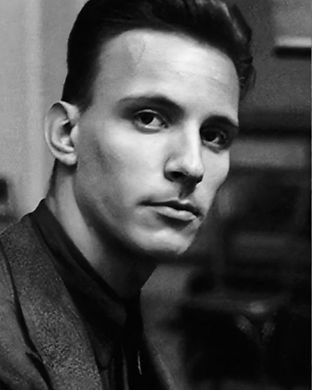

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

Early Years

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was born in Orzinuovi near Brescia, Italy, the first-born of Giuseppe and Angela (known as Lina) Paparoni.

His date of birth is usually given as 5 January 1920.

He himself once said that he was born 'during the first hour of the morning of 6 January 1920'. He was baptized on January 29th with the names Arturo, Francesco, Andrea, and Giovanni Maria.

His parents had moved to Brescia from Massa Marittima (in the Grosseto area) on 22 December, 1919.

Italian by nationality, he always claimed his roots were Slavic and often spoke of having Croatian ancestry. Regarding his birthdate, Howard Klein in The New York Times (16 January 1966) wrote: 'A previous attempt to get his correct birthdate - January 5 is given in Thompson's Encyclopaedia- was met with, "It is not important, but it happens to be January 6."'

'He proudly admitted his Croatian ancestry. "You can say ‘di anima Slav, di cultura Austriaca…’ I’m of Slavic origin and still a bit of a Slav," he confessed to Dominic Gill in a 1973 interview. "I’m certainly not Latin." Slav or not, he is said to have felt less at home in Italy than in Austria, which he called "my country"'. In 1976 he told Silvio Bertoldi that his mother was a Yugoslavian.

It is said that he claimed to be a descendant of Jacopo dei Benedetti—aka Jacopone da Todi—the 13th-century Umbrian poet (c. 1230 – 25 December 1306). Benedetti Michelangeli created a 'descent from an ancient lineage, which redeemed the grey reality of a lower-middle-class family with a father and mother who were unemployed and had limited economic means.'

The other branch of AMB's "family romance" dates back to the 1970s, after Benedetti Michelangeli had disdainfully abandoned Italy. In interviews, he stated that his family was of German origin, Benedikter. He also said he had been a bomber pilot during the war. It seems clear that in this case, Benedetti Michelangeli was "appropriating" his father's wanderings with the South American diplomat and making his dream of military glory realistic. [Orphaned at an early age of both parents, Giuseppe had been tutored by a South American diplomat who had taken him with him to the various countries where he served.] (Piero Rattalino)

His father, who was a count and a lawyer by profession, was also a musician and a composer and began teaching music to Benedetti Michelangeli before he was four years old. Michelangeli learned to play the violin at the age of three and would later study the instrument at the Venturi Institute in Brescia, before switching to piano under Dr. Paolo Chimeri, who accepted him into his class following an audition.

At home [at one stage they lived on Via Lattanzio Gambara, in a house now demolished], in an environment dominated by an innate predisposition and keen interest in music, little Ciro – as Arturo was called for some of his curls which made him resemble Cirillino, a then well-known character in Corriere dei Piccoli – began studying the piano at three years of age, under the guidance of his father.

At four years of age, Arturo gained admission to the Venturi Civic Institute of Music in Brescia, as a pupil of maestro Paolo Chimeri, and at seven years of age, on 10 March 1927, he aroused general amazement and admiration when he performed for the first time before an audience, during the recital marking the end of the 1925-26 two-year course of studies.

Michelangeli once said: "I learned everything I know from Paolo Chimeri."

(GUIDETTI, Giuliana. Vita con Ciro. Palermo: L’Epos, 1997)

He was taught at home by his mother and did not attend elementary school. This lack of contact with his peers (social interaction etc.) may in some part explain his demanding, intolerant behaviour, tantrums & so on in later life. 'The child's entire world was confined to the home. He remained in a sort of tower unfavourable to learning about life among his peers. Simply put, when Arturo left home, it was for the piano. He never attended music school, and even his diploma form the G. Verdi Conservatory in Milan was obtained privately. Another reflection of his childhood and adolescence concerns audiences, which he feared, in the guise of that superego that could even destroy him. Even his meticulous preparation of concert pieces was linked, from the beginning, to the fear that a mistake could lead to a negative, irreparable judgment.

He once said: "Only with music am I not shy".

Psychiatrist Vittorino Andreoli, Classic Voice (15 January 2022)

In the spring of 1929 he attended private lessons with maestro Giovanni Maria Anfossi in Milan, where his mother accompanied him each week. Anfossi was a teacher at the Collegio Reale delle Fanciulle and owner of his own school.

Giovanni Anfossi (Ancona, 6 January, 1864 - Milan, 16 November, 1946) was a descendant of the famous opera composer of the Neapolitan school Pasquale Anfossi (1727-1779), who became famous throughout Europe for his comic operas. Giovanni founded a music institute in Milan named after his descendant and devoted his entire life to piano pedagogy. His numerous students included Luisa Baccara, a Venetian pianist, lover of the poet Gabriele D’Annunzi, with whom she lived in close proximity until his death.

He took the piano license exam at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan in the fall session of the 1930-31 school year; at the same conservatory, he took the diploma exam privately on 12 June, 1934 (at only 14 years and 5 months of age), obtaining scores ranging from 6 to 10 in the various tests, with an average of 8.50. The program for the actual performance exam, graded 10 and including the first book of Brahms's Paganini Variations on a Theme, Op.35 [see below for ABM's idiosyncratic way with them] and Ravel's Jeux d'eau demonstrate that fourteen-year-old Benedetti Michelangeli was a complete pianist. (Piero Rattalino)

'The diploma could have been logically followed by enrolment in the advanced course at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, taught by Alfredo Casella. Benedetti Michelangelo, however, continued studying for another five years with Anfossi, who, with his forty years of teaching at the Collegio Reale delle Fanciulle, had established a dense network of relationships in high society—the dedications of his music are a sample of Milanese elite—and who also owned a villa above Stresa, where during the summer he hosted his best students, whom he "exhibited" in the grand hotels of the very exclusive tourist centere on Lake Maggiore.' (Rattalino p.11)

A correspondent Diana (from Siberia) questions whether Michelangeli and his family could have actually afforded such lessons. She highlights a passage in Piero Rattalino's book Da Clementi a Pollini (1983) concerning another Italian pianist Carlo Vidusso:

«Era invece andato a Tremezzo per farsi sentire da Schnabel e avrebbe desiderato studiare con Schnabel; ma il prezzo della lezione — cinquanta lire, se ben ricordo — era troppo elevato per lui, e da Schnabel non era pit tornato". [p.449]

("Instead, he went to Tremezzo to gain Schnabel's attention and would have liked to study with him; but the price of a lesson - fifty lire, if I remember correctly - proved too high for him, and he never returned to Schnabel.")

'Could Arturo, a young man of fourteen to sixteen years old,' Diana writes, 'whose family was experiencing serious financial difficulties, afford to go to Rome (and live there) or study at the summer courses with Schnabel? Carlo Vidusso was 23 years old when Schnabel began holding summer courses (Vidusso is nine years older than Benedetti Michelangeli); he was an adult, already engaged in concert activity (in 1934 he performed in Milan, Venice, Rome and other cities), therefore, financially independent, but he did not have the opportunity to study with Schnabel, because the lessons turned out to be significant in price.'

She also points out that the future, Michelangeli held courses for his students free of charge. But his older colleagues did not.

'His failure to attend public school—piano and violin lessons at the Venturi Institute in Brescia were, obviously, not group lessons—did not foster a sense of socialization in the child. Throughout his life, he maintained a few close friendships, with those who recognized his superiority at all times, and had no significant social or intellectual relationships except one, with the orchestra conductor Sergiu Celibidache. The birth of a younger brother in 1924, which provoked feelings of jealousy in him, and of a younger sister in 1926, who died at the age of seven, also played a significant role in shaping his personality. (Piero Rattalino)

In October 2022, a plaque dedicated to Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, who was born at Via Milano 100/E, was unveiled in the Fiumicello neighbourhood of Brescia. Does this conflcit with the birthplace given above as Orzinuovi, near Brescia?

His first Chopin & Beethoven Op.111

'The following spring, on April 17, 1932, young Arturo played in Brescia, in an evening in support of Catholic Action. The twelve-year-old performed, among other items, the difficult Prelude in B-flat minor Op. 28 No. 16, by Chopin. It was the first time he brought a work by the Polish author to the public...

'During the concert, he also played music by Scarlatti, whose rediscovery begins in Italy with Alessandro Longo, a contemporary of Anfossi, who studied at the school of Beniamino Cesi and was director of the Conservatory of Naples. Longo carried out the revision of the entire sonata corpus of Domenico Scarlatti.

-----------

'Benedetti Michelangeli played again in Brescia in May [1935?], presumably on the 6th and the following day. Vittorio Brunelli in Il Popolo di Brescia writes with foresight: "Today we have a great pianist, tomorrow we will have a great pianist and a great interpreter together".

'During the concert, the young man played Sgambati's Étude mélodique (I believe it is op. 21 no. 5 in B minor) and noted it as unpublished in the repertoire of the Brescia native.'

-----------

'[After a piano competition in Genoa] both the magazine Musica d'oggi (February 1938 issue) and the Rivista musicale italiana of January 1st, 1938 report this:

"At the Royal Conservatory L. Cherubini of Firenze/Florence, the second Consolo competition for young Italian pianists was judged with a prize of 5,000 lire. 19 candidates from 15 cities in Italy participated in the competition, the prize was awarded to the young Dario Cagna of Milan. The young Benedetti Michelangeli Arturo of Brescia, Golia Maria of Milan, La Volpe Lodovico of Naples, Macarini Carminiani Gherardo of Rome were also singled out as elements of the highest order and worthy of consideration by national and foreign concert organizations."

-----------

'January 29, 1937, he played again in Brescia, offering in concert Roncalli (Passacaglia), Turrini (Presto), Beethoven (Sonata op. 111), Chopin (two Mazurkas, two Preludes and an Etude), Albeniz (Navarra), Margola (Tarantella rondo in first performance), Debussy (L'Isola gioiosa/L'Ile Joyeuse), Liszt (Hungarian Rhapsody No. 12 and Polonaise in E major, grande polonaise).

'We read in the Popolo di Brescia by Antonio Grassi on December 31:

"Certainly Benedetti's interpretation is flawless, especially in the second part [Sonata op.111] where the artist's power of penetration and translation must struggle against the sublime, but Beethoven would have caressed the head of this boy so bold and so talented, that is, supported by two wings that can carry so much upwards."

"Di certo è senza pecche l'interpretazione del Benedetti, specialmente nella seconda parte [Sonata op.111] dove il potere di penetrazione e di traduzione dell'artista deve lottare contro il sublime, ma Beethoven avrebbe accarezzato la testa di questo ragazzo così ardito e così bravo cioè sostenuto dalle due ali che possono portare molto in su."

Antonio Armella, I concerti di Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (2025), 12, 15, 16

Childhood memories...

In 1980, journalist Renzo Allegri asked Dr Arnaldo Lenghi, a doctor who had been ABM's friend for 45 years (source unknown):

- What was Benedetti Michelangeli like back then?

LENGHI: “A normal boy. We were in high school, but he was already a piano teacher. In terms of maturity and intelligence, he was far superior to the rest of us. But even then, he was shy and reserved. He feared being thought different from the others. He was a man of very few words. In fact, he almost never spoke, but everyone sought his company. He inspired instinctive sympathy.

"He had a great desire to play, but he was forced to spend his days glued to the piano. His mother, inflexible, watched over him and guided him. Sometimes he managed to escape and come with me and Umberto. He had begun studying piano at three. At four, he enrolled at the Venturi Music Institute in Brescia, and at five, he gave his first public concert. At 14, he had already graduated in piano, violin, and organ. He had never experienced the carefree games of children his age, and he resented it. In his family and among friends, everyone called him Ciro. We still call him that today.”

Myth-making

'Apparently, Michelangeli had no more teachers from that point, but the lack of certainty may be due to his tendency to shroud his life with an aura of mystery and confusion. During his teenage years he studied medicine to placate a father who did not want him to take music as a career, but Michelangeli returned to music and by the age of nineteen was of a high enough standard to win the first International Piano Competition in Geneva.'

Jonathan Summers

Camilla Cederna once wrote in Corriere della Sera (27 November 1988):

"He gave his first concert at the age of four, dressed as a girl and with hair as white as his skin. Why? As a child, he was an albino, he replied: a special treatment managed to change his hair colour, "but the trouble is that I'm still an albino inside," he continued.

"I feel great in the dark, I hate the sun because it hurts me, I love twilight, and whatever good I've done, I've done during the full moon, as soon as it begins to wane." So he spoke of himself as a werewolf, making it up, of course; a kind of werewolf who, albeit melodiously, howled, and all to see me raise my eyebrows in amazement."

Michelangeli invented many things when he spoke about himself. He invented the idea of being a descendant of a Russian prince. Why he did this remains a question mark. Perhaps he wanted to hide things about himself. Perhaps it was simply a way to poke fun at certain aspects of his own world, the world he was born into, the world he came from.

I mention this to warn against many statements made and many anecdotes told, because many things are the product of invention, or are exaggerations and embellishments of what was only partially true.

Ottavio di Carli (1999)

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was born in Brescia, but his family was Umbrian, and to these hidden and arcane origins he traced his aspirations to an essential mysticism, perhaps linked to Jacopone da Todi, a member of the noble Benedetti family.

Patrizia Gracis (1950-2013) is credited with the creation of a documentary, entitled The Secret Umbria of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, which was screened at Palazzo Trinci in Foligno on May 31, 2009, as part of the concert season of the Amici della Musica di Foligno. The film—which alternates interviews with musicians, musicologists, historians, and philosophers with shots of evocative Umbrian landscapes—dedicates considerable space to Arturo's father, Giuseppe Benedetti Michelangeli (Foligno, April 17, 1882 - Brescia, January 20, 1957), a lawyer but also an accomplished musician.

[Patrizia Gracis, a Venetian, daughter of the orchestra conductor Ettore, was then a professor at the "Francesco Morlacchi" Conservatory in Perugia and had purchased a house

in Monteluce, whose terrace offered a splendid view of the Umbrian hills.]

'We do not know when or with whom Giuseppe began his musical studies, but he was a student in Rome of the great Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914), who introduced him to non-operatic music, then neglected in Italy, to a knowledge of counterpoint, to an admiration for the piano and the works of Liszt, of whom Sgambati had been a disciple, to the world of Wagner, and to the entire German musical tradition. The important contact between Giuseppe and Sgambati is linked to the long period that the Roman musician spent in Umbria.

Biancamaria Brumana

'Michelangeli's transition from celebrity to myth occurred when, in 1964, he held concerts in Moscow and Leningrad. Russia - which had scattered a dense group of piano heroes around the world - prostrated itself reverently in front of the Italian who came from a peripheral piano culture.' (Igino Vaccari)

An Italian piano tradition?

'Ferrucio Busoni, ruler of the concert scene, was born in Empoli (Tuscany) but worked in Germany. Only in the twentieth century did there appeared the first Italian who could compete with the most important pianists of other nations: it was Carlo Zecchi, born in 1903. Michelangeli, born in 1920, was the second. Benedetti Michelangeli was a pure cultural product of Italy, or rather of Lombardy. In Milan he graduated at the age of fourteen and he did not take master classes with famous pianists while continuing to study with his teacher.'

(Igino Vaccari)

Ferruccio Busoni (1866 – 1924) was born in the Tuscan town of Empoli on 1 April 1866. He made his public debut as a pianist in a concert at the Schiller-Verein in Trieste on 24 November 1873. He then studied at the Vienna Conservatory (aged 9-11) and afterwards with Wilhelm Mayer (in Graz, Austria) and Carl Reinecke (Leipzig, Germany). In the mid 1880s, Busoni was based in Vienna, where he met with Hungarian-born Viennese composer Karl Goldmark and helped to prepare the vocal score for the latter's 1886 opera Merlin. In 1888, the musicologist Hugo Riemann recommended Busoni to Martin Wegelius, director of the Institute of Music at Helsingfors (Helsinki, in present-day Finland, then part of the Russian Empire), for the vacant position of advanced piano instructor. This was Busoni's first permanent post. Amongst his close colleagues and associates there were the conductor and composer Armas Järnefelt, the writer Adolf Paul, and the composer Jean Sibelius, with whom he struck up a continuing friendship.

Wis, Roberto (1977). "Ferruccio Busoni and Finland". Acta Musicologica. 49 (2): 250–269.

Carlo Zecchi (8 July 1903 – 31 August 1984) was born in Rome. A pupil of F. Baiardi for piano and of L. Refice and A. Bustini for composition, he began his career as a concert pianist at only seventeen years of age. He later studied piano with Ferruccio Busoni and Artur Schnabel in Berlin. He led pianistic courses in Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rome, and in Salzburg. He was a highly acclaimed performer of the works of Domenico Scarlatti, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Claude Debussy and of other Romantic music. He died in Salzburg. From 1941, - due to a car accident he was involved in 1939 where he injured his hand - Zecchi devoted himself to conducting.

'The Benedetti Michelangeli of the early 1950s, in order to achieve a conscious interpretation of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Brahms "had to conquer for himself, with tenacity and dramatic skill, what for the German interpreters of his generation was a given of education," (Piero Rattalino) and he did so by overcoming the limits imposed on him by his own cultural education, which took place in Fascist Italy in the 1930s...'

[Jerzy Miziołek]

'In Italy, Puccini's death in 1924 marked the moment when, after centuries, Italian opera ceased to enrich the repertoire of musical theatre. The artists of Puccini's generation

went into disuse, while Respighi, Pizzetti, Malipiero, and Casella became the new leaders of musical life.'

'With the exception of Busoni, who did not live on the Italian Peninsula and who only indirectly influenced the evolution of national culture, in 1920 there was no concert pianist of great international prestige on this side of the Alps.'

'Alessandro Longo (1864-1945), highly respected in the South and fiercely opposed to any "modernity," teaches at the Naples Conservatory.'

[Piero Rattalino]

Today, Longo is mainly remembered for compiling an almost comprehensive catalogue of the keyboard works of Domenico Scarlatti. For many years, Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas were conventionally identified by their Longo numbers, but these were later superseded by those found in Ralph Kirkpatrick's catalogue. Longo's Catalogue originated in his landmark full publication of the works of Scarlatti in 11 volumes [Ricordi, 1906-1913] and implied particular groupings of the sonatas, the chronology of which was later completely revised and differently grouped in Kirkpatrick's (Princeton) 1953 study of the composer.

------------------------

Michelangeli had not studied in Paris, but in Brescia and Milan, and in the Milan not of the Conservatory, but of the ladies of high society. But in Italy in those years, we have also said that a new cultural revival was underway, that of the entire eighteenth-century world; in other words, what we conventionally call 'neoclassicism' had spread. It was during these years that Vivaldi was discovered, which meant that performing Vivaldi meant being in step with the times, being modern. Indeed, the neoclassicism of Casella, Respighi, and others was riding the wave of many recent musicological discoveries, and vice versa.

Musicological discoveries were often driven by a search for music from the Italian instrumental tradition, especially from the eighteenth century. Underlying this attitude was, of course, a nationalist culture, supported and fueled by the Fascist regime, which saw the predominance of Italian music even in the instrumental repertoire. Thus, attempts were made to recover and valorize even that which had fallen into oblivion, often without the philological rigor that is considered indispensable today. Transcriptions were therefore made at will, mostly transposing to the piano what was originally written for strings, harpsichord, or other instruments. In this context, Michelangeli adapted by studying Scarlatti and all the Italian harpsichordists, and incorporating works into his repertoire that today are considered incredibly kitsch or even unheard-of monstrosities, which nevertheless responded to the tastes and dictates of the time.

Bach-Busoni's Chaconne fits naturally into this context, and it's easy to understand why Michelangeli performed this composition, which is almost never performed again today.

Gianandrea Gavazzeni recounted this: "I remember a week in Naples. Benedetti was supposed to record albums with the Scarlatti Orchestra, and he didn't record anything. I met him every morning at the Excelsior and said, 'Are you recording today?' And he replied: "I don't know, I can't find the sound..."

Enrico Filippini, ‘… se Benedetti Michelangeli non trova il suono?’, in Repubblica, 28 aprile 1977; reported in Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Il Grembo del suono, Catalogo della mostra, Milano, Skira, 1996, p. 108.

Putting all these aspects together, we can perhaps better understand the reasons behind that Bach-Busoni, that famous Chaconne that became one of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli's most profound and moving interpretations: there is, in fact, the neoclassical reinterpretation of the past (Bach reinterpreted through Busoni's pianism, as was customary in Italian culture at the time), there is the prodigious technique, and above all there is the cult of sound, which turns the piano into a true orchestra. It's no coincidence that this very piece inspired Giovanni Testori's beautiful article in the Corriere della Sera on February 3, 1979, titled Il Grembo del suono (The Womb of Sound). This title was later reused for the exhibition on the pianist held in Brescia in 1996.

Ottavio di Carli (1999)

Cesare Augusto Tallone, piano tuner

(Bergamo , 10 May 1895 – Milan , 4 February 1982 )

Text of Michelangeli's telegram: "You are most earnestly requested to take the first plane to Palermo. This is absolutely necessary due to the atrocious conditions of the pianos, which only your magic will make possible. Thank you, Michelangeli . "

It was Anfossi who introduced his talented young student to Tallone. Cesare Augusto Tallone describes the meeting as follows: "One day in the spring, I believe in 1935, Maestro Anfossi came to me with one of his students. Introducing him to me, he said: 'Listen to this young man, destined for the greatest successes in the piano world; help him and follow him.'

It was Benedetti Michelangeli. Of noble appearance, tall for his youth, he placed his prodigious white hands on the keyboard and emerged like an astral light.

Libertà, 19 April 1971

The Michelangeli - Tallone couple became inseparable, Tallone followed him to many of his concerts during his tours. "Cesarino" himself (76 years old) in “Libertà", 19 April 1971 declared that he had not failed to assist him by following him to his concerts in 35 years.

Although he does not mention the dates, Tallone talks about the tours in the company of Michelangeli in his book (cit., Milan 1971). He mentions London [it is probably the tour after the First World War], he also writes that he got to know Germany, Austria, Portugal, Spain [40-41], he went as far as Montreal and Toronto [48 - 50]; he got to know Israel and Jerusalem [1967].

Cesare Tallone focuses in his book (published Milan, 1971; is it the same as Cesare Augusto Tallone, Fede e lavoro: memorie di un accordatore, Rugginenti, Milano 2021?) in particular on the Athens-Khartoum-Johannesburg tour (see his book chapter "Flight to the South"). He makes numerous observations in the chapter "From Travel Notes in South Africa," regarding the natural beauty and misery of South Africa. Tallone, though his spirit is focused—and inspired—on the perennial search for harmony and beauty, is not insensitive to his surroundings, and here his profoundly human gaze focuses on the social discrimination of those places. He reports on the miracle performed by Michelangeli and the Boccherini Orchestra, resulting in the enormous attendance at the concerts in Johannesburg. He does not mention the date, so I thank Stefano Biosa, founder of the “Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli” Documentation Centre, who confirms it to be February-March 1959.

In Gente (1975), Tallone expresses perhaps the most complete thought on Michelangeli: “The greatest artist I have ever known is Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. It’s difficult for me to talk about him, because I loved him, and still do, like a son. I met him for the first time when he was twelve. Maestro Anfossi, who gave lessons to my sister Ponina, told me he had discovered an exceptional talent and begged me to hear it. He brought the twelve-year-old Michelangeli home to me. The boy sat down at the piano, and after five minutes I was won over. I put my hand on his shoulder and said, ‘I will always follow you.’ And so it was. For 35 years I followed Benedetti Michelangeli all over the world. I spent unforgettable hours and days with him. The best moments were during trips—on trains, on planes, in hotels, on stage—when we could talk about music and a thousand other things. Michelangeli is a man of exceptional kindness and extraordinary intelligence. As a boy, when we first met, he never spoke. He loved me, though. Our souls had met immediately. Michelangeli even came twice a day from Brescia to Milan to spend some time with me. He didn't say anything to me. He watched me work, then we walked, always in silence, through the city, and in the evening he took the train and returned home. I was immediately struck by the way he studied music. He, like me, always considered the piano a living creature. He sat at the piano and sought a dialogue with the instrument. When he decided to record an album of music by Rachmaninoff and Ravel, he retreated to my villa on the island of San Giulio, in Lake Orta, to study. For a whole month he played day and night, forgetting to eat, sleeping, losing weight, and never speaking to anyone. I felt like I was witnessing the miraculous transformation of a human being into music. It seemed as if the melodies were penetrating his veins, becoming blood, the lifeblood of his existence. It was an incredible and exhilarating experience.'

Cesare Augusto Tallone, Fede e lavoro, memorie di un accordatore, Milano 1971

Brahms, Paganini, Michelangeli

Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 35, is a work for piano composed in 1863 by Johannes Brahms, based on the Caprice No. 24 in A minor by Niccolò Paganini. It was a trademark early work in Michelangeli's repertoire.

The work consists of two books. Each book opens with the theme, Paganini's Caprice No. 24 in A minor, followed by fourteen variations. The final variation in each section is virtuosic and climactic.

Brahms intended the work to be more than simply a set of theme and variations; each variation also has the characteristic of a study. He published it as Studies for Pianoforte: Variations on a Theme of Paganini. The work was dedicated to the piano virtuoso Carl Tausig. It is well known for its harmonic depth and extreme physical difficulty. Clara Schumann called it Hexenvariationen (Witches' Variations) because of its difficulty.

“Brahms and Paganini! Was ever so strange a couple in harness? Caliban and Ariel, Jove and Puck. The stolid German, the vibratile Italian! Yet fantasy wins, even if brewed in a homely Teutonic kettle ... These diabolical variations, the last word in the technical literature of the piano, are also vast spiritual problems. To play them requires fingers of steel, a heart of burning lava and the courage of a lion. [James Huneker]

Michelangeli put together his own sequence of the variations, combining parts of both books. Here's one ordering of them he did: he plays Book One Variations 1-8 and 10-12, then jumps to Book Two Variations 1-2 and 5-8, then plays 10-13 [*No. 12 very lyrical] and 3-4 [No.4 a languorous, delicious waltz in A major in which ABM's legendary froideur melts], and concludes with Book One 13 [ ABM produces some remarkable, feathery-light glissandos in 1948 recording] plus an abridged 14 (i.e. the second half of it).

Suas gravações jamais foram versões do fato, mas sempre a pura verdade do que era capaz. Como raras agulhas de um palheiro exposto nas lojas de disco. Sua versão das “Variações Brahms-Paganini” deveria ser a bíblia dos pianistas. O “seu” “Scarbo", de Ravel, foi o mais sobrenatural da história do piano. Aquele ao vivo e sem edições, em 1986, no Barbican de Londres. As pessoas se entreolhavam e a mesma pergunta se repetia em todos os olhares:

- Será que eu estou ouvindo certo? Ou é simples alucinação?

"His recordings were never versions of the facts, but always the pure truth of what he was capable of. Like rare needles in a haystack displayed in record stores. His version of the 'Brahms-Paganini Variations' should be the bible for pianists. His 'Scarbo' by Ravel was the most supernatural in the history of piano playing. That one, live and unedited, in 1986 [1987?], at London’s Barbican. People looked at each other, and the same question echoed in every glance:

– Am I really hearing this? Or is it just a hallucination?"

(Brazilian pianist Arnaldo Cohen, June 1996)

Piero Rattalino (pp.50-52):

One might suppose that in 1948 Benedetti Michelangeli had to make some cuts to fit within the 78 rpm recording time. The performance recorded in Arezzo on February 12,

1952, however, tells us that this assumption is incorrect: Benedetti Michelangeli restores the ninth variation of the first series in Arezzo but again suppresses the ninth of the second series, makes the same shifts, performs the fourteenth variation

of the first series but not the first part of the finale. In Warsaw, on March 3, 1955, he maintained the same structure as in Arezzo, removing the fourteenth variation from the first series, and thus returning, for this detail, to the 1948 version. In Lugano, in 1973, he adopted the same solution as in Warsaw, eliminating, in addition to the ninth, also the eleventh variation from the second series. In 1988, in Bregenz, I heard the sequence closest to Brahms's: lacking the ninth variation from the second series and concluding with the fourteenth variation and the complete finale from the first series. All these versions seriously compromise, in my opinion, the formal balance of the work, which, moreover, in the 1948, 1955, and 1973 performances, appears truly incomplete in its conclusion.

Now, the only reason I see for the deletions, the only one that seems logical to me, lies in the refusal to face the risks of the first part of the first finale and the entire second finale (the ninth and fourteenth variations of the second series are not difficult). I cannot believe that Benedetti Michelangeli could not, in private, execute with his own skill the

repeated notes of the first finale and the leaps of the second finale.

Evidently, however, Brahms's "piano perversions" (I say this paraphrasing Alfred Brendel) robbed him in public of the margins of safety he deemed necessary. In the extremely risky eighth variation of the first series, he—in 1948, 1952, 1973, and 1988, but less so in 1955—recovered a few hundredths of a second with a slight distortion of the rhythm (the measure became almost seven-eighth notes instead of six-eighth notes). And I must say that the preparation for the return from the fourth variation of the second series to the

thirteenth of the first is done with diabolical refinement, and

that the 1952 conclusion (the fourteenth variation and the second part of the finale of the first series) is diabolically effective. The public performances of 1952 and 1955 are

even more virtuosic than the studio recording. However, it must be concluded that in the Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Benedetti Michelangeli certainly encountered obstacles, perhaps of a purely psychological nature, which he was unable to overcome and which he did not want to face, risking losing control. The archangel does not become a man, he does not encounter the epic disasters of which Sviatoslav Richter is capable, who throws himself madly into the fire. But I believe that the archangel [=ABM] suffered greatly, being forced to give up.

The last word should go to Trevor Harvey who reviewed the '78 record for Gramophone in July 1949. 'The variations are simply magnificent! So magnificent are they that I only wish they were complete. I gather that Michelangeli has recorded them as he usually plays them at concerts and that he was not restricted at all to 4 sides. But when that is said, there is nothing to be added back to the most unreserved praise and admiration. What a pianist! Technically, the playing is astonishing; interpretively here is a very great musician. I venture to think that the player misunderstands only one variation the 4th of set 2, which is over romanticised and taken far too slowly to give anything of Brahms' direction con grazia.'