Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920-1995)

1946

First tour of Great Britain. In Trento, he meets the Pedrotti Brothers, founders of the SAT Choir, for whom, in the following years, he will harmonize 19 mountain songs.

His first appearance in London in 1946 was with the London Symphony Orchestra at the Albert Hall where he played Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in E flat and César Franck’s Variations Symphoniques. (Jonathan Summers)

Sunday 8 December 1946, His Majesty's Theatre at 3pm, "Italy's Greatest Pianist", Only London Recital (presented by Harold Holt Ltd.). Programme will include Brahms-Paganini, Stravinsky Danse Russe, Bach-Busoni Chaconne and Beethoven Op.2/3 in C major. In the Evening Standard (10 December), Desmond Shawe-Taylor wrote: 'Another Horowitz. His finger control dazzling, his scale passages uncommonly even, his gradations of tone of the finest, and his part-playing about as clear as any I have ever heard. There was a freshness and an element of surprise which partly recreated the shock with which this music must have bust upon its first listeners.' The Daily Herald extolled: "Few pianists could do it".

'After the war, his engagements in Europe and overseas increased. In 1946, as a budding piano star, he presented himself in London, where he returned many times during his life. After appearances in Brussels and Zurich, he returned to a sold-out La Scala in Milan in November 1947, where he played with the Turin Symphony Orchestra and conductor Mario Rossi to perform Beethoven's Fifth Concerto. The piano part of the concert was a great success with the audience, and alongside Beethoven, Dallapiccola's two orchestral pieces were played, which literally provoked a "fight between the orchestra and the audience", who "whistled, screamed and generally made it impossible to listen to these musical innovations" during the performance.' (Corriere della Sera. 25. 11. 1942)

Katia Vendrame (Brno, 2022)

Camillo Togni was a favourite student, and later a close friend of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. He attended his classes assiduously from 1945 to 1948—when Benedetti Michelangeli lived with Camillo’s aunt, Esterina Togni in Gussago, near Brescia—then less frequently up until 1953. Togni and Benedetti Michelangeli were linked by a close bond of mutual admiration up until the composer’s death in 1993. Benedetti Michelangeli intended to include Togni’s Seconda Partita Corale (1976) which was dedicated to him, in his repertoire; he recorded Togni’s cadenza for Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K.503 (1989) and he would have performed Togni’s cadenzas for the Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K.491 in the autumn of 1993 if illness had not prevented him from doing so. (Aldo Orvieto)

In the Ricordi Archive, there is a letter dated 8 March 1946 (Mazatlán, Mexico) from Elsa Respighi Olivieri Sangiacomo (1894-1996, wife of Ottorino Respighi) to Guido Valcarenghi which includes the following:

'I'm waiting for news from [impresario Ernesto] De Quesada about the Colón and Rio de Janeiro seasons, and I'd be happy if you could write me something about them. Benedetti Michelangeli was supposed to come to South America this year, but unfortunately he seems to have withdrawn due to health reasons. I suggested Franco Mannino or Sangiorgi, but it's certainly not the same thing!'

1947

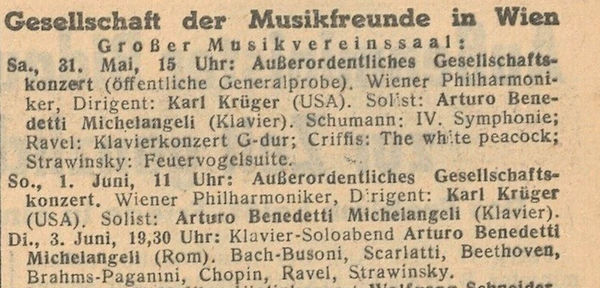

Vienna, May/June 1947. But ABM's only two listed "Klavierabend" recitals in the Großer Saal of Vienna's Musikverein were both cancelled (8 March & 3 June, 1947)

Wednesday, 11 June 1947, Teatro Argentina, Rome

Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Antonio Pedrotti

Mozart Concerto No. 20 in D minor for piano and orchestra K. 466

Schumann Concerto in A minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 54

Ravel Concerto in G major for piano and orchestra

30 July, 1947 Rome. Basilica of Maxentius

Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Antonio Pedrotti

Dvořák Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 "From the New World"

Liszt Totentanz, for piano and orchestra R 457

Grieg Concerto in A minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 16

Michelangeli made his first appearance with the Ravel Concerto at the Edinburgh Festival in summer 1947 with the Scottish [National] Orchestra under Walter Süsskind. This was the inauguration of the Festival. "In 1947, after the devastation of World War II, the founding vision for the Edinburgh International Festival was to reunite people through great art. In that first year, people overcame the post-war darkness, division and austerity in a blooming of festival spirit. Over the past eight decades, that same vision has ignited an astonishing breadth of thrilling cultural experiences across the arts. As the first Festival approached in 1947, rations were still in place and the Minister for Fuel and Power banned floodlighting the castle at the inaugural International Festival. But the people of Edinburgh felt differently. They wanted visitors to appreciate their magnificent castle, floodlit at night. Hundreds of letters and telegrams poured in with generous offers to donate coal rations. The Minister had no choice but to relent."

24 November 1947, Milan - Teatro alla Scala. Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 'Emperor'

- Mario Rossi conducting Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI (the first recording which exists of ABM in this work)

1948

He recorded the Bach-Busoni Ciaccona and the Brahms-Paganini Variations in London. He was a member of the jury at the Scheveningen (Netherlands) and Budapest piano competitions. He toured Great Britain again: at the Edinburgh Festival, he played the Bethoven Triple Concerto with Gioconda De Vito and Enrico Mainardi, accompanied by Furtwängler.

21 March 1948, Rome, Teatro Argentina

Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Antonio Pedrotti, piano: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli

Handel Water Music: Suite

Mozart Concerto No. 23 in A major for piano and orchestra K. 488

Masetti Idyll and Dithyramb, for orchestra

Franck Variations symphoniques, in F sharp minor, for piano and orchestra

15 June 1948, Grosser Konzerthaus-Saal, Vienna (?). Haydn D major concerto, + Ravel; also Mario Peragallo, La Collina. Wiener Symphoniker under Antonio Pedrotti

8 September 1948 Tour (Edinburgh) 1948 Edinburgh. Usher Hall ?

Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia

conductor: Wilhelm Furtwängler, piano: Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, violin: Gioconda De Vito, cello: Enrico Mainardi

Cherubini Anacréon: Overture

Brahms Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

Beethoven Concerto for Piano, Violin, Cello and Orchestra, Op. 56

Beethoven Leonore III, Overture in C major op. 72a

10 September 1948, Usher Hall, Edinburgh, Scotland. Orchestra dell'Accademia di Santa Cecilia under Vittorio Gui (a very great Rossini conductor). ABM played the Schumann Concerto (also Cenerentola overture and Brahms 3)

The Grand Finale in Edinburgh. Special report from the "Weltpresse" by Joe Lederer

Edinburg, September 15. The grand finale began with a roar: The Augusteo Orchestra from Rome, which first performed under the direction of the young Italian Carlo Zecchi, gave two magnificent concerts with Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting.

On the first evening, Dr. Furtwängler conducted Brahms's Second Symphony after Cherubini's "Anacreon" Overture. Beethoven's Triple Concerto for piano, violin, cello, and orchestra (Op 56), with the three Italian soloists, pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli, violinist Gioconda de Vito, and cellist Mainardi, was followed by the third Leonore Overture, this jewel that no other conductor makes sparkle as much as Furtwängler.

Die Weltpresse (15.9.48)

October 1948: Abbey Road Studios, London, England (Studio Recordings | Mono for EMI)

Brahms: Variations on a theme by Paganini, Op.35 [edited by Michelangeli]. DETAILS

Bach/Busoni: Chaconne from Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004

Debussy: Reflets dans l’eau (Images, Book I No.1)

Galuppi: Presto in B-flat major

Of the Brahms, Richard Osborne wrote in 2021: 'A yet-to-be-surpassed account of these variations of hair-raising difficulty'.

c.15 October 1948, Konzerthaus, Vienna

The first subscription concert of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra plunged into the music without the usual sonorous preface of an effective overture. Arturo Benedetti

Michelangeli sat down at the piano, Dr. Karl Böhm stepped to the conductor's podium, and

Schumann's Piano Concerto began. In the virtuoso hands of a modern piano master, for whom precision, objectivity, delicacy, and technical perfection are paramount, the Schumann concerto was transported from the romantic moonlit night into the bright day, and the blue flower of Romanticism was chemically polished (die blaue Blume

der Romantik chemisch geputzt).

Emil Sauer, as the last of the old Romantics, made this concerto rave and revel in emotion,

but the era of this poetic, broad-sounding, and exuberant Romanticism is

arguably over. The modern Romantic no longer lets his hair flutter, but wears it short and elegantly styled. In this modern Romanticism, Benedetti Michelangeli is a true master with perfect technique, polished passagework, and the finest blends of sound. His Schumann lives in a house furnished with tubular steel furniture and lit by concealed lamps, and the rapturous Romantic takes to the telephone and speaks here softly and precisely. Thus, in the playing of this interesting Italian pianist, old and new times, Romanticism and the present are present. After the Schumann Concerto, which was received with great acclaim, the virtuoso piano chemist played a piece by Scarlatti with dazzling music-box technique and a piece (Danza e Canzone) by Mompou with the finest nuances of sound and color. The second half of the concert belonged to Bruckner, whose Seventh Symphony was performed by Dr. Böhm. (Weltpresse 15.10.48)

30 October, 1948: Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

Bach-Busoni, Ciaccona; Scarlatti, Andante; Galuppi, Allegro; Beethoven, Sonata op. 111; Ravel, Valses nobles et sentimentales; Debussy, Images; Brahms, Variazioni su un tema di Paganini.

USA, 1948-48

In 1948 Michelangeli toured the United States for the first time, making his orchestral debut at Carnegie Hall in November, performing Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 54 with the New York Philharmonic and Dimitri Mitropoulos (18 and 19 November). He withdrew abruptly in the middle of this 1948-49 U.S. tour, lamenting what he perceived as his promoter’s desire for him “to act as if I were from Barnum’s circus.”

In November 1948, he left for the United States to begin his public performances: in New York's Carnegie Hall (18th), he played Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of the Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos, a pupil of Ferruccio Busoni. The same evening Mitropoulos' transcription of Bach's Fantasia and Fugue in G minor, BWV542 and Mendelssohn's Scottish Symphony.

Michelangeli's interpretation of the Schumann concerto appears unusually freer and more impulsive than is usual in the pianist's recordings from later years. This may also be a reaction to the conductor, who supports such a freer and more brilliant interpretation in the orchestral parts. It was during these years that Michelangeli reached the highest levels in terms of technical ability and therefore virtuosity, and this recording of the Schumann concerto is proof of this. Musicologist Pietro Rattalino describes this performance as an "enormous explosion, very direct", (“esplosione terribile, direttissima”) both artists really burst forth with beautiful music, probably because at that time the pianist's depression and the heavy psychological pressure he felt before his performances had not yet begun to manifest themselves.'

Katia Vendrame (Brno 2022)

Musical America (1.12.48) wrote: Arturo Michelangeli, whose appearances with the Philharmonic Symphony were his first in the United States, does not need to cite his presumed descent from Michelangelo in order to reinforce his position, for he is an important and valuable artist in his own right. Some of his interpretative ideas about the Schumann concerto were, to be sure, lively material for intermission debate. But even

though he often flouted, or perhaps did not even know, the traditions which are usually upheld in the performance of this work, his own view of it was provocative, and full of integrity, and always motivated by a musical rather than an exhibitionistic purpose.

On the purely mechanical side, his ability is altogether wonderful. His soft playing is supremely beautiful; he can diminish to the merest thread of sound without letting the tone lose its body, and his legato is unimpeachable.'

1949

1949 was the centenary of the death of Fryderyk Chopin. In Michelangeli's life, this year is characterized by concerts with Chopin's compositions in the programmes, such as his Piano Concerto No.1 in E minor Op.11, which was scheduled for 14 May and was to be played as part of the "Pomeriggi musicali" program in Milan at the "Teatro Nuovo" with conductor Carlo Zecchi. No recording exists.

The first piano concert was also part of the Chopin festival organized by the "Associazione Riunita dei Concerti" (Arc) association founded by pianist Enzo Calaco - a student of Busoni and teacher of Claudio Abbado.

Unfortunately, due to Michelangeli's indisposition, the concert was canceled at the last minute. The following day, the press commented on the pianist's act with a slight irony: "nevertheless, he will play tomorrow and Thursday in the same theater, which in a way proves that some of the artist's indispositions are serious". (Corriere della Sera. 15. 5. 1949)

Katia Vendrame (Brno 2022)

Friday 7 January 1949, Northrop Auditorium, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The 27-year-old pianist who has electrified Europe with his playing will be making his first Minneapolis appearance with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, under Dimitri Mitropoulos. He is a direct descendant of the famous Italian artist and sculptor, Michelangelo [?]. He will play César Franck's Symphonic Variations and Liszt No. 1. The orchestra will play Berlioz's Roman Carnival and Rachmaninoff's Symphonic Dances. William Schuman's sprightly 8-minute "Circus Overture" will conclude.

(Star Tribune, 2.1.49)

16 January, 1949: Los Angeles, California

Franck: Symphonic Variations for Piano & Orchestra

– Alfred Wallenstein / Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra

Carnegie Hall début, 30 January 1949

30 January 1949, solo début in Carnegie Hall, New York. Olin Downes wrote in The New York Times:

'Michelangeli, whose last name alone and itself sufficed to head his programme, and who had made a successful appearance as a pianist at a Philharmonic Symphony concert earlier in the season, gave his first New York recital last night in Carnegie Hall. He played a programme that began with two of the delightful sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti and ended with the monumental Brahms-Paganini Variations.

Mr. Michelangeli's pleasing tone and extensive technique served him well in the sparkling music of Scarlatti, although reservations on the stylistic side could be made. He was less fortunate in the Bach-Busoni chaconne, more or less slaughtered to make a virtuoso's holiday. Mr. Michelangeli could play anything there was there to play, and he did so, often more swiftly and more thunderously than was necessary, at other moments with a sentimentalizing of the melodic line, and in general with a superficiality which characterized most of his playing of the evening. To perform plausibly with an orchestra can be one thing, and to perform as a soloist with mastery and originality, another. The Beethoven C major Sonata was best in the lighter movements, and least convincing in the slow movement, where more depth is demanded. When Mr. Michelangeli had finished with the classic portion of the programme there remained the possibility that in Romantic music he had his greatest strength. But it did not appear to be so. The Chopin Berceuse was prettily played, with due finish of filagree and beauty of tone. But the B flat minor Scherzo was a performance which entirely missed the dramatic intensity as well as the formal logic of the music. It is one of Chopin's most intense and passionate expressions. It was made a parlor piece, and it may indeed be said of Mr. Michelangeli as an interpreter that he provided the parlor conception. That music means not only notes but a penetrating comprehension and imagination would not have been imagined from his performances.'

Musical America 2/1949 was more enthusiastic: 'His performances were magnificent, and he received one of the most tremendous ovations a New York audience has given to a newcomer in many years. Not only does he possess a complete command of the instrument; he is a supremely sensitive and imaginative interpreter, equally at home in Scarlatti, Chopin and Brahms. He can produce iridescent colours and orchestral sonorities, but he never violates the musical line or the intellectual significance of a work for the sake of display. Mr. Michelangeli is an aristocrat among pianists. His nobility of style is illumined by a passionate temperament which has been so disciplined that he can play with both concentration and rhapsodic intensity.

The Scarlatti Sonatas in B minor and in G major that opened the program were beautifully phrased with feathery touch and liquid tone. There is not a waste motion in Mr. Michelangeli’s playing. He has both the highly articulated finger technique of the harpsichord style and the weight touch of the modern piano at his command. This latter device came to the fore in his performance of the Bach-Busoni Chaconne, in which his frequent changes of tempo and coloration were startling, yet wholly justified by the nature of the transcription. His tone remains golden in quality even at the extremes of volume, because he never tightens a muscle, no matter how exciting or exacting a passage is.

The crown of the evening was Mr. Michelangeli’s transcendent performance of both books of Brahms’ Paganini Variations. A double barrel of complimentary adjectives would be richly deserved, but would defeat their own purpose in describing it. Each variation was consummately thought out and executed, and all were unified in a great crescendo.

The sudden changes of dynamics, the incredibly rapid and accurate passage work in contrary motion, the prismatic pedal effects, the constant play of mood, from humor to ferocious passion—these were the work of a master pianist. Let us have more of

Mr. Michelangeli.'

2 May, 1949, Teatro Argentina, Rome

Chopin Fantaisie in F minor for piano, op. 49

Chopin Prelude in C sharp minor for piano, Op. 45

Chopin Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor for piano, Op. 35

Chopin Berceuse in D flat major for piano, Op. 57

Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor for piano, Op. 31

Chopin Three Studies for Piano from Op. 10

Chopin Grande polonaise brilliant preceded by an Andante spianato, for piano op. 22

5 May 1949, Bologna

Weber, Il Franco cacciatore, [Der Freischütz] Ouverture; Petrassi, La follia di Orlando; Martin, Ballata per pianoforte e orchestra; Liszt, Concerto per pianoforte e orchestra n. 1.

Antonio Pedrotti, direttore d’orchestra.

Il Quotidiano, 18 May 1949 announced that ABM would hold a course of interpretation 23-30 June in honour/remembrance of pianist. and composer Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) in Studio Casella, Via Giovanni Nicotera, Rome.

Compositions included: Scarlattiana, for Piano and Small Orchestra, Op. 44 (1926), Notturno e Tarantella for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 54 (1934). David Hurwitz says that the 1937 Concerto for Orchestra, Op. 61 deserves standard repertoire status.

17 & 21 June 1949

The renowned Italian pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli has confirmed his participation in the Vienna Music Festival. In a concert conducted by Karl Böhm on June 17 in the Great Concert Hall, he will perform Frank Martin's Ballade with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. The same concert will feature the premiere of the Second Symphony by the young Austrian composer Karl Schiske. Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli will also give a Chopin evening on Tuesday, June 21, as part of the Konzerthaus Society's Chopin Cycle.

(Wiener Kurier, 25 April 1949)

His delicate, springy touch (in Chopin recital), his excellent use of the pedals, and the fine nuances of the sound effects extract an unusually rich range of tones from the keys and a sonorous, rich piano. His runs, trills, and fioriture sparkle like a cascade of glittering jewels, and no one asks whether some of these gems aren't Pierre de Strass. The legato playing, however, is not entirely perfect; the phrases sometimes become disorganized, and the performance is occasionally disconcerted by the occasional unfounded rubati and ritardandi. His interpretation is convincing where it can and should be objective: for example, in the finale of the B-flat minor sonata, which he chases across the keys like a hurricane with a ghostly eeriness, or in the F-minor Fantasy, which he structures coolly, clearly, and vividly. But when it comes to letting Chopin's wonderful expressive cantilenas, which are actually supposed to begin to sing from within themselves without any external, effective suggestion, flow forth, the objectivity and crystal clarity that Michelangeli is so famous for, become a disadvantage. Is it possible to play Chopin in any other way than subjectively and romantically? Is it conceivable to objectively interpret the "Berceuse" or the C-sharp minor Prelude like a fugue from the "Well-Tempered Clavier" or a didactic piece by Hindemith, without rewriting their inherent romanticism based on one's own subjective perception? Is this especially possible for a compatriot of Bellini, whose delicate, rapturous cantilenas made such a deep impression on Chopin? An interesting evening and a master pianist: but when it comes to Chopin, not our man.

Neues Österreich 29 June 1949

1949 Official pianist at the memorial ceremonies for Frédéric Chopin (first centenary of his death). Tour in Argentina. Member of the jury of the "Premio Busoni" piano competition in Bolzano, of which he is a co-founder.

Polish newspaper Gazeta Ludowa (18 June 1949) reports that the Polish Ambassador to Italy H.E. Adam Ostrowski , visited the mayor of Florence, Mario Fabiani to open an exhibition of Polish graphics organised in one of the rooms of the Palazzo Vecchio, and on the 14th he was present at the gala concert honouring Chopin in the Teatro Comunale, when the distinguished pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli performed.

In the autumn of the "Chopin Year", Michelangeli was invited to become part of the jury of the first edition of the Busoni Competition in Bolzano, where his good friend and director of the Conservatory, Cesare Nordio, lived, who had helped organize it and played a significant role in its organization. Nordio worked as a pianist and teacher at the Bolzano Conservatory for about ten years. The final of the competition took place on September 23, 1949, when nine of the twelve finalists were Italian. The first prize was not awarded; the second, offered by the jury member Michelangeli himself, was awarded to “Lodovico Lessoni from Turin; the third to Rossana Orlandina from Pisa, the fourth to Alfredo Brendel from Graz and the fifth to Bela Siková from Budapest”. The jury, alongside Artur, included Nikita Magalov, Jacques de Fevrier, Egon Kornauth and Gino Tagliapietra, Busoni’s pupil.

Corriere della Sera. 24. 9. 1949,

1949-50 Teacher at the Venice Conservatory.

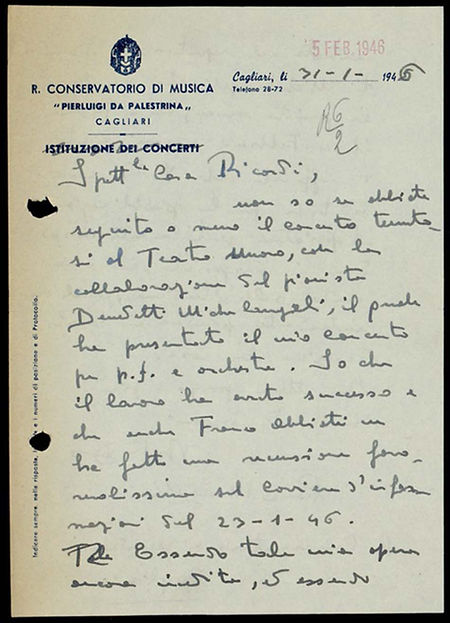

Dear Casa Ricordi,

I don't know whether or not you attended the concert held at the Teatro Nuovo, with the collaboration of pianist Benedetti Michelangeli, who presented my concerto for piano and orchestra. I know that the work was a success and that Franco Abbiati also gave it a very favorable review in the Corriere d'Informazioni [sic] of January 23, 1946.

Since this work of mine is still unpublished and has entered the repertoire of Benedetti Michelangeli, who will perform it for the fifth time in Rome on February 14th, I would be happy to offer it to your publishing house for publication. Please respond promptly should you wish to consider the matter.

In the meantime, I offer my most sincere regards.

Franco Margola

31 January, 1946; Cagliari

(Italian transcription by Federica Marsico, Archivio Storico Ricordi; English by Google)

South America

Brazilian newspaper Correio Paulistana (16 March 1949) notes that Michelangeli will perform in the Teatro Municipal, Rio de Janeiro. But see below...

21 July, 1949: Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A recording from a Radio Belgrano broadcast.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.3 in C major, Op.2 No.3

Chopin: Mazurka in A minor, Op.68 No.2, in B minor, Op.33 No.4

Chopin: Andante Spianato & Grande Polonaise Brillante, Op.22

Encores:

· Grieg: Lyric Piece in E major, Op.68 No.5 (Cradle Song)

· Galuppi: Sonata No.5 in C major

· Grieg: Lyric Piece in G minor, Op.47 No.5 (Melancholy)

Despite the poor quality of the recording, it is possible to hear the clear singing tone of the right hand in the Andante spianato e Grande Polacca brillante, which is combined with very calm playing with large breaths between individual long phrases, in contrast to the brilliant virtuoso parts, where the sound suddenly becomes very light.

Katia Vendrame

Enzo Valenti Ferro, 100 años de música en Buenos Aires : de 1890 a nuestros días has different dates. On 28 July, ABM began a series of five recitals at the Colón with 2 Scarlatti sonatas, Bach-Busoni Chaconne, Beethoven Sonata No. 3 in C, Debussy Images I and Brahms/Paganini.

19 August 1949. ABM was due to play Haydn's Concerto in D major, Hob XVIII:11, Op. 21 and Mozart's concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 for the Asociación de Amigos de la Música but he cancelled this and other engagements, as he had to undergo surgery. Diario da Noite (31 August 1949 ) announces that ABM has had to cancel his Brazil concert for Pro Arte in São Paulo on 9th September because of this emergency surgery (appendectomy); he will return to Italy.

A recital was announced for Tuesday 23 August 1949 in Teatro El Círculo, Rosario (186 miles northwest of Buenos Aires) at 9:45pm, but on the 20th Diario Crónica published: 'Pianist Michelangel will not perform for now. The third concert by Italian pianist Arturo Michelangel, who was scheduled to appear at Circulo, was announced for next Tuesday. Reasons beyond the control of the company and the concert artist have led to the postponement of the performance, to a date that will be set shortly. At the time of his presentation, the prestigious concert artist will offer a top-notch repertoire (Bach, Beethoven, Scarlatti, Debussy and Brahms).'

On 20 May 1949, Maria Meneghini Callas made her Buenos Aires debut in the Teatro Colón as Puccini’s Turandot, in performances conducted by Tullio Serafin. In addition to the four performances of Turandot and four of Norma in May and June 1949, she sang a single Aida on 2 July and appeared in a gala performance celebrating the Argentine Oath of Independence one week later. It was Callas’ only operatic season in Argentina.

An eleven-year-old Martha Argerich would play Schumann's Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54 in the Teatro Colón on 26 November 1952 with Washington Castro conducting Orquestra Sinfonica de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires.

Baldassare Galuppi (18 October 1706 – 3 January 1785) was a Venetian composer, born on the island of Burano in the Venetian Republic. He belonged to a generation of composers, including Johann Adolph Hasse, Giovanni Battista Sammartini, and C. P. E. Bach, whose works are emblematic of the prevailing galant music that developed in Europe throughout the 18th century. He achieved international success, spending periods of his career in Vienna, London and Saint Petersburg, but his main base remained Venice, where he held a succession of leading appointments. Michelangeli also had in his repertoire Galuppi: Presto in B-flat major.

La Sonata in do maggiore di Galuppi. Lì ha un timbro che non sembra un pianoforte, sembra uno strumento inventato da lui. Un suono che non esiste.

'Galuppi's Sonata in C major. It has a timbre that doesn't sound like a piano; it sounds like an instrument he invented. A sound that doesn't exist.' (Piero Rattalino)

Michelangeli's teaching activity continued in Venice, Berlin, Geneva and Budapest. His concept of training students to become professional piano concertists[definition needed] was unorthodox but successful, and he taught for several years in Bozen, and from 1952 to 1964 in Arezzo (with a break caused by ill health between 1953 and 1955). The courses eventually resulted in the foundation of the Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli International Piano Academy, which was to be organized by the city and provincial authorities in Arezzo, in cooperation with the 'Amici della Musica' Society. Unfortunately, the project did not come to fruition. He ran further courses in Moncalieri, Siena, and Lugano, and from 1967 he gave private tuitions at a Rabbi [clarification needed] in his Alpine villa in the province of Trento.

'We are in western Trentino, where the small Val di Rabbi branches off from the Val di Sole. Here, in a tiny hamlet surrounded by woods, is the Alpine hut that served as Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli's refuge for three decades. The great pianist's wife, visiting the Milan Trade Fair, came across building and pointed it out to him. He was immediately won over and decided to purchase it. He reserved the ground-floor rooms for his advanced training students, each equipped with a piano. On the first floor, he placed the common room, with its traditional stube and fireplace, while the bedrooms and his study were on the second. When the number of students increased—Americans, Slavs, and especially Japanese, a select group from whom he charged no compensation—he built another cabin next to the first, where his two Steinway grand pianos were housed in the larger room. The students stayed for extended periods, and he established a family atmosphere with them, a sense of community. He was a skilled cook, and in the evenings, he enjoyed cooking for everyone, then staying late to chat. His most intimate relationship was with Signora Gemma, the housekeeper who would care for him for three decades. A touching memory is one winter when Michelangeli, returning from a tour with two Japanese students, suggests to Gemma that they put up a Christmas tree for his children and those in the hamlet. He says he hadn't had one since he was little. And the Japanese girls take care of the decorations, making beautiful ones even just from candy and chocolate wrappers. He was an avid reader of "Topolino" (Mickey Mouse).'

(Alessandro Tamburini, Avvenire, June 12, 2025)

Alessandro Baricco on Galuppi

Michelangeli spalancava radure fra le note di Galuppi

Ss he's gone, Benedetto Michelangeli, in his own way, without warning. From what I understand, there's a one in a billion chance: but if he ends up in the same place where Debussy has been wintering for decades, you know what an encounter. Eternity won't be long enough for those two: they have a whole world of sounds to tell each other, their own stuff, the others have never understood a thing, it's a world that existed only in their ears. If they explain it to each other, just by looking into each other's eyes, you can bet, they won't even need a piano. A look and away.

It's not that I'm exactly a Benedetti Michelangeli fanatic, I couldn't say that, but by dint of reading, I was overcome by that irresistible nostalgia that until a minute before had objectively non-existent - that little bit of sadness that was enough to make me find myself "standing there looking for that record among the records, without finding it, of course, but with the precise sensation that if I hadn't found it I would have gone out and bought it, because if I didn't hear it I would have gone mad.

The record on which he played Galuppi, Galuppi's name was Baldassarre, and he was a Venetian composer, one of those who are almost forgotten now. Born and died in the eighteenth century. He wrote a lot of stuff, and among other things a lot of sonatas for stringed instruments. keyboard, and among the many, one, in C major: and it was the one Michelangeli played. Probably, if he hadn't played it, it would have disappeared into thin air long ago. But, God knows why, he had fished it out of the deck, and played it. And so no one will ever forget it. It starts like a Paradise: I remember that for sure. The beginning leaves you speechless. Reading it, it's music of an insane simplicity, there's absolutely nothing, the left hand playing a banal Alberti bass and the right stringing the notes one after the other, without doubling, just a few timid embellishments here and there, all in Andante tempo (the tempo of Paradiso, in fact). Reading it, you wouldn't give two cents for it. But you have to hear how he played it. He opened it wide. He even played it slower than it should have been, and what he did was let the light pass through. It's incredible what you can achieve if you're only capable of letting the light pass through. He did it with a piano, opening the notes, one by one, like the portholes of a schooner on the open sea. And it's also absurd, if you think about it, because the good Galuppi had never even seen a real piano, and yet with his Steinway, Benedetti Michelangeli took that artisanal detail and opened every note. I don't know how, perhaps he was fiddling with the pedal, perhaps it was just a touch. Of course, I've never heard that sound anywhere else. The fact is that in the end, it's no longer a artisanal detail, it's a clearing, a clearing, like a clearing carved out in the middle of the forest of the world. A salvation. There's something magical about it, I tried to believe, because I've been listening to it for years and searching for the right word to name the nuance of feeling that music conveys, and I've never succeeded. I challenge anyone to do so. I could be wrong, but in my opinion, that word doesn't exist: you can't even tell if it's more on the side of joy or pain. It's a strange thing, something you know but don't know. I mean, nostalgia has something to do with it, but it's not nostalgia. Wonder has something to do with it, but it's not wonder. The only thing you know is that it enchants you, yes, but you don't have a name for that feeling. And this is truly brilliant: playing something for which we haven't yet invented a name. Benedetti Michelangeli did many, but I'll remember him for that acrobatic feat there: in the absolute simplicity of a few elementary notes, saying a name that doesn't exist. Alessandro Baricco

La Stampa 14 June 1995

Sergiu Celibidache (1912-1996)

11 July, 1912, Sergiu Celebidachi [note the spelling] was born in Roman, Romania , as one of five siblings. His father, Demostene, an influential cavalry officer, was very musical, and his mother also played music. Six months after his birth, the family moved to Iași —one of Romania's most culturally important cities, with a significant Jewish population and cultural scene. Celibidache therefore learned Yiddish at an early age.

After separating from his family, at age 18 he continued his studies in mathematics, philosophy, and music, which he had begun in Iași, in Bucharest. There, he earned his living primarily as an accompanist at a dance school.

1935-37

After surviving his unpopular military service in Romania, he (presumably) moved to Paris in 1935 to continue his studies. Heinz Tiessen, a professor at the Berlin Academy of Music, recognised Celibidache's extraordinary musical potential and called him to Berlin.

1938

Celibidache followed Tiessen's call and moved to Berlin, where he enrolled at the Berlin Academy of Music.

1942-44

At the end of his studies, Celibidache wrote a doctoral thesis on "Form-creating elements in the compositional technique of Josquin des Prés, the 15th century a Franco-Flemish composer; however, as far as is known, the doctorate was never formally awarded.

1945

And now the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra entered the picture: Wilhelm Furtwängler, the orchestra's previous chief conductor, was banned from conducting after the end of the war until the conclusion of his denazification proceedings. The orchestra, in particular, was won over by the ambitious work of the highly talented young Romanian, appointing Celibidache as its new artistic director in October 1945 (and this collaboration would ultimately result in a total of 414 concerts in Berlin and on tour until 1954).

Tiessen pointed out to Celibidache the problematic musical development of his performances ("you didn't understand anything"). This, as Celibidache later repeatedly emphasized, was the decisive turning point in his development as a conductor. He then initially turned to smaller musical forms, for example by Telemann, as recommended by Tiessen, before venturing back to large symphonic works, including, for the first time in his career, a work by Anton Bruckner, the 7th Symphony.

1949

Celibidache is now a sought-after guest conductor throughout the world, conducting orchestras in Austria, Italy, France, and Central and South America, among others. This year, he is (presumably) offered the direction of the New York Philharmonic, but Celibidache declines for artistic reasons.

1950

Celibidache has undertaken further extensive and successful guest conducting engagements in Central and South America.

1954

After the death of Wilhelm Furtwängler on November 30, the orchestra chose Herbert von Karajan, not Celibidache, as its new chief conductor. And although the disputes between Celibidache and the orchestra had become quite substantial just before this decision, Celibidache did not overcome this humiliation for a long time. It wasn't until 38 years later, in 1992 , that reconciliation and two more appearances at the helm of this orchestra would come.

1958

In 1958, his first concerts took place with the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra , an orchestra with which he remained particularly closely associated for a long time, until 1983.

1963

He eventually became Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (Stockholm)'s permanent guest conductor and artistic director in 1963. In addition to concerts in Stockholm, the orchestra also performed concert tours in Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Finland, Austria, the Netherlands, and Romania.

1966

In 1966, he returned to the helm of a Berlin orchestra, this time with the Staatskapelle in East Berlin, with whom he also performed in Dresden and Leipzig that year. That same year also saw his first collaboration with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, performing Mozart's Piano Concerto in D minor, K. 466, in Bologna with the orchestra of the Municipal Theatre (but what about 1942, Ravel?).

1979

On 14 February, 1979, the first concert with the Munich Philharmonic took place (after no fewer than 22 (!!) rehearsals. The programme included the Overture to Mozart's Magic Flute, Death and Transfiguration by Richard Strauss, and the Concerto for Orchestra by Béla Bartók. The concert was a huge success, acclaimed by the audience and the press, and after both sides expressed their desire to continue the collaboration, Celibidache was finally appointed Chief Conductor of the orchestra and General Music Director of the City of Munich in June. This was to be the beginning of a collaboration lasting 17 years.

1987

His first appearance at the International Bruckner Festival in Linz, performing Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 8 in St. Florian's Abbey Church.

1990

Shortly after the end of the Ceausescu regime in Romania in 1990, Celibidache embarked on a concert tour of his homeland, which was combined with an extensive aid campaign by the orchestra.

1996

On June 1, 3 and 4, 1996, Celibidache's last concerts took place. The Munich Philharmonic's program included Schubert's "Rosamunde" Overture, the Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor (with Celibidache's compatriot Dan Grigore), and Ludwig van Beethoven's 2nd Symphony. He then gave a final conducting course at the Schola Cantorum in Paris.

On August 14, Sergiu Celibidache died at the age of 84 in his hometown of Neuville-sur-Essonne, about 90 km south of Paris. He was buried there in the small village cemetery on August 16.