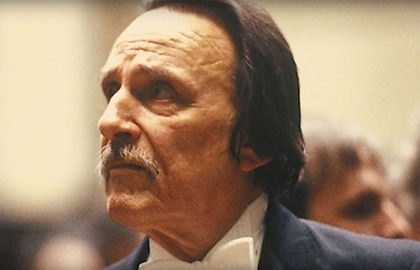

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

Final Years: The Death of a Sphinx

Michelangeli spent years studying the exact

same pieces over and over again. His journey

to Olympus resembles the work of Sisyphos.

In character he was sad, melancholic. His greatest hate was of the adulation of his followers. (Noretta Conci, BBC Radio 3: June 1996).

In 1988, Benedetti Michelangeli had suffered a ruptured abdominal aneurysm during a concert in Bordeaux. After more than seven hours of surgery, he survived.

'It must be said that at his first concert in Bremen, less than six months later,

attentive friends were irritated by his technical insecurity. It would take years for him to regain, as at his last concert in Hamburg in 1993, nearly his former level.' [Cord Garben]

In January 1989, he gave his first concert after his illness (this was in Bregenz). A few months later, on 7 June 1989, he played Mozart concertos Nos. 20 and 25 with the Symphony Orchestra of Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) conducted by Cord Garben.

And in that same month, on 9 June in Die Glocke, Bremen, he made live recordings for DGG of those two Mozart Concertos (No. 20 KV 466 and No. 25 KV 503) with the same forces.

'The Maestro himself, not yet returned to his usual levels, extended some tempos infinitely, in the manner of Parsifal.' [Cord Garben, of the first of the two recordings]

In 1990, he again recorded two Mozart concertos, No.13 KV. 415 in C major [January] and No.15 KV. 503 in B flat [February] in Musikhalle, Hamburg, West Germany.

'Now, having resumed playing, he has once again chosen Mozart. Does this mean that his love for Mozart overwhelms every other musical love? "I love Mozart's music very much, and he left behind a vast and beautiful body of work. Naturally, there are moments of pause, and then you return to this composer more refreshed than before. I'd like to do as much of Mozart as possible before I die."

'In the Concerto in C major KV 503 he plays a cadenza by Camillo Togni (1922-1993) who was also one of his students. "It's the work of a boy written many years ago, but which still seems good to me. It will be a surprise for him too when he receives the record because I didn't tell him anything."

'The Cadenza for the first movement, dating from 1949, still in manuscript form, was sent to Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, at the request of the pianist, in 1959 (see Togni’s letter of 27 April 1959 to Benedetti Michelangeli, Carteggi e scritti di Camillo Togni sul Novecento italiano, Leo S. Olschki (2001)'

Paolo Petazzi

-Nino Rota also wrote something for this concerto.

"Rota wrote something for Haydn's G major concerto. I've often written the cadenzas myself, but I've never said they're mine. Now I'd like to ask Togni, if he's willing, to write the cadenza for the C minor concerto [No.24, K.491]. If I could find a front man, I'd leave my cadenzas, but if I have to leave my name, then I'm not in favour of it.

- But the concert in C minor has not yet been recorded.

"No, it exists. I first heard it thirty years ago in a New York store. I shut down, and the owner went to jail. But it definitely came from Italy."

- You, maestro, played Scarlatti's sonatas in Bregenz after a period in which this composer had been abandoned by pianists. Now it seems things are changing again.

"I've played Scarlatti a lot because I've always tried to broaden my concert repertoire. There are some extraordinary sonatas, which also sound great on the piano, but now that the harpsichord has come into fashion and there are excellent performers, it seems pointless to do it on the piano."

Duilio Courir, Corriere, 1 November 1989

'In Hamburg, a small argument occurred: I was starting the first movement of K.415 rather quickly, because in Kiel I had become irritated by ABM's tendency to drag things out. During the concert, he should have followed me, and I would have kept the desired tempo. In fact, ABM respected my tempo at the beginning of the first movement of KV 415.

When we left the stage at intermission, barely out of sight of the audience,

he threatened me with his finger, like a father who has just caught his son stealing cherries. I truly felt a pang of conscience then, at least until the recording for the album. In

Bremen, the album had already been completely prepared in the recording studio. The Hamburg concert was recorded only as a precaution, without any particular ambitions. When the two recordings were subsequently evaluated, ABM favoured the more spontaneous live recording and rejected the breathtakingly perfect recording of the Bremen "Glocke." I felt rehabilitated for the initial tempo of K.415.'

During the piano rehearsal for the ABM concerts, he was overcome with enthusiasm: "This is a Gavotte (3rd movement, K.503), not a Saltarello." And indeed the movement is a sonata-rondo that opens with a gavotte theme from Mozart's opera Idomeneo, K.367, and which also recalls (apparently) his Concerto for Flute and Harp, K.299/297c. (And on a personal note, how beautifully ABM plays my favourite bars in all of Mozart's concertos, the exquisite passage at 4'10")

'During a visit [of AMB] to my home in Wohltorf, the decision was made, a decision that was fraught with consequences for me: that I should accompany his return to the stage

not only as a producer and friend, but also as the conductor of his concerts. After several performances in Bremen, Kiel, and Hamburg, two Mozart CDs were released with recordings of the concerts. The music world—as his manager Marie-Jose Gros-Dubois said during a subsequent meeting in Hamburg—had rediscovered him thanks to the human commitment and the availability of his producer as a conductor, which made his return to the podium possible.' [Cord Garben]. In interview, Garben said that he thought ABM was actually afraid of "real" conductors. "Er hat hier in diesem Baum [Raum??] deswegen keinen richtigen Dirigenten genommen weil der vor ihnen Angst hatt" (*from the subtitles) Video link

In the Concerto in C major KV 503 he plays a cadenza by Camillo Togni who was also one of his students. "It's the work of a boy written many years ago, but which still seems good to me. It will be a surprise for him too when he receives the record because I didn't tell him anything."

Michelangeli: "I'm reborn" An interview with the great pianist after years of silence:

"I always start from scratch, even with music" says Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli in a gentle voice after patiently allowing himself to be bombarded by the flashes of photographers; we are in a small room in a Hamburg hotel, on the already autumn-coloured banks of the [lake] Aussenalster, where Deutsche Grammophon has organised a tribute to our great pianist on the occasion of the presentation of his latest album: Mozart's Piano Concertos K. 466 and K. 503 with the Norddeutscher Rundfunk Symphony Orchestra conducted by Cord Garben.

Michelangeli, at 69, has always shunned publicity and dissertations on what he has already expressed unmistakably in his playing; But this time the occasion was worth breaking the rules, because it's been exactly a year since the aneurysm that struck him in a life-threatening way in Bordeaux. Now he's looking at a bouquet of flowers he received from France, containing a candle: "I've turned one," he says, smiling, a year of a new life, marked by a rapid recovery and the first concert after the illness, held in Bremen last June and recorded live on the recently released compact disc. Deutsche Grammophon president Andreas Holschneider presents the first copy to the pianist, who, thanking him, says simply, into a German radio microphone that appeared among the crowd: "I think we did a good job."

A series of questions arises. The first concerns the growing spread of pirated records, that is, makeshift recordings, often unbeknownst to the performers, which twenty years after the event can be released in some countries without the authorization of the first interested party; in Michelangeli's case, this has led to outright fakes, labels with his name on bogus content ("I make them look good"). Other questions follow, in which Michelangeli stands out for the objective brevity of his answers...

A German journalist asks Michelangeli how he manages to renew himself when faced with scores he's been performing since his début: "I start from scratch every time; I never pick up a composition from where I left off; I have no memory in this sense; I start from scratch, everything is new, with the emotion of the first time." Then the meeting shuffles around, and the first, more official part is followed by a second, more familiar and rhapsodic conversation. Bremen, Hamburg: why so much familiarity with the German North? Perhaps the audiences in those latitudes have preferable qualities, assuming that some audiences are better than others? "But no, it's not because of the audience; audiences change, my career is now so long that I've seen them transformed on several occasions; Munich, for example, once had a reputation as a rough city, full of Bavarian peasants; today it's perhaps the cultural capital of Germany, the musical life is extremely refined."

He talks again about Camillo Togni's cadenza for the Concerto K. 503, included on the album: "Something from when we were kids [Togni is from Brescia, as is Michelangeli], but it still has value for me, and I've remained fond of it."

(La Stampa 1.11.89)

The Cadenza for the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto, K. 503 dating from 1949, still in manuscript form, was sent to Michelangeli, at the request of the pianist, in 1959.

(Carteggi e scritti di Camillo Togni sul Novecento italiano, Leo S. Olschki 2001, p. 2)

Togni was a favourite student, and later a close friend of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. He attended his classes assiduously from 1945 to 1948—when Benedetti Michelangeli lived with Camillo’s aunt, Esterina Togni in Gussago, near Brescia—then less frequently up until 1953. Togni and Benedetti Michelangeli were linked by a close bond of mutual admiration up until the composer’s death in 1993. Benedetti Michelangeli intended to include Togni’s Seconda Partita Corale (1976) which was dedicated to him, in his repertoire; he recorded Togni’s cadenza for Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K.503 (1989) and he would have performed Togni’s cadenzas for the Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K.491 - a new work for ABM? - in the autumn of 1993 if illness had not prevented him from doing so.

A letter Togni wrote to his composition teacher Franco Margola, dated 16 March 1947, is particularly significant in this regard: ‘I am studying intensely with Maestro Benedetti and this is having repercussions on my composing: I feel an ever-greater need to find fulfilling solutions to the technical-pianistic issues that arise from the foundations on which I believe I base my artistic credo’. As a composer, Togni was aware of the piano’s technical, expressive and stylistic features—developed over a century which can be defined as its golden age—and he was concerned with putting these features to the service of the new language he was in the process of creating: the instrument’s technical fluidity, resonance and expressive qualities were not to be lost. In his music, Togni the pianist developed crystalline, virtuoso keyboard writing—a touching testimony to the influence of the genius that was Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli.

(Aldo Orvieto, English version by Liam Mac Grabhann)

There are two other complete recordings of No.25, K503:

November 19, 1957 in Naples - Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella

- Franco Caracciolo conducting Alessandro Scarlatti della RAI di Napoli

June 26, 1987 in Paris - Salle Pleyel

- Peter Maag conducting Orchestre de Paris Ensemble

«E se ascolto da Benedetti Michelangeli i Concerti di Mozart penso che il suo fervido amore per Mozart, stampato in ogni suono, è come l'amore di Respighi per Monteverdi: l'intuizione di una grandezza incommensurabile, il fraintendimento stilistico più perfettamente coerente. » (Piero Rattalino, From Clementi to Pollini, 338)

And if I listen to Benedetti Michelangeli's Mozart Concertos, I think that his fervent love for Mozart, imprinted in every sound, is like Respighi's love for Monteverdi: the intuition of an immeasurable greatness, the most perfectly coherent stylistic misunderstanding.

His Mozart strikes me as very polished, cold as ice (though flickering into life here and there), and as in an interpretation of important music really not very interesting. The manner is lofty, and the tone, largely declamatory, with the solo part chiselled into high relief, whatever the context; there is little variety of weight or colour. Most of the finale of K.503 in C major suites Michelangeli better; so perhaps does the grandeur of this concerto as a whole with its juxtapositions of large elements, and its Beethovenian emphasis on repetition. He may not play it anymore, subtly than the D Minor, or collaborate more closely with the orchestra, but the scale of K503, and the more neutral character of its material, marry better - it could be said - with his own rather impersonal style.

Stephen Plaistow (Gramophone, July 1990)

'Each [of the four Mozart concertos] is approached from a standpoint almost entirely dictated by the intrinsic character and properties of the piece itself, as seen by Michelangeli at that particular time. Nothing reveals this more strikingly than his use of the piano itself. It seems unlikely that any pianist in history has had a more sovereign control or commanded a wider range of tone colours. The chances of his achieving any quality of sound by mistake are virtually non-existent. Despite his near obsession with sonority, he was too scrupulous a musician to cultivate it for its own sake. His reasoning and convictions were not always easy to understand, but given the artistic integrity, the tireless intellect and the intense dedication of the man at the keyboard, it behoves us to try. He may persuade us, or he may not, but he demands our attention.' (Jeremy Siepmann)

After the recordings of Mozart’s concertos, Michelangeli returned to concert life completely, - at lest as he understood it - planning to perform in Bordeaux, Paris, London, among others, and during a small celebration organised for the release of a new CD with Mozart’s concertos in D minor K 466 and C major K 503 117 he declared: “I am returning to my duty, music”, and further that “I dedicate the rest of my life to Mozart”, but he will not abandon his “eternal loves, Beethoven, Liszt and Grieg.”

10 May, 1990: Barbican Hall, London, England

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, Op.111

Chopin: Scherzo No.1 in B minor, Op.20, Mazurka in B minor, Op.33 No.4, Andante Spianato & Grande Polonaise Brillante, Op.22

13 May, 1990: Barbican Hall, London, England

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.11 in B-flat major, Op.22, No.32 in C minor, Op.111

Chopin: Scherzo No.1 in B minor, Op.20, Mazurka in B minor, Op.33 No.4, Andante Spianato & Grande Polonaise Brillante, Op.22

'Beethoven No.11 was dispatched with seeming indifference and No. 32 with cool dispassionate mastery. The great Mazurka in B minor, Op.33 No.4: 'wonderous inflections, no trace of dance'. (Musical Times, August 1990)

Munich

In June 1992 ABM held a series of memorable concerts in Munich, accompanied by the Münchner Philharmoniker conducted by his old friend Sergiu Celibidache - a friendship dating back to at least 1942 - on the occasion of the Romanian conductor’s 80th birthday. It was probably the apotheosis of a unique and unrepeatable career, which would end in Hamburg on 7 May 1993.

There had been a rupture between the two musician in 1980 as a result of events in Tokyo.

'In 1992, the signs pointed to reunification, and the Ravel concerto was scheduled. For days, ABM practised, listened, and tinkered for hours alone in the Philharmonie.

Outsiders are not permitted into the hall, even Celibidache doesn't show his face. No meeting, nothing. Sometimes the two sit next to each other, but neither opens the door to the other. Only at the official start of the rehearsal do they meet with cordial coolness. Celibidache: "Carissime!" Benedetti Michelangeli is silent. For the time being, not another word is spoken, nothing personal, nothing about the performance of the work. But the ice is broken, and it melts when ABM gulps astonishing amounts of Dom Pérignon with his old friend at the Hotel Rafael (now the Mandarin Oriental, Neuturnmstrasse 1).

'The Ravel rehearsals are calm and focused. The middle movement, which begins with the long, slow piano solo and only brings the orchestra in later, with a gossamer web of sound, is a magical success. Celibidache: "I'm always afraid to enter with the orchestra." Am I not ruining everything he conjured? Nothing is ruined, the magic remains.

'But a scandal ("ein Eklat") looms at the first of their four joint performances. Sony wanted to videotape the performance; during rehearsals, all picture and sound settings were fixed, and all lighting details were determined. But someone must have changed the fixed values later. Who, and whether intentionally or negligently, remains unclear. Apparently, the Sony people found the lighting too dim on the first evening, so they switched things.

'When the two stars finally came onstage together for Ravel (2nd evening), the spotlights blazed mercilessly from the ceiling. Benedetti Michelangeli immediately felt irritated:

"I can't play like this," he said, even more deadly serious than usual, "me ne vado" - I'm leaving. Celibidache: "I must have looked like a small child dying or losing his entire family."

'Benedetti Michelangelo stayed. "It's fine," he said quietly, looking even more distressed than usual. If it hadn't been for the joint performance with Celibidache, the pianist, as he subsequently insisted several times, would have left. Celibidache constantly waved his baton during the first movement to draw the attention of the Sony technicians to himself and his protest. Finally, the glare was turned off during the performance, and the recording was aborted. The recording was canceled, and Benedetti Michelangeli immediately canceled the solo piano recitals scheduled for the following Whitsun weekend in Munich.

' "Magic of Perfection," the Süddeutsche Zeitung celebrated the event; 'Ein Wunder" the tz judged. Celibidache a few weeks later said: "It wasn't so great. He started late a couple of times. What was that? I wasn't used to that from him. His hands were shaking terribly.'

'While the Gasteig audience is still applauding vehemently, a chair is carried onto the podium on all four evenings. "Homage to the eighty-year-old maestro," the first concertmaster explains the procedure to the audience, a few days after the maestro's eightieth birthday. A touching encore: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli plays a birthday serenade for his old companion. Before that, there are long, momentous minutes of concentration, as if the well-wisher couldn't think of anything to say, then Chopin mazurkas, Debussy's Hommage à Rameau,... It was almost a private evening in front of 2,300 guests. What no one suspects in this beautiful evening moment: the closest and most lasting relationship Celibidache has ever had with a musician ends.'

(Klaus Umbach, 1995)

In the film Beyond Perfection, Michelangeli is said to have - incorrectly - blamed Cord Garben, his producer and collaborator for 17 years (1975-1992), and the morning following the lighting disaster, demanded an apology from him via his management. When one was understandably not forthcoming, Michelangeli broke off the contact completely.

5, 6, 8, 9 June , 1992: Munich, Germany

Ravel: Piano Concerto in G major

– Sergiu Celibidache / Munich Philharmonic Orchestra

Encores: Chopin: Mazurka in G minor, Op.67 No.2/ Chopin: Mazurka in B minor, Op.33 No.4; Debussy: Reflets dans l’eau (Images, Book I No.1), Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut (Images, Book II No.2), Hommage à Rameau (Images, Book I No.2), Grieg: Lyric Piece in E major, Op.68 No.5 (Cradle Song).

Friedrich Edelmann, Munich Philharmonic's principal bassoonist for 27 years, said that during 2 weeks of rehearsals (1980/ 1992?), Celibidache had advised the members of the orchestra not to smile, laugh or talk as this would upset the pianist - this might 'distract him or cause him some turbulence'. Michelangeli arrived with two pianos, which he alternately tried out. But the hall was too moist (the Deutsches Museum being next to the River Isar). The pianos were taken to the cellar, and the technicians worked on them throughout the night, drying every key. Celibidache and ABM stood there, watching them! Work was finished at 4am. Pianist and conductor, then walked in the Englischer Garten, and when they got hungry, Michelangeli roasted a duck in his apartment (he apparently always demanded a kitchen in his accommodation).

(Edelmann's book Memories of Celibidache is only available in Japanese)

'With remarkable humanity, Klaus Bennert, in the Süddeutsche Zeitung of September 28, 1992, noted that in the old Milan recording from 1942, "the furious stretta effect at the end of the first movement is still electrifying." It was part of the tragedy of perfection "that in certain respects it tolerates no alternatives." Whenever even the slightest flaw crept in, for Michelangeli the world of art was no longer intact.' [Cord Garben]

Duilio Courir, who heard the particular concert which also included Rossini's Semiramide Overture and Mozart's Haffner symphony, wrote in Corriere della Sera on 7 June:

'The measure of an ideal relationship with Michelangeli, albeit with different roots, was heard in Ravel's Concerto in G. Ravel's invention in this score, attentive to his American experiences, does not hold him back from that sharp, Goya-esque illumination of things, from that refinement of timbre that seems to open the way to the liberation of sound and which seem inseparable from Michelangeli's teachings. Nothing has changed in this musician, but today it seems clearer than ever that the legitimacy of modernity cannot be separated from his teachings. In short, it was a marvellous evening, greeted by the audience with a veritable frenzy of applause.'

"Thus, Celibidache and Benedetti Michelangelo set off on their Far Eastern journey. The announcement triggered a presale record in Japan, and prices rose to the equivalent of 365 marks; in just under forty minutes, all tickets were sold out. 'It goes without saying that Michelangeli tickets in Tokyo were traded like a rare drug among addicts,' reported Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from the Far East.'

Japan, October 1992

'Not even the one great relationship spanning a long human life lasts: Celibidache is over eighty, Benedetti Michelangeli over seventy, when this friendship too breaks up—quietly, as if by chance, apparently for good.'

'On 26 September, 1992, the two, after months of planning, rehearse for their joint tour of Japan: Robert Schumann's A minor concerto. No work connects them more closely. Munich, Gasteig. Celibidache accompanies extremely reservedly, almost a little indecisively, as if, for God's sake, he doesn't wants to endanger anything and unsettle anyone. Benedetti Michelangeli falls unmistakably short of his former solitary mastery: Eusebius and Florestan display a senior-like moderato, the upswing is stunted, the reverie strangely distant – everything is classically restrained.'

(Klaus Umbach)

A summit meeting [ein Gipfeltreffen] of difficult grandmasters... that everyone wanted to witness and paid exorbitant black market prices for the last tickets. And afterwards? asked Klaus Bennert in the prelude to his review in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, subtitled with the apt, apt line: The tragedy of perfection. (Other items in the Munich programme were Berlioz' Roman Carnival and Prokofiev's fifth symphony in B flat major)

'Thus, Celibidache and Benedetti Michelangeli set off on their Far Eastern journey.' The announcement triggered a presale record in Japan, and prices rose to the equivalent of 365 marks; in just under forty minutes, all tickets were sold out. 'It goes without saying that Michelangeli tickets in Tokyo were traded like a rare drug among addicts,' reported Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from the Far East.

'A week before his first performance, Benedetti Michelangeli had already entered a seclusion with his piano tuner to drill himself into peak form and perfect his instruments accordingly. Apparently, the result fully met the expectations of the Tokyo audience: 'In any case, both maestros,' writes Manfred Osten in the FAZ, 'succeeded in putting their listeners into a hypnotic state that lasted even after the last chord of the piano concerto, only to then erupt in frenetic applause and a standing ovation.'

The critics on site, however, are less in a hypnotic state than in a wide-awake, extremely alert state. 'We missed, from both maestros, the energetic performance we had actually expected,' writes the critic of Yomiuri Shinbun, and H. Iwai summarises in Mainichi Shinbun under the heading 'The musical energy is dwindling' and more harshly:

'We must accept these slow tempos and dull rhythms because the two are eighty and seventy-two years old. In the past, they radiated a sense of bliss... I have a bad feeling about the aesthetics of the two old people....'

15, 16 October, 1992: Showa Women’s University (Hitomi Memorial Auditorium), Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan

Schumann: Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.54

– Sergiu Celibidache / Munich Philharmonic Orchestra

Listen to Schumann on 16 October

28 October, 1992: Suntory Hall, Tokyo, Japan

Chopin: Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op.45; Piano Sonata No.2 in B-flat minor, Op.35

Debussy: 12 Preludes (Book I).

A comment on YouTube says that Chopin's Andante Spianato (G major) & Grande Polonaise Brillante in E flat major Op. 22 were played at the end of first half of this recital (before intermission and immediately after the Chopin Funeral March Sonata) and this is confirmed by the Suntory Hall website archive. Listen to the recital

Break-up

On 5 October, 1992, Corriere della sera printed, under the heading "Spettacoli," an interview with Celibidache, conducted in Munich before the tour began, about the Italian star pianist and artist friend Benedetti Michelangeli.

'He, Celibidache, is frightened by his partner's endless loneliness. The question: Where did this loneliness arise? Answer: From the absence of a human heart in his life. Sometimes he changes completely. If, for example, he particularly likes a woman, he becomes a different person—full of wit. Then he talks, is brilliant, and highly entertaining. Question: Did you visit him in Lugano? Answer: Yes, he lives a simple, sometimes strange life there. Once, he shivered from the cold all winter long. But when I returned months later, I found the house surrounded by three-meter-high piles of wood, all preparations for winter. For all the wood, you couldn't even find the entrance.'

With this trifle, a revelation the size of a footnote, a tacit agreement that had lasted more than half a century seems to have been broken—Benedetti Michelangeli, the hermit behind the wooden wall, sees himself and his privacy criticised.

The most reliable, most discreet friend has, needlessly, lifted the curtain and given the multimedia gawkers a glimpse into the other's intimate sphere: "He truly needs," Celibidache is heard to say, "a person who loves and appreciates him and who doesn't criticise him." And the reader must assume that this person doesn't exist.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli is disappointed and annoyed. He signals that he considers the human and artistic partnership to be over: no more joint concerts, neither in Munich nor on tour. Attempts at repair undertaken by Celibidache's entourage remain unsuccessful: the petulant maestro cannot bring himself to make a gesture of reconciliation, and the letter that could perhaps undo the feud remains unwritten.

In June 1980, Renzo Allegri had interviewed Dr Arnaldo Lenghi, a long-standing friend of Michelangeli since they were boys.

"I know the maestro doesn't like people talking about him," Dr. Lenghi told me, when I met him at his villa in Ponteranica, on the outskirts of Bergamo. "But I don't think it's right to remain silent always, allowing so much nonsense to be written about him that has no basis in reality."

-During his life, the maestro has not been very fortunate romantically: why?

LENGHI: It's hard to know. He has always been admired and courted by women, from a very young age. It's not easy living with the maestro, but it's not impossible. Women probably think he leads a brilliant, imaginative life, with parties, salons, and luxury. They don't imagine, however, that his is a Carthusian existence. Perhaps this is the cause of his romantic failures.

Earlier in the interview, Lenghi had said: 'He's a man who struggles to communicate. He sends a few postcards. Letters are very rare. When he writes a letter, it means it's something very important, and who knows how much he thought about it before writing it. In all the years we've known each other, I've received several postcards and telegrams from him, but only one letter. He sent it to me a few months after he spent time at my house treating his back. It was a very difficult time in his life. We had very tactfully made him understand that our home was always there for him. He wrote to me: “Dearest Nando, I don't feel like saddening you any further with my presence. I have upset and disturbed you too much by so peremptorily invading your family serenity, and I apologize. I am now in a very painful period of my life and can only spend it in solitude. My feelings of gratitude and blessing for what you have been able to do for me, which no one else has been able to do, will always accompany you.”

Farrago, confusion, what's going on...?

1992 was Benedetti Michelangeli's final visit to Japan. He was scheduled to perform two collaborations with Celibidache and three recitals. While he performed his collaboration with Celibidache and his first recital as scheduled [28 October?], the venue and date of his second recital was changed, and the third recital was cancelled. There were plans for another visit to Japan the following year, in 1993, but his doctor ordered him to stop performing due to a worsening of his chronic heart condition, and the plan was scrapped.

(Japanese Wikipedia, unsourced)

'The Michelangeli concert on 19 [?] October, 1992 was held at the Hitomi Memorial Hall, which we had thought would be a good October performance with low humidity, but

it was met with a downpour that began in the evening. The piano, tuned in an air-conditioned and humid environment, must have been in perfect condition to the artist's satisfaction. However, as the audience entered the auditorium in drenched suits,

the humidity rose immediately, and the condition of the piano likely changed. The artist requested a change in the venue for the next concert, but was dissatisfied and cancelled the remaining concerts.' [Amazon Japan review]

'Michelangeli's recital at Suntory Hall on November 1, 1992, was cancelled just before the scheduled performance date. As I recall, the concert was scheduled to begin at 12:30 p.m. on a Sunday, but the doors were delayed from opening at 12:00 p.m., and the cancellation was announced around 12:45 p.m., but since it was so long ago, I'm not sure. In fact, the concert had been scheduled for Hitomi Memorial Hall much earlier, but the date and venue were changed to Suntory Hall.'

'While I adore Schumann's magnificent concerto, I wanted to take this rare opportunity to focus solely on Michelangeli's music. I wanted to listen solely to Michelangeli's exquisite piano playing, uninterrupted by any other sounds. On the day tickets went on sale, I visited the Kajimoto Music Office in Ginza early in the morning and joined the queue of passionate fans. It was a Saturday, late in the morning, but the long queue had already formed in the corner surrounding the Kajimoto Music Office building, creating an eerie scene.'

'A year later, in the autumn of 1993, it was announced that Michelangeli would be coming to Japan again. The dream would be realized once more. Japanese audiences were eager for this, and I believe Michelangeli himself wanted to visit Japan again and rediscover himself. This time, I was extremely excited, as his All Debussy concert in Hamburg in May 1993 had been extremely well-received, rumored to be close to Michelangeli's former peak. Since I had missed the 1992 concert, I was able to secure tickets through a special ticket sales. Two programs, totalling four concerts, were scheduled, but learning from my experience the previous year, I decided to choose the earlier dates for both programs. The program consisted of all Debussy and a selection of works by Beethoven, Brahms, and Chopin. As Michelangeli enthusiasts will know, these were all pieces that Michelangeli had been confidently performing since his youth, and had long considered his favorite repertoire. For me, the most anticipated piece was Debussy's Preludes, Book 2, which was a wonderful selection. However, Michelangeli's health continued to decline, and his doctor advised him not to perform, which would have involved long trips.'

(from the Japanese, found on tsukimura.art.coocan.jp)

Curioser and curiouser...

His beloved mountain, the two huts in Rabbi, the village in Val di Sole, in southern Trentino. Sold at the end of 1992 for a considerable sum: but the maestro, it has always been said, died in poverty, after also selling his house in Pura, Switzerland. Someone—ridicule is always lurking—dared to compare him to St. Francis. Now, every word pains her [his widow Giuliana BM, née Giudetti], and as she recounts the story, she struggles to visualise what she is saying, because she was not there on November 9, 1992.

Other trusted eyes saw it and told her: “On the day of the move from Rabbi, he was heartbroken and shouted, ‘Go away, get out of my way, or I'll start the car and run you over,’ at a lady, his last secretary, who was rushing him. He didn't want to leave, but they took everything away, even the trunk of our memories, which Ciro had always kept with him.

”Why were the rolls of film taken by the dentist who had gone to visit him in Pura confiscated? Why did cardiologist Umberto Rabagliati tell her on June 12, 1996, a year after his death, “You can't imagine how much they made him suffer”? Why did the master reveal to Isacco Rinaldi, the pupil he loved like a son he could never have, while pointing to the garden: "Now I'm going to build a shelter for myself above those chestnut trees, because they threw me out of the house here?"

Sandro Cappelletto, La Stampa (12 June 1997)

Final recital

'His sharp, constantly suppressed, almost insidious gaze, his head always cautiously turned, gave the impression of a man who constantly listened to his inner voice. You could believe him when he said, "I am always working!" He spent his most intense hours in the soundproof room he had installed on the lowest floor, [in Pura] alone with his three black companions: the concert grand pianos.' [Cord Garben]

In May 1993, Michelangeli cancelled four concerts in London due to the organisers' failure to comply with the terms of the contract: this document specifically prohibited the sale of tickets to groups of people, regardless of nationality. When he learned that 85 Italians were to come to London thanks to an "all-inclusive" package offered by an organisation from Bologna, he left London with the explanation: "I am not a tourist attraction". Michelangeli had been intolerant of commercial exploitation and speculation throughout his life.

Corriere della Sera, 18.5. 1993

On the 7th of May 1993, he nevertheless gave a recital in the Hamburg Musikhalle, which became the last concert of his career. “The perfect Michelangeli, who worried that not even a single eyebrow would move while playing when he was being recorded by cameras during his concerts, in Hamburg, where he had played many times, he would start singing while he was playing.”

Roberto Cotroneo, Il demone della perfezione. Neri Pozza editore, 2020

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli's final recital (he canceled some concerts in London)

7 May, 1993: Musikhalle, Hamburg, Germany

· Debussy: Children’s Corner (Suite)

· Debussy: Images (Book I)

· Debussy: Images (Book II)

· Debussy: 12 Preludes (Book I)

'First of all, [in this recital] Michelangeli does not have the usual, impeccable, controlled posture to which his audiences have become accustomed and which has become a fundamental part of his iconography. This time he moves, "opens" his gestures, raises his hands from the keyboard, as Gian Paolo Minardi recounts (his recollection of that day is found in Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli's book Il suono ritrovato), but he does more, and it's unheard of. He sings. The audience groans during the performance. Some are outraged because someone in the audience apparently isn't respecting the order of silence, and yet it's none other than him, the austere Michelangeli, who sings. (Bruno Giurato)

In June 1995 he was admitted to the Cantonal Hospital in Lugano after suffering another heart attack. He died during the night between 11th and 12th June. He was buried in the small cemetery in Pura, in a very simple grave which, in accordance with his wishes, is without a headstone.

He requested a modest ceremony, attended by one hundred and fifty people, including Martha Argerich and Maurizio Pollini, also his piano tuner. He was buried in bare ground and asked for a wooden cross instead of a tombstone.

Carlo Maria Giulini, the great Italian conductor who collaborated with ABM for a long time, after his death declared: “I can tell you who the pianist was, but who the man was remains a mystery. An almost insurmountable barrier separated the artist from the man, imprisoned by his personality. […] We always remained a bit of strangers when we worked. I never once saw a smile light up his face, and even worse, in the darkness of his face you can see how much he suffered. It seems that you, Arturo, lived in darkness, except for the moments when you played the piano. At that moment, it was you who gave people this joy and this light that you perhaps lacked and which you are missing and which you have now perhaps found.”

Roberto Cotroneo Il demone della perfezione

Mysterious In Death As In Life

After a life of indifferent health, Michelangeli died in Lugano on 12 June 1995 aged 75. Even his death is shrouded in mystery. The doctor who attended him requested anonymity and said that the pianist had asked him to keep the cause of his death secret, though most say he died of a heart attack.

Há um conto de Henry James que serviria bem de comentário à carreira de Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. Neste conto ("The Coxon Fund'', nunca traduzido), a personagem central é um filósofo, baseado no poeta romântico Coleridge, que, embora reconhecido por seus amigos como o maior gênio da era, jamais comparece às palestras que deve dar, e só raramente chega a escrever suas idéias no papel.

'There is a short story by Henry James that would serve well as a commentary on the career of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. In this short story ("The Coxon Fund," never translated into Portuguese), the central character is a philosopher, based on the Romantic poet Coleridge, who, although recognized by his friends as the greatest genius of the age, never attends the lectures he is supposed to give and only rarely writes his ideas down. Michelangeli, who died last week at the age of 75, was a pianist of canceled concerts and infrequent recordings.'

Arthur Nestrovksy, obituary of ABM in the Brazilian newspaper Folha, 26 June 1995

Giuliana Guidetti Benedetti Michelangeli - his widow (they separated in 1970 but didn't divorce) died on 12 Apr 2015, aged 94, in Villanuova sul Clisi, Provincia di Brescia, Lombardy, Italy. Marie José Gros-Dubois, his companion and secretary (20 years younger than he) ... Her brother Bernard had been born in Ste. Marie, Martinique, French West Indies.

Envoi

'[Michelangeli's long-time secretary and partner] Marie José Gros-Dubois accuses the media: "Stop talking about the black handkerchief he placed on the piano, stop saying he wore an antique tailcoat to concerts, and stop with the nonsense that he destroyed three pianos a year playing them so much. I want the truth. He was good, he loved clean things. Why do you enjoy saying he canceled concerts at the last minute? If he canceled them, it was because he knew he couldn't perform, it was because he respected the audience. It wasn't a whim. How much anguish I felt! He was attacked and couldn't defend himself, he never gave an interview. Give him the truth now."

She recalls: "In his last letter, the Maestro said: 'If you want to do something for me, stop the piracy of records.' How can anyone think that someone who worked at the keyboard for seventy years would be robbed of a concert? Robbed of technical fidelity, of study, of effort, of passion. They even stole the rosary I had placed between his fingers in his coffin."

Paolo Mettel, president of the Cotonificio Olcese and a friend of Benedetti Michelangeli, also says it's time to move away from the flowery tales. There is a truer, more secretive Michelangeli. The one of his invisible days in the rented house in Pura, the village above Lugano where he had lived since 1979. "Days marked by detachment, simplicity, spirituality," says Mettel. "Music is the most abstract art, the most distant from reality: those who cultivate it also abstract themselves, practising an asceticism. So did the Maestro, to the utmost degree. A seemingly bare life, his."

Michelangeli could get up very early, even at four. Or late, if he had studied hard during the night. He would immediately go to one of the three pianos in the sound-proofed studio: "For him, a concert was not a performance but the result of tireless and never perfect work on an composer." His only distractions: a cup of Japanese tea, scented or smoked; a caress, a game with Attila the cat, a stray; a walk in the park and the orchard, among the cherry and apricot trees. He had no children: he liked children: "He joked with my children," Mettel recounts. "He would pretend to steal a slice of cake from them, as if he wanted to eat it himself."

He relaxed with friends: "He would discuss Formula 1, compression ratios, and carburettors, with the same expertise he showed the action of a piano. He appreciated Niki Lauda because he was also a great tester. It was he, the Maestro, who suggested to his tuner Angelo Fabbrini the B flat he wanted. He even persuaded Steinway to modify some parts of the pianos they produce, and Steinway in Hamburg kept his two concert grands."

"Let's erase the falsehoods," says Don Antonio Sfriso, 88, in a retirement home in Sonvico, a few kilometres from Lugano. "I was his confessor, I was his friend for twenty years. We often ate together. Last Sunday, a few hours before the end, he couldn't wait to enjoy my niece Bice's chiacchiere [fried sweet pastry]. Michelangeli was a man of little food. It's not true that he was a vegetarian; he had no passion for meat, that's all. He tasted everything. He even cooked, and he didn't want anyone around. When he taught, he was the students' chef. He made an excellent roast chicken. He drank a glass of wine, and to finish, he smoked Tuscan classics...

Don Antonio recounts: "Michelangeli suffered from his character. He was proud, aware of his art, but also shy. He couldn't stand being admired... He was often confined to bed by illness; he had several bypasses. I sat next to him in his room, white as a cell. One early morning I went to visit him: he was awake, on the bedside table he had a book on the Novissimi, the mysteries of the Afterlife: 'These thoughts,' he told me, 'instil in me the nostalgia of arriving where my heart has longed to arrive.' Dear friend, you are there."

He will be buried in Pura, ten kilometres from Lugano, where he had lived since 1972 in a small house among oak and chestnut trees. No one ever saw him. A music critic, Vittore Castiglioni, lives in Pura: "In all these years, I've only met him twice," he says. "One morning he was standing next to his house, staring grimly into the woods. Another time he drove past me, and I just had time to catch a glimpse of his black moustache and black sweater. He had his piano in tow, hoisted inside an enormous case on a small trailer." He wouldn't let anyone get close. He was in exile everywhere, or perhaps everywhere was his homeland because—he said, remembering Seneca—everywhere he could see the sky.

La Stampa, 13 & 15 June 1995