movements seem to me nowhere near passionate enough. The character of the first, at least as I see it, is particularly underplayed. By ignoring the qualifications Beethoven attached to the Allegro marking, Michelangeli deprives it of a lot of its urgency, and of that peculiar, emotionally "pressing" quality it seems to me to have. I cannot find myself convinced by such a gentle pace and very cool delineation of such ardent music, brilliantly "orchestrated" though the playing is. Beethoven didn't write con gran' espressione over all his slow movements, and when he did, I think he wanted to convey something definite. I think he wanted the interpreter to draw us right inside them with playing of exceptional intensity. Michelangeli leaves me on the outside, looking in.' (Stephen Plaistow, Gramophone 12/71)

October & November 1971: Akademie der Wissenschaften (Plenarsaal), Munich, West Germany (13 - 18, 24 - 25, 27 - 29 October & 6 - 8 November)

Chopin: Mazurkas (selection); Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op.45; Ballade No.1 in G minor, Op.23; Scherzo No.2 in B-flat minor, Op.31

Mazurkas

Wilhelm von Lenz: Chopin was truly an incomparably singular phenomenon of his profession, a Pole (Sarmatian) with a French education, French customs,

with the strengths and weaknesses of both tendencies.

Lacking physical strength, Chopin concentrated entirely on the singable style, on relationships and connections, on detail. He was therefore a pastellist "like no one had ever been before." (Chopin's Mazurkas are the diary of his soul's journeys into the political and social sphere of the Sarmatian dream world!). His performance was at home there; Chopin's originality as a pianist dwelt there. He represented Poland, his dreamland, in the Paris salon, which in the time of Louis-Philippe, from his point of view, could be considered an influential political power. Chopin was the only political pianist. He offered Poland, he composed Poland.

ABM's interpretation seems to come very close to this characterization. Even in his playing, we hear both the "dreamland" of the Paris salon, pushed to the limits of decadence and languor, and the brutal, combative spirit of revolutionary Poland in the 1830s. At the time, all of Europe was suffering under the influence of "Young Poland": a wave of sympathy united the rest of the world in the fight for freedom, which would soon be replicated in German territories.

ABM manages to interpret the almost infinite range of mazurkas, from the softly feminine to the rustic peasant dance. In just a few bars, as the formal structure dictates, he shifts with great stylistic sensitivity from one extreme to the other,

without ever losing inspiration. [Cord Garben 43f.]

The ever gracious and perceptive Joan Chissell reviewed the LP in Gramophone June 1972, putting on the disc with some trepidation. 'Would he be aloof and calculating? Or might he thaw? The phrasing is so malleable and the playing so responsive to the mood of the moment that I found it hard to believe this really was imperious Michelangeli. You sometimes almost feel that you might be listening to Chopin himself improvising. The B-flat minor scherzo, surprised me more than anything else in the recital. I thought it was so familiar by now that no one could ever hope to hear it with new ears. It is a tonic to hear each mazurka given such potent character without rhythmic idiosyncrasy or (worse still) whimsy. I'm glad he has unearthed an edition of Op.68/4 in F minor with the once missing middle section reinstated. This was Chopin's last composition of all, written in acute awareness of life's transience: you can guess as much from Michelangeli's intimately inflected phrasing.'

In Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli as I Knew Him, Lidia Kozubek claims that ABM saw Chopin's Mazurkas 'more perhaps in the style of Tyrolese dances from his native Alpine climes, but what a wealth of moods and impressions they contain! Discussing Michelangeli's Chopin album (for DG), Władysław Malinowski (Rocznik Chopinowksi [Chopin Yearbook] Νο. 17, 1985) is said to have found in the Mazurkas that all of Michelangeli's characteristics are to be found to an even greater degree than elsewhere.

"The last Mazurka, in B minor, which closes opus 33 [and one which ABM played many times] is one of Chopin’s great wonders. In it, we hear a synthesis of the heard and remembered with the personally experienced and profoundly true. Lyrical contemplation and dialogue, eruptions of passion, rocking and calming. ‘Where did Chopin hear and catch red-handed the plaintively graceful melodies of kujawiaks, the fiery rhythms of the mazur and the dizzy arabesques of the oberek?’ asked Stefan Kisielewski semi-rhetorically in his beautiful essay on Chopin, written in 1957. ‘How did he transport them out of Poland’, he went on to ask, ‘like that symbolic clod of native soil? How did he preserve them, not eroded, not sullied, on the market of the world – in faraway Paris? It is a mystery, just as the extraordinary unity of his musical personality, made up of so many contradictions, is a mystery. But let us allow Chopin’, concludes Kisielewski, ‘a few mysteries, let us not try to account for everything’."

Mieczysław Tomaszewski

1972

In early May 1972, AMB had been scheduled to give concerts in Hamburg, Munich and Frankfurt. He played the first two but cancelled the third. In Frankfurt, he was evidently dissatisfied with the quality of pianos offered him. As reported in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , he said "I don't feel like it' when asked to account for the cancellation. His blunt language made no friends. The FAZ pubished an Opinion piece on 15 May, signed HL and headed "Irritating". On the 20th Carlos Kleiber came to the defence of his colleague. His arguments are similar to those he used in 1966 to justify his withdrawal from Berg's Wozzeck at the Edinburgh Festival. In essence, an artist has to be true to him/herself.

Charles Barber, Corresponding with Carlos : a biography of Carlos Kleiber

Michelangeli did not appear again in the USA after 1972, according to the Baltimore Sun, 23 April 1995.

September 19, 1972: Croisière Paquet “Renaissance”, Mediterranean Sea (Radio Broadcast | FLAC)

· Mozart: Piano Quartet No.2 in E-flat major, K.493

– Jean-Pierre Wallez, violin / Claude-Henry Joubert, viola / Frank Dariel, cello / Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, piano

– Aura 2000-2. This was recorded aboard a cruise ship.

Sunday 15 October, 1972: Stadthalle Wuppertal-Elberfeld, Germany including Brahms Op.10 and Schumann's Carnaval. Konzertdirektion: Rudolf Wylach (Wuppertal).

'The next concert programme with the Stuttgart Orchestra in the autumn of 1972 was of a completely different nature, predominantly virtuosic and effective: Weber's Euryanthe Overture, Grieg's Piano Concerto with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Richard Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, and Ottorino Respighi's I pini di Roma. The success must have been incredible, judging by the Stuttgart press reports. "What a job this Celibidache has done!" Wolfram Schwinger enthused at the time in the Stuttgarter Zeitung.

With this programme, they subsequently went on tour through the Federal Republic. I heard the Munich concert on 27 November, 1972, and could only confirm the impressions already recorded elsewhere. The concert was a triumph for Benedetti Michelangeli, the orchestra, and of course for Celibidache himself. He was also quite satisfied with the result of the evening, as I learned from him in the artists' room. Incidentally, it was an exceedingly long concert, so that in view of the late hour, Celibidache waived the encores he usually willingly gave.

Klaus Weiler, Celibidache - Musiker und Philosoph (2008)

24 December 1972: Il Piccolo di Trieste announces a musical Caribbean cruise in the Tropics with Bach, Vivaldi and Benedetti Michelangeli.

He is the one who will go with Pro Arte on the "Tropical Musical Cruise." And with the Munich orchestra, Benedetti Michelangelì will play. «The greatest pianist of all time, whom Italians let slip by taking his whims of a childlike genius too seriously.»

«Il massimo pianista di tutti ì tempì che gl’italiani. sì sono lasciati scappare per aver preso troppo sul serio le sue bizze di genio sempre bambino».

How two characters, two vital and existential temperaments, two antiithic aesthetic attitudes like Redel and Benedetti Michelangeli can find a single point of agreement

we will know after the cruise at the end of January. The oceanic

musical feerie will depart from Nice and, touching the Canary Islands, will

tour the major islands of the Caribbean. A twenty-one-day cruise for forty concerts, musical chats at the table over drinks, cocktails, and breakfasts for lunch. Participants included, in addition to musicians and musicians, some five hundred music lovers from all over Europe and America with bankable assets that we can only imagine.

1973

Concerts with Carlos Kleiber in Hamburg. New tour in Japan.

The New Yorker, 4 November 1972 had carried an advert, noting that ABM would be one of the artists on board (was he or wasn't he?!): The Sixth Music Festival at Sea aboard the Renaissance in the Caribbean, January 4-17, 1973. The Renaissance sails from Port Everglades, Florida. 'Write for colorful brochure or see your travel agent.'

In an interview with Dominic Gill in June 1973, AMB was asked if he was nervous before a concert. 'Everything depends upon the preparation. A recital is made by what has gone before, not by what happens while it is being played. (...) You've got to have the stage in your blood. Of course one is nervous in a sense, but I've been through a war and I know what being afarid means, because death is the same for everybody. (...) One must be built, or build oneself, in such a way as to be a victor always.' [I'm not sure this reference to war is a proper answer!]

On Saturday 6 January 1973, Corriere della Sera asked:

What are the hands of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli suffering from? An insurmountable barrier has been erected to protect the privacy of the celebrated pianist since yesterday in Verona. All that is known for certain is that his hands are entrusted to the care of Professor Giovanni De Bastiani, director of the university's orthopedic and trauma clinic.

Yesterday morning, the pianist was seen climbing the stairs of the hospital and reaching the first floor where the orthopaedic department is located. (But i does not seem serious despite the dark silence on the matter)

This medical detail may explain why H.M.V. sessions, originally intended for Piano Concertos by Grieg & Schumann with Michelangeli and Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos in late January 1973 at Abbey Road Studio 1 were transferred to Sir Adrian Boult and Wagner extracts. There exists a spectacular live recording of the Grieg with the same conductor and the New Philharmonia on Thursday 17 June, 1965: Royal Festival Hall, London.

With the Hamburg State Opera Orchestra, Kleiber led performances of Beethoven's Coriolan, R. Strauss' Death and Transfiguration and the Emperor Concerto with ABM (ten years older). It must have seemed like a bizarre pairing. For all that, it was later propose that they record the concerto together; their life performances had gone surprisingly well. In 1975, they gave it a strange try.

Charles Barber, Corresponding with Carlos : a biography of Carlos Kleiber

April 1973

Cord Garben picks up the story: 'It was fortunate that ABM, having closely followed the conductor's career, wanted a concert with Kleiber. Thus, the Hanseatic

audience was presented with a special event, for which music critics and audiences came from far and wide. All three concerts in the same subscription series (April 8, 9, and 11, 1973), to which Kleiber added Beethoven's Coriolanus Overture and Richard Strauss's Death and Transfiguration, were performed with the same group of musicians, including ABM. Critics noted a growing understanding between the two artists with each passing evening: Kleiber's new interpretation of the orchestral part of Beethoven's Fifth Piano Concerto was particularly appreciated.

Through unorthodox bowing and phrasing, he had effectively "lightened" the

string part, making it transparent. It goes without saying that Deutsche Grammophon

didn't want to miss such an event in the Hamburg Musikhalle—that is, right "on their doorstep"—without taking advantage of it. ABM was already contractually tied to the record company, while the recording of Freischütz with Kleiber was imminent. The ideal match had therefore been found, both artistically and commercially.'

London

'When ABM arrived in London in 1973, it transpired that his Steinway had been left out on the docks in Hamburg and that the action had suffered from damp. Twelve replacement, Steinways were tried and deemed inadequate. A substitute concert was arranged for a fortnight later. "He's still got 12 minutes to cancel," cynics reflected in the auditorium.

Daily Telegraph, 13 June 1995

18 March, 1973: Royal Festival Hall, London, England (Audience Recording)

Bach/Busoni: Chaconne from Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004

Schumann: Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Fantasiebilder), Op.26

Brahms: Four Ballades, Op.10

Brahms: Variations on a theme by Paganini, Op.35 [edited by Michelangeli]

*Encore: Chopin: Mazurka in G minor, Op.67 No.2

21 May, 1973: Lugano, Switzerland (Radio Broadcast )

Bach/Busoni: Chaconne from Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004

Schumann: Carnaval (Scènes Mignonnes sur Quatre Notes), Op.9

Brahms: Four Ballades, Op.10

Brahms: Variations on a theme by Paganini, Op.35 [edited by Michelangeli]

This can be heard on CD: Aura 978-3-86562-779-7

Beethoven, Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op.58?

'In the big mess of ABM's discography there are few certainties, but everything we know leads to rejecting the attribution of [a recording of Beethoven's Concerto No. 4 in G major Op.58] to him. We know that the performance (issued on CD by Exclusive and Legend) was taped in Belgrade on 7 October 1973 and the conductor was Zivojin Zdravkovic. Now, during that period ABM was not present in Belgrade (his wife is on record on this). The only time ABM played in Yugoslavia was in 1971. There are no other ABM recordings of the Beethoven IV, and there is no evidence that he ever performed the concerto in public. However, there is evidence that Maria Tipo - incidentally, a wonderful and underrated pianist - played the Beethoven IV on that date in the capital of the former Yugoslavia. Having said that, it is a terrific performance regardless of who was the actual pianist.' (Paulo Pesenti)

'Also on the programme was Debussy La Mer and Sofoson 1 by the Serbian composer,

Branislava Šaper Predić. The original broadcast, in fine sound, is identical to this wishywashy bootleg. The confusion was brought about by a famous pirate LP label wishing to obfuscate the issue and make some money out of it.'

("Noël", Slipped Disc blog, January 2020; confirmed by the Belgrade Philharmonic archive)

Jornal do Brasil (16 April 1973): 'The Italian Cultural Institute in Rio de Janeiro informs that the Escola Musical da Vila Schifanoia, in Fiésole, near the city of Firenze/Florence and one of the most picturesque corners of Italy, has opened enrollment for its 1973-1974 academic year of training courses for young pianists. These courses, lasting three years, are directed by Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in collaboration with Professor Orazio Frugoni, director of that school, which in recent years has achieved great international renown. Registration precedence is established.'

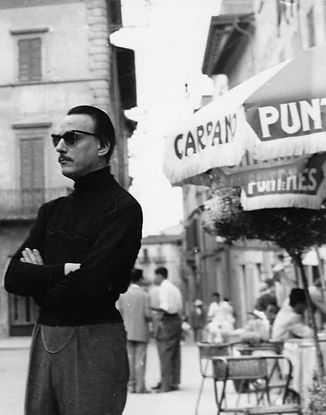

You can see ABM's red/brown hair clearly here, before he dyed it jet-black (Toronto 1970)

Japan

A recording exists of Beethoven's Sonata n. 4 in E flat major, Op. 7 with ABM playing in the NHK Hall , Tokyo on 20 October, 1973

24 October, 1973: Dai Ichi Hall, Kyoto; 3 November: Festival Hall, Osaka

Daiichi = ?Rohm Theatre Kyoto, officially known as Kyoto Kaikan

29 October, 1973: Bunkakaikan, Tokyo, Japan

· Schumann: Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Fantasiebilder), Op.26

· Chopin: Piano Sonata No.2 in B-flat minor, Op.35

· Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales

· Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit

(Personal note: I bought my copy of a 2CD set of this recital in Tower Records, Shibuya, Tokyo in April 2014)

Japanese Wikipedia has this (unsourced): His first visit to Japan in 1965 shocked (presumably in a pleasant way) the Japanese music world. He has visited Japan several times since, but only this first visit performed as scheduled. His subsequent cancellations have been met with turmoil. During his second visit in 1973, he changed concert dates and venues due to poor conditions, and some performances were canceled. He returned the following year in 1974 to make up for the previous year's performances.

CD liner notes (from the Japanese)

'In the autumn of 1973, Michelangeli was scheduled to perform six concerts, including those in Kyoto and Osaka, with three different programmes, starting with a recital at the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan on October 15th and ending with a recital at the NHK Hall on November 21st. The invitation was from the Japan Cultural Foundation, with support from the Asahi Shimbun Company, Asahi Broadcasting Corporation, FM Tokyo, and FM Osaka.

I had planned to broadcast the first of these concerts on the 19th as part of the "TDK Original Concert" programme, which was then produced by FM Tokyo.

'Michelangeli was rumoured to have been a nervous and difficult-to-please pianist, and was known for his habit of canceling concerts at the last minute, a reputation known as the "cancellation scientist." (1965, Yomiuri Shimbun). When the company first invited him, his manager, the late Takayanagi Masuo, apparently used this to his advantage to promote him, selling tons of tickets while saying, "He won't play (even if he comes to Japan) He won't play!" (Takayanagi would continue to brag about this for years to come.)

As expected, the opening recital in 1973 was canceled at the last minute. This meant I had to abandon my plan to broadcast it before NHK (NHK supposedly aired the 20th October recital at NHK Hall on their FM program on the 26th).

'In the end, we were able to record the recital hosted by the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre on October 29th. The programme was the same A-programme as the 20th. The broadcast date was delayed until December 21st, but it was only natural that everyone was grateful that it could be broadcast at all. However, on the day of the broadcast, the manager himself was obviously on edge, even to an outsider. He was standing in front of the stage, facing the one-point stereo set up.

'Michelangeli's [the manager's?] face turned pale when he saw the hanging microphone, and he asked that it be removed, because he didn't know what the Master would say if he saw something like that (meaning that he might get angry and call off the concert, saying it was an eyesore). He also harshly warned me that during practice, the master would alternate between playing the piano on stage and one in the wings, and that none of the staff should ever come face to face with the master during those sessions.

'Fortunately, Michelangeli didn't say anything when he saw the microphone set up at the front of the stage. He continued to play the two pianos, silently going back and forth frequently between the stage and wings. It didn't seem like he had any particular intention of using his favorite piano. He must have had his own unique way of thinking. We, the staff, were also enjoying the game of hide-and-seek, laughing like bad boys running away from the scary teacher.

'It was some time after the rehearsal that I panicked for a moment. For some reason, he also looked taken aback. Naturally, my manager hadn't introduced me to the maestro, so I belatedly exchanged a few greetings. Michelangeli then asked, somewhat hesitantly, "Are you the radio man? I've already finished the rehearsal, but is the mic test enough?" It turned out he was fully aware of the situation and was being considerate in his own way. Naturally, he wasn't averse to being recorded or anything.

'Even so, Michelangeli's performance that day was captivating beyond words (...)

The atmosphere was so intense it was almost overwhelming, and I felt as if I had been given a glimpse of the demonic sensations hidden behind this maestro's intelligent control, which left me speechless.'

(Music critic, former producer at FM Tokyo)

On 9 December, 1973, 'Maestro Benedetti Michelangeli gave a recital at the Salle Pleyel in Paris, entitled "Mémoire du Martyre du Juif Inconnu."'

1974

April 5, 1974: Teatro Apollo, Lugano, Switzerland (Radio Broadcast | AAC256)

· Haydn: Piano Concerto No.4 in G major, Hob.XVIII:4

· Mozart: Piano Concerto No.15 in B-flat major, K.450

– Edmond de Stoutz / Züricher Kammerorchester

Victoria Hall, Geneva, Switzerland

'In short, what we witnessed on Sunday evening was a piano recital with orchestra, as the audience had clearly come to hear Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli! The programme was perfectly suited to this, as it included no less than two concertos. In this regard, the soloist cannot be praised enough for choosing two little-known pieces: Joseph Haydn's beautiful Concerto in G major, whose concertante work for keyboard is hardly ever performed in public, and W.-A. Mozart's admirable K. V. 450 in B flat major, rarely performed in concert halls. ... The great Italian once again proved himself to be an outstanding performer. What refinement in his limpid playing, with its marvellous evenness of touch! But also what taste in the design of the lines, never gratuitously virtuosic, always expressive! And finally, what musicality in the shaping of a phrase, carried through to its full meaning with exemplary sobriety! Despite all the reserve with which the pianist surrounded himself, he was the object of endless ovations from an audience which, beyond its apparent coldness, was able to recognise his profound, authentic sensitivity. Mr Edmond de Stoutz, who, at the head of the Zurich Chamber Orchestra, was a valuable collaborator for the soloist, gave a very fine performance of Mozart's famous Symphony in G minor at the beginning of the evening.'

Courrier de Genève, 9 April 1974

Sunday, 19 May 1974, Municipal House – Smetana Hall, Prague

Ludwig van Beethoven: Egmont. Overture op. 84

Edvard Grieg: Concerto in A minor for piano and orchestra, op. 16

Bohuslav Martinů: Symphony No. 6 /Symphonic Fantasies/

Prague Symphony Orchestra – FOK; conductor Ladislav Slovák

The incomparable Benedetti-Michelangeli. The famous Italian pianist performed in Prague again after several years. In Grieg's piano interpretation of the concerto with two masterful encores (Chopin's Mazurkas), he once again confirmed that he belongs to the greatest piano masters of our time. His musical expression ranges from dematerialized pianissimos to highly dramatic peaks, a fantastic perfection in which there is no trace of self-interest, created a completely new experience from this concert, as if cleansed of all usual mannerisms and yet deeply effective in its pure aesthetic beauty. I think it goes without saying that this unique art also had a unique response.

Jaromír KŘIŽ, Večerní Praha 20.5.74

Tel Aviv (October 1974)

The Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition (Tel Aviv) came into being

in 1973, at the initiative of Jan Jacob Bistritzky, a close friend of Arthur Rubinstein, who was honored to give his name to the Competition. The Competition first took place in

1974 and is held every three years. ABM served on the jury for Septmeber 1974 and 1977. The winners were Emanuel Ax and Gerard Oppitz respectively.

Bistritzky, who emigrated from Poland in 1971, had brought his professional expertise with him. In Warsaw, he had already directed the world-famous Frederyk Chopin Institute and the Chopin Piano Competition.

For 1974, members of the international jury included Arthur Rubinstein, Guido Agosti (Italy) and Jacques Fevrier (France), friend of Poulenc since childhood

11 September 1974, Mann Auditorium, Tel Aviv, Israel: Beethoven's Sonata Op.7 in E flat 'sounded strange because of irrelevant musical gestures and mannerisms which seemed to place the artist's empathy with the music in question. Neither did the intensely emotional second movement, the Adagio which crowns the work, amount to anything spectacular. The third movement, which has the sudden switch to the dark minore seemed to inspire Michelangeli's imagination. He gave a stunning performance of the four Ballades of Brahms. Although it may not have been to everyone's taste, there can be no doubt that only Michelangeli can play them as he did.' The Jerusalem Post (16.9.74)

The Hungarian-langauge Új Kelet (20.9.74) wrote: One of his increasingly rare public appearances, which he did not cancel at the last minute, ... In addition to his excellent piano playing, our artist has become famous for this. He demonstrated his sympathy for our people with the concert dedicated to the "memory of the unknown Jewish martyr" held in the Salle Pleyel in Paris in December of last year. (...) He played Brahms's four ballads Op. 10 so spiritually that we imagined ourselves at a séance conjuring up astral bodies. [S amint oly átszellemülten játszotta Brahms négy balladáját Op.10 hogy asztráltestek szellemidéző szeánszán képzeltük magunkat.] There is something in Michelangeli, an almost ghostly trait abstracted from the world and, at the same time, a tendency to break it down into atoms: Beethoven's E flat major, Op. He analysed the emotional Largo movement of his 7th sonata almost bar by bar, breaking it down into small parts, but in the closing rondo his eternal Italian singing inclination awoke in him and he led through and built up the folk-like themes with delightful ease. As an encore, he played Debussy's youthful ‚Hommage à Ravel“ with unsurpassed elegance, as a silent confession of an esoteric, carefully secluded from the outside world, with an overly refined nervous system, an excellent performer.

LÁSZLÓ PATAKI

'As for the best piano playing of any kind heard in Israel during those eventful weeks, that was provided by the redoubtable Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli of Italy. Prior to joining Rubinstein and Eugene Istomin as a juror for the final stage, Michelangeli offered an “Hommage a Israel” recital in Mann Auditorium, with all the receipts donated to the funding of the Rubinstein competition. It is all too long since Michelangeli (the Italians call him “Benedetti”) has been heard in the United States—1968. But the interval has only added to the mastery that makes him, at 50, the greatest living craftsman at his specialty of casting spells and conjuring up pianistic miracles.

'When he had caressed the keys and solicited the strings’ cooperation in his concepts of Beethoven’s Opus 7 Sonata, the four Ballads (Opus 10) of Brahms, and the B-flat Minor Sonata of Chopin, he responded to a tumult of applause by spinning the measures of Debussy’s “Hommage a Rameau”—which few pianists risk in public—into a weblike filigree of sound both imaginative and impalpable. Challenged to explain why he has neglected America so long, Michelangeli responded that it was too far away, that he could play many more concerts in Europe during a week than in the States. If Italy wants Congress to help out in its financial dilemmas, it had better get “Benedetti” over here, subito

Irving Kolodin, Saturday Review (19 October 1974)

Tuesday/Wednesday 15/ 16 October, 1974: Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris, France (WATCH HERE)

· Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.5 in E-flat major, Op.73 (Emperor)

– Sergiu Celibidache / Orchestre National de l'ORTF

– Also on an Electrecord LP

1973年、アルトゥーロ・ベネデッティ・ミケランジェリは再び来日し、東京・京都・大阪で演奏しました。

このウェブサイトの作者は、2014年4月に渋谷のタワーレコードで、そのリサイタルの一枚のCDを購入できて大変喜びました。