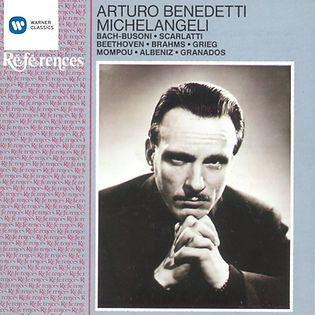

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

Competitions

1936-1939

Michelangeli was placed second in two national competitions, in Genoa in 1936 and in Florence/Firenze in 1937. In May 1938, at the age of eighteen, he began his international career by entering the Ysaÿe International Festival in Brussels, Belgium, where he finished seventh. (It was originally called the Eugène Ysaÿe Competition but adopted its current name in 1951 to honour Queen Elisabeth)

Emil Gilels took first prize and Moura Lympany second.

Gilels, born in Odessa in 1916, graduated from the Odessa Conservatory in the autumn of 1935. Subsequently, he was accepted into the class of Heinrich Neuhaus as a postgraduate student at the Moscow Conservatory (1935-38). 'Upon arriving to Moscow at the start on 1936, the great conductor Otto Klemperer performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor Opus 37 with none other than Gilels as the soloist. In the wake of this performance some members of the conservatory found it ‘a first-year student performance.’ Yet writing later, Neuhaus reported that it was an ‘outstanding performance’ in which he ascertained structural integrity, truth and simplicity.'

[Emil Giles Foundation website]

The 1938 jury included Robert Casadesus, Ignaz Friedman, Walter Gieseking, Léon Jongen, Arthur Rubinstein, Emil von Sauer and Carlo Zecchi.

'As always happens in these cases, since the superiority of the twenty-two-year-old Gilels could not be disputed, the other positions were contested. Many critics believed that the eighteen-year-old Benedetti Michelangeli had been penalised, and it was even insinuated that the Italian juror Carlo Zecchi had given his compatriot a very low score (jealousy of the rising star?) The second-place finalist, the English woman Moura Lympany, recounted that Benedetti Michelangeli had encountered serious difficulties with the Piano Concerto No. 1 Op.30 by Jean Absil, unpublished, lasting about 14 minutes and "exceptionally compact", which the 12 finalists had to perform after two weeks of study [*but see below]. Arthur Rubinstein, who was part of the jury, says simply that "Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, the famous Italian artist, gave an unsatisfactory performance at the time, although he already showed that he possessed an impeccable technique"' (Piero Rattolino)

The Brussels periodical Dernière Heure on 19 May, 1938, described the first selection of the competition as follows: 'An Italian caused a great shock: Maestro Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, born in Brescia in January 1920. A perfect virtuoso, he played J.S. Bach’s Italian Concerto in beautiful style. He unleashed all the elegant finesse of his race in Scarlatti's Sonatas, but he was even more surprising in the Bach-Busoni Ciaccona,

performed with a majestic grandeur, a magical sonority, reminiscent of the school of his illustrious compatriot Ferruccio Busoni.'

In the final on 29 May, 1938), ABM played:

Edvard Grieg, Concerto in A minor op. 16

Giuseppe Martucci, Thème avec variations

Fryderyk Chopin, Scherzo n. 2 in B flat minor op. 31

Fryderyk Chopin, Etude in C sharp minor op. 10/4

Claude Debussy, Reflets dans l'eau (Images I)

Franz Liszt, Polonaise n. 2 in E major

Charles Scharrès, Scherzo Fantastique

The Orchestre Symphonique de l'INR [= L'Institut national de radiodiffusion/ Nationaal Instituut voor de Radio-Omroep] was conducted by the Belgian Franz André

In her autobiography, Moura Lympany writes: 'We 12 young pianists, where each allotted a room with a piano in the magnificent royal palace of Laeken for one whole week leading up to the finals.' They had to learn by heart a new concerto by Jean Absil which had been kept secret up until then. 'Michelangeli practised eight hours or more a day, an excessive amount' and his hands seized up, requiring medical attention.

In the June 1938 review of the competition in the magazine Le Flambeau, we find the following observations: 'This final ranking doesn't fail to amaze us; in reality, it has satisfied no one.' The magazine suggests the judgment of a noble Hans Sachs—'as is well known from Wagner's Meistersinger'—was required rather than the hair-splitting criticisms of a Beckmesser, which were the object of ridicule among the people of Nuremberg. 'This would be the best way to find the truth.' Le Flambeau concluded by publicly expressing what many were thinking: 'Maestro Benedetti Michelangeli's ranking seems almost unfair to us. Rivalry between schools or what else? It could be.'

Giuliana Benedetti Michelangeli recalls the rumours that spread at the time. Rumour had it that an Italian member of the jury [Carlo Zecchi], a renowned pianist, had awarded ABM the lowest score. This decision may have been motivated by regret that three of the Italian pianists supported by this juror, fresh from brilliant results at the major Vienna Piano Competition, had already been excluded in the preliminary selections. [Cord Garben]

A Russian correspondent (August 2025) has provided this additional information:

'A new biography of Emil Gilels was recently published (author - Elena Fedorovich.) In this book, you can find a fragment of the pianist’s memoirs about the 1938 Brussels Competition:

“We were housed,” Gilels said, “in a country residence of kings under the supervision of a certain gentleman. He made sure that we did not communicate, that we each studied in our own room and followed a single daily routine. You know, we were hungry all the time, even our mood dropped because of it. The food was exquisite, but in small doses, and I dreamed of Ukrainian borscht. Yasha Flier and I got up at night and quietly rummaged through the buffets to get something edible. Unfortunately, we found nothing but cookies. Then other laureates, guys from different countries, followed our example.

We also violated the regulation that prohibited communication."

'On the fifth day of this peculiar seclusion, Emil, according to him, realised that he hadn't even begun to analyse that test piece (the Concerto by J. Absil, written especially for the competition, which the finalists were given a week to master): "Some unusual musical notation!"

- One evening I suddenly heard, - he continued, - an Italian boy behind the wall already playing this composition at a fast pace. I made my way to him and said: "Show me where you started." He's a nice guy, he started showing and explaining something, although at that moment I realized that there was nothing tricky here, it was just general fatigue taking its toll. I went to my room and immediately got to work..."

"The nice Italian boy" from whom the future undisputed winner "asked for help" was 18-year-old Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, who took 7th place, but entered the elite of world performance.

'My personal clarification: this recollection differs significantly from what Lympany says (about Michelangeli's difficulties with the Absil concerto). There are other inaccuracies in her story about ABM. But I am just getting acquainted with these materials.'

Benedetti Michelangeli took his revenge a few days later with the triumph in a recital held in Brussels on June 15th. La Dernière Heure on June 17 insists on arguing with the jury:

"Benedetti Michelangeli's recital had sold out in the small hall of the Palais des Beaux-Arts (...) It is evidently indiscreet to criticise the award of the prize by a jury composed of so many eminent masters, but according to the opinion of many it seems evident that Michelangeli did not obtain the placement he deserved and the jury showed itself too demanding towards him. But all this is past, it is history. (...) Enormous success, triumphant".

In De Standaard on June 18, 1938, signed by M. Boereboom:

"The recital - one of the few to which dozens of enthusiasts had to renounce for lack of space - revealed a great artist (...) He does not act like a "tamer of sounds" of Herculean power; he is above all a musician who knows the secret of the sensual creation of sound and lets his Italian temperament shine through in the sought-after and undulating melody and in the clarity of his nuances. He does not lack energy, but he achieves technical perfection without conspicuous efforts; technique and expression flow naturally together. The performance was beyond all criticism in the Italian gallant music of the 18th century by Paradisi, Grazioli and Galuppi. (...) We were amazed by the solar virtuosity of the Prélude n. 16 and the Etude op. 10 n. 4 of Chopin; the almost impossibly fast tempo did not bring the slightest confusion, nor the slightest rhythmic complexity."

Antonio Armella, I Concerti di ABM (2025), 20

A year later, in 1939 (the year of its foundation) Michelangeli won first prize in the Concours de Genève/Geneva International Music Competition, where he was acclaimed as "a new Liszt" by pianist Alfred Cortot, a member of the judging panel, which was presided over by Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

8 July, 1939: Geneva Conservatory [?], Geneva, Switzerland. The Winner’s Concert was broadcast on radio.

Liszt: Piano Concerto No.1 in E-flat major, S.124

– Ernest Ansermet / Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Career beginnings

Upon winning the competition, Benito Mussolini gave Michelangeli a teaching position at the Conservatorio Giovanni Battista Martini in Bologna, Italy. He was the youngest of the teachers but also the most famous. He did not shy away from making himself personally known in the city, and on 5 January, 1940, he performed in the concert season organised by the school.

Michelangeli could have attended the advanced course taught by Alfredo Casella at the Santa Cecilia in Rome. In Tremezzo, on Lake Como, there were summer courses taught by Artur Schnabel. But he attended neither. Culturally, he was behind the times.

(Piero Rattalino)

Monday, 28 February 1938: This evening, at 9:20 pm, at the Conservatory (his very first concert in Milan), the Friends of Music will hold their ninth social concert, conducted by the very young pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. The programme includes music by Bach-Busoni, Paradisi, Grazioli, Galuppi, Chopin, Martucci, Respighi, Riccardo Pick-Mangiagalli, Debussy, and Liszt. His technique is often dazzling, so much, so that it is the envy of many pianists who have had years and years of practice and performance under their belt. (Corriere della Sera). The piece by Ottorino Respighi is said to have been the Notturno in G flat major from his Sei Pezzi per Pianoforte P.044 (here played by Konstantin Scherbakov in 1997). Scherbakov also plays the delicious Antiche danze ed arie per liuto P. 114: VIII. Bergamasca

Friday, 10 November 1939, Teatro del Popolo, Milan. Recital including Brahms-Paganini.

Vladimir Horowitz played often in Italy in the 1930s, and it doesn't seem unlikely that Benedetti Michelangeli listened to him and tried to imitate him. (Piero Rattalino)

Rome début

6 December 1939, Teatro Adriano, Rome

Orchestra of the Royal Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Bernardino Molinari

Scarlatti, Two Sonatas

Bach/Busoni Ciaccona, from Partita No. 2 in D minor for violin, BWV 1004

Brahms, Twenty-eight Variations in A minor on a Theme by Niccolò Paganini, op. 35

Chopin, Preludes for Piano

Chopin, Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor for piano, Op. 31

Ravel, Jeux d'eau, for piano

Liszt, Polonaise No. 2 in E major for piano R 44

Liszt, Concerto No. 1 in E flat major for piano and orchestra R 455

His Rome début, aged 19, was at the Teatro Adriano, on the Piazza Cavour. The theatre was inaugurated on 1 June 1898 with a representation of the Amilcare Ponchielli's opera La Gioconda conducted by Edoardo Mascheroni.

(A correspondent from Moscow has written: 'The American press writes about this with a significant delay. You can read about the debut in newspapers published in Rome on December 7-8, 1939.')

His superbly elegant playing created 'the biggest musical sensation in Italy for quite some time' (The New York Times 11 February 1940). The lavish reviews clearly indicate that somehow, and mostly on his own, without guidance from a celebrated pedagogue (since age 13) Michelangeli had managed to acquire 'not only a piano technique like steel and mercury, but a musician's insight that was at once idiosyncratic but effective, dark with pessimism yet capable of warming the heart'. (John Gillespie, quoting Richard Morrison referring to this occasion)

'This is not just another child prodigy or more or less brilliant virtuoso, but the precocious blossoming of a complete artist of the first rank. In Italian music circles the new discovery is the vaunt and furor of the day. Advance reports had promised an unusual surprise, but few suspected a revelation of such magnitude.

'In Benedetti's readings, especially in the moderns, one often notes elaborately studied features of style, whose personal factors and occasional slight over-refinements offer some few debatable points. But these are small, indeed, in comparison with his consummate artistry as a whole. And they are quite forgotten in the spell of enchantment he weaves upon his listeners. Benedetti's re-creative and communicative faculties are among the most remarkable of his gifts.'

The New York Times

In Rome Arturo Benedetti gave superbly elegant performances of two Scarlatti sonatas, a Bach-Busoni Ciaccona, the Brahms Variations on a Paganini theme, several Chopin pieces and the Ravel "Jeux d'eau”. But especially in the Liszt E flat polonaise and First concerto (the latter with the Santa Cecilia Orchestra), the pianist achieved rare eloquence and aroused ovations such as are seldom heard here. In recital shortly after at the Casino Theatre of San Remo he is reported to have aroused like enthusiasm. The Rome critics chanted paeans of praise. Arturo is hailed as "the Italian Liszt" and one paper used the phrase exalting Michelangelo: "Michel più che mortal, angel divino." Certainly, his name is suggestive.

Swiss musicologist Robert-Aloys Mooser wrote in French [Geneva, July 25, 1939] to Alfredo Casella on the Siena Music Week dedicated to Vivaldi and Benedetti Michelangeli's triumph at the First International Music Competition in Geneva. (Finally, he discusseed the writing of his book on Italian musicians in 18th-century Russia.). Restricted access material (why?!) in the Fondazione Giogio Cini.

Antonio Armella p. 27:

'The three Roman newspapers devoted space to the Rome concert of December 6th (debut in the capital), reporting an audience response previously reserved only for foreign stars of the piano firmament.

On December 7th they write:

Il Messaggero

"Last night, the select Roman audience at the Adriano heard him for the first time, declaring him one of the most resounding successes ever recorded. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli is a worthy representative of Italian genius. He is a pianist of transcendental ability and an artist in the fullest sense of the word, mature and thoughtful, with extraordinary intuition. Listening to him leaves one astonished and moved; it is not only the ease of his hand or the recreational warmth that conquers. It is a superior sense of harmony, musicality, and balance that permeates the listener and exalts him (...) the audience, as we have said, tirelessly celebrated Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, forcing him to perform several unscheduled numbers."

In Il Tevere, music critic Augusto Righetti writes:

"Our pianist, not yet twenty, has a technique that we would not hesitate to call formidable: the way he overcame the diabolical difficulties of Brahms's Variations on a Theme by Paganini and Liszt's Polonaise in E flat major speaks volumes. Add to this an extraordinary variety of touch, a great richness of sound levels."

Source: Luca Rasca (Pinterest)

19 year old Arturo with Ernest Ansermet, July 1939

"Emperor"

In October 1939 in Switzerland (Geneva and Lausanne), with Ernst Ansermet, ABM performed his first "Emperor" Concerto, as reported by Antonio Armella, pp.25-26

'The interpretation of Beethoven's Fifth had enthusiastic reviews, but we already see that Benedetti Michelangeli's new piano playing attracts some murmurs, for now in a low voice, in the corridors: his Beethoven is not that of the German pianists and therefore "is not the real Beethoven".

In La Revue on October 12 signed by Paul Piguet: "His interpretation of this masterpiece not only had a transcendent authority, but also a transparency and purity that made us rediscover joys that we thought were long extinct. The sobriety of style, the rigour of rhythm, the constant moderation of the performances, the care of the contrasts conducted and measured with exemplary taste, without ever, however, alienating the most charismatic of abandonments, the superb ease of phrasing and line, testify to a truly surprising mastery in such a young virtuoso. I heard it said that his concerto is not the real Beethoven. So much the worse, and so much the better for the sunny, comforting and light Beethoven that was offered to us. It was perfectly beautiful."

After the triumph in Switzerland, he returned to play in Belgium and Italy, in Brussels at the beginning of November, in Milan on November 10, 1939, and in Rome on December 6.

The reservations about the interpretation of Beethoven's Fifth Concerto were no longer just whispered. Commenting on the Brussels concert, De Standaard, November 10, 1939, signed by M. Boereboom, reported them, amplifying them:

"The first Philharmonic concert conducted by E. Ansermet and with the collaboration of A. Benedetti Michelangeli.

In his interpretation of the Beethoven Piano Concerto in B-flat major, he shows his well-developed talent. Clarity and control are the main qualities of the young virtuoso. For many, this interpretation could sometimes appear too vague, even a little cold: however, everyone had to admire the nobility and masterful precision."

Debussy, Images

In Brussels 1938, Michelangeli played a movement of Images. His final recital in Hamburg 7 May, 1993 would include Images, which he also recorded for DG in 1971.

Images is a suite of six compositions for solo piano by Claude Debussy. They were published in two books/series, each consisting of three pieces. The first book was composed between 1901 and 1905, and the second book was composed in 1907.

Book 1 (L. 110)

"Reflets dans l'eau" (Reflections in the water) in D♭ major

"Hommage à Rameau" (Tribute to Rameau) in G♯ minor

"Mouvement" (Movement) in C major

Book 2 (L. 111)

"Cloches à travers les feuilles" (Bells through the leaves) in the key of B whole-tone (the middle section is in E major)

"Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut" (And the moon descends on the temple that was) in E minor

"Poissons d'or" (Goldfish) in F♯ major

Debussy, Images

The pianist Marguerite Long, a contemporary of Debussy, said that the composer referred to the opening motif of "Reflets dans l'eau" as “a little circle in water with a little pebble falling into it.”

"Hommage à Rameau" is a sarabande - a slow, stately 18th-century dance form - honouring the memory of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764), the great French baroque composer, especially of harpsichord music and opera. Roger Nichols has written: The central Hommage à Rameau, while outwardly placid and monumental, partakes of more traditional rhetorical structures and of the effortless internal dynamism that is so much a part of the genius of Rameau, ‘without any of that pretence towards German profundity, or to the need of emphasizing things with blows of the fist’, as Debussy put it when reviewing a performance of the first two acts of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux in 1903—which possibly inspired his piece, although searches for direct quotations from the earlier composer have so far proved fruitless.

"Cloches à travers les feuilles" was inspired by the bells in the church steeple in the village of Rahon in Jura, France.

Debussy first heard Javanese musicians at the Paris Universal Exposition and the sounds of the gamelan they played stayed with him, surfacing in the allusions to the instrument in the present piece. Writing about Java in 1913, he said, “There was once, and there still is, despite the evils of civilisation, a race of delightful people who learnt music as easily as we learn to breathe. Their academy is the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, thousands of tiny sounds which they listen to attentively without ever consulting arbitrary treatises.” The bells of the title are initiated in the first two measures by way of a whole tone scale, from which the entire piece is constructed. The simplicity of this opening belies a predominant complexity of intertwining parts that requires the music be written on three staves. A middle episode of pianistic brilliance contrasts strongly with the exotic, otherworldly sonorities of the first and last sections.

"Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut" (And the moon descends on the temple that was) was dedicated to Louis Laloy. The name of the piece, which evokes images of East Asia, was suggested by Laloy, a sinologist. The piece is evocative of Indonesian gamelan music, which famously influenced Debussy.

"Poissons d'or" was probably inspired by an image of a golden fish in Chinese lacquer artwork or embroidery, or on a Japanese print. Other sources suggest it may have been inspired by actual goldfish swimming in a bowl, though the French for goldfish is 'poisson rouge' (red fish). Or this piece, Roger Nichols has written: ‘Poissons d’or’ charts the imagined swoops and twitches of two large carp as featured on a Japanese plaque in black lacquer, touched up with mother-of-pearl and gold, that hung on the wall of Debussy’s study. Here we do indeed find him enjoying ‘the most recent discoveries in harmonic chemistry’, and taking the static ‘well motif’ from [Debussy's opera] Pelléas et Melisande and investing it with piscine acrobatics.'

Recordings (1939-43)

November-December 1939: Milan, Italy (Studio Recordings | Mono) for EMI/La Voce del Padrone (His Master's Voice)

Marescotti: Fantasque

Granados: Spanish Dance in E minor, Op.37 No.5 (Andaluza)

➢ Side 1/1 | (1939-11-?? or 1939-12-??) | 2BA 3534-? | M

– HMV DB 5354 -> Warner 0 825646 154883

– HMV DB 5354 -> EMI Italiana 7243 5 67041 2

Chopin: Mazurka in A minor, Op.68 No.2

Chopin: Waltz in A-flat major, Op.69 No.1

December 1939 – January 1940: Milan, Italy (Studio Recordings | Mono) for EMI

Grieg: Lyriske Smaastykker/Lyric Pieces in G minor, Op.47 No.5 (Melankoli), in E major, Op.68 No.5 (Bådnlåt/Cradle Song)

Chopin: Scherzo No.2 in B-flat minor, Op.31

➢ Side 1/2 | (1939-12-?? or 1940-01-??) | 2BA 3618-? | M

Side 2/2 | (1939-12-?? or 1940-01-??) | 2BA 3619-? | M

– HMV DB 5355 -> Warner 0 825646 154883 [“1941”]

– HMV DB 5355 -> EMI Italiana 7243 5 67041 2 [“1941”]

(See Christian Johansson for the documentation)

'Among other items, Spendiarow, Wiegenlied op. 3 n. 2 was recorded on 14 June 1942, and Tomeoni, Allegro on 22 January 1943 for the German company Telefunken. Alexander Spendjarov's composition (indicated in the table with the German spelling) is a new entry in Michelangeli's repertoire. His Wiegenlied/Berceuse was widely performed, although Michelangeli's recording is not supported by other evidence. Its failure to be published would not be surprising, both because he was an Armenian, well-known as a conductor and active in the Soviet Union until the year of his death (1928), and therefore by then a declared enemy of both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and because of the undisguised presence of Jewish elements in the titles of his compositions. However, the title appears in the list of Telefunken matrices preserved at the Warner headquarters in Hamburg.

'As for Tomeoni, it is undoubtedly Pellegrino Tomeoni (1721 - 1816), as indicated on the record label, not his son Florido, as hypothesised in other discographies (Biosa 2003, pp. 129-194; Rattalino 2006, pp. 117-151). The Allegro is the Post comunio in G major from the manuscript preserved in the archive of the Convent of La Verna, published some time ago with other organ pieces by the composer from Lucca. Michelangeli often visited the Sanctuary of Chiusi della Verna during the years of his advanced courses in Arezzo between 1952 and 1965, but he had already visited the place where St. Francis received the stigmata, during a period of convalescence that had strengthened his Franciscan faith. The concealment of the original title of the piece may be a reference to Michelangeli's notorious reserve on matters of religious faith.' (Alessandro Cecchi, University of Pisa)

In the Chopin: Berceuse in D flat major, Op. 57 (20 January 1943), 'Michelangeli plays the right-hand melody at the beginning slightly after the left for emotional effect and generously uses rubato to shape the phrases. In fact, this is a surprisingly free performance, more like an improvisation, in which Michelangeli slows the tempo at will. ' (Jonathan Summers, here observing a feature which the pianist would employ thought his career, one occasionally thought anachronistic for a musician who claimed to give an unvarnished account of the music)

James Methuen-Campbell has described the disc of the Berceuse as 'one of the finest interpretations of this work ever captured in recording. His use of rubato here is charming, and the whole performance is characterised by refined emotion, though hsi style is very relaxed.'

'Between the first recordings for HMV in 1939 and the Telefunken discs, Michelangeli set down his first major work, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in C major Op. 2 No. 3, for HMV in Milan in 1941. This is a wonderful performance from the twenty-one year old Michelangeli, aristocratic and sublime from the opening, a combination of controlled powerful virtuosity and playing of the most lyrical poise. His control of the dynamics is caught well by the recording engineers and in the Adagio, although he plays with a sweet and beautiful tone, the movement never becomes cloying whilst the tempo is perfectly maintained. Michelangeli’s dexterity in the final Allegro assai is remarkable and whereas many pianists give a feeling of a struggle to maintain their opening tempo when the semiquavers (sixteenth notes) appear in the fifth bar, Michelangeli sails ahead unimpeded.'

(Jonathan Summers)

The difficulty of locating verifiable recording ledgers for Michelangeli’s Milanese solo piano sessions for La Voce del Padrone (His Master’s Voice) and Telefunken has made the identification of precise recording venues and dates a confusing and uncertain undertaking. The recording dates reproduced in the accompanying documentation for this Naxos release are the result of the most recent research carried out by the Italian discographer on Michelangeli’s recordings, Angelo Scottini. The matrix numbers of the published recordings of the Berceuse and the Mazurka No. 25 suggest that these were recorded later, on 20 January 1943. The exact venues for the solo piano recordings on this recording are not known, though there is anecdotal evidence that some took place at the Conservatorio Verdi.

Enrique Granados, Andaluza

Pantaleón Enrique Joaquín Granados Campiña (27 July 1867 – 24 March 1916), commonly known as Enrique Granados

'This aesthete's [AMB] approach to piano sound, however, was not without stylistic concerns. Listen to Granados's Andaluza. Benedetti Michelangeli does not perform the piece with composure/consistency (compostezza): with control and detachment, yes, but not with stylistic consistency. (compostezza di stile).

'Andaluza's Art Nouveau sentimentality is fully embraced, and the rhythm is perpetually oscillating and panting, and the melody sighs and moans, rises and falls. Benedetti Michelangeli sounds stylistically like Granados, who left us a roll of mechanical piano from Andaluza, and we find the same style in Albeniz's Malagueña. Now, Albeniz and Granados were much leaner and more composed (assai più asciuti e più composti) than Benedetti Michelangeli by pianists much older than Benedetti Michelangeli, such as Rubinstein, Lhevinne, and Cortot, while Benedetti Michelangeli seems, if anything, closer to Granados himself or to [Moriz] Rosenthal or [Emil von] Sauer. Where did this anachronistic stylistic placement come from? It seems likely to me that it came to Benedetti Michelangeli from his teachers, Paolo Chimeri (born in 1852) and Giovanni Anfossi (1864), the latter a teacher of great value, but whose cultural position was certainly not avant-garde («Anfossi said with regard to the "Sonatina seconda" that I don't know what I'm doing, believe me»», wrote Busoni to his wife on 28 September 1913).

(Piero Rattalino, From Clementi to Pollini, 341-2)

I myself have no problem with the 'sighs and moans' and find it an exquisite performance, deeply Spanish and characteristic of the 'canto hondo' tradition.

La Verna

Michelangeli spent a year (dated by Piero Rattalino to the 1950s while ABM was teaching in Arezzo) at the Laverna / La Verna Monastery, apparently with the intention of becoming a Franciscan Brother.

It was in the earliest years of the thirteenth century that one of the most important Franciscan sanctuaries was built in the Tuscan Apennines. Standing on Mount Verna, which Saint Francis of Assisi chose as its location, the monastic complex is today the end-point of pilgrimages from every corner of the world. It all started when Francis met Count Orlando Cattani, the local feudal lord, who was persuaded to donate the mountain of La Verna to the friar.

The sanctuary's location, standing on a cliff amidst the greenery of the Casentino woods, makes it one of the most beautiful in Italy, and its close connection to Saint Francis makes it one of the most significant. Even Dante wrote admiringly of it, when in Paradiso XI (106-108) he refers to it as a crudo sasso (naked crag) and recounts the story of the final seal, the stigmata that Francis received (on 17 September, 1224).

The pianist was once asked about the temple of Scarbo. 'It's simply vivo, lively, not fast.

Of course there are thousands of nuances behind such directions. I sense it. I feel the right tempo, and after all I knew Ravel.'

'I remember how the Maestro mentioned their acquaintance once. As a young pianist, he played this difficult cycle in front of the composer, to which Ravel apparently responded: "I didn't know I'd composed such beautiful works!"'

Lidia Kozubek, p.50