Still hanging on in there...

"It is still cause for wonder that Bolet tenaciously clung to the periphery of the concert world, alternately waiting for his moment or threatening to give up and make his hobby, photography, his profession. The better portion of forty years lay ahead [from mid 1930s], a seemingly never-ending crucible in which Bolet through some mysterious alchemy evolved his inimitably pellucid sound, his unique 'touch' that grew both larger and more intimate, and in the opinion of Bolet connoisseurs, more beautiful."

Francis Crociata

Hunter College

3 October 1970

'There was no question among the audience that a major new star had appeared, unexpected and unheralded.'

Hunter College 1970

David Saperton, Bolet’s teacher between 1927 and 1934 died on 5 July, 1970 in Baltimore, at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. His address was given as 344 W72nd Street, New York City.

In 1970 [month unknown]: Casino del Aliança del Poble Nou, Barcelona, Spain - studio recording for the Ensayo label. Liszt: 12 Études d’exécution transcendante, S.139.

There seems to be a gap in the record of concerts in Britain during the period of roughly 1967-74, though further newspaper archival research may change this. But across the Atlantic, Bolet was finally making real progress. In 1970 he gave a recital at Hunter College, New York City on 3 October, in which he played - among other things - Liszt's Rigoletto paraphrase. The concert was recorded by the International Piano Library, a gala benefit for the Library which had been vandalised.

‘What a perihelion of pianists to perform!’

The New York Times, 27 Sept.1970 gave this report: On Saturday evening at Hunter College, the International Piano Library is sponsoring a benefit for itself with 10 pianists. Several months ago it was robbed; thieves broke in. ‘What they did not find was money. The IPL has always subsisted on a diet of dandelions and blue-eyed scallops. The baffled thieves instead found $200,000 of rare piano records or rolls. In fury they set fire to the IPL.’ Fortunately many discs survived including the only know copy of Grieg playing his Humoresque (worth $1,000) from acoustic recordings made for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company in Paris in 1903.

(There were precedents for this type of benefit concert, as Harold Schonberg pointed out. Fifteen pianists played in a benefit for an ill and indigent Moriz Moszkowski, a nineteenth century salon composer.)

The head of the archive Gregor Benko found that many pianists were sympathetic but, like Chilean maestro Claudio Arrau and others, were playing thousands of miles ways on 3 October. ‘He also found that some pianists, especially those concentrating on virtuoso romantic literature, regard each other, if not exactly the way Golda Meir regards Gamal Abdul Nasser, then something the way Elizabeth I viewed Philip of Spain or Arturo Toscanini regarded Serge Koussevitzky. And vice versa. Fernando Valenti, Jesús María Sanromá, Earl Wild, Bruce Hungerford, Ivan Davis, Alicia de Larrocha (president), Jorge Bolet and the great Brazilian first lady of the piano Guiomar Novaes did play.

Francis Crociata takes up the story:

'And, as an afterthought, Bolet [was invited], for Benko had never heard him play and barely heard of him. Jorge recognized the concert as the chance of his lifetime to be heard in the right context and he made the most of it. (...) The final two decades of Bolet’s life, leaving aside illness and a few bumps in the road pertaining to commercial recording, would be good years. From then to the end Jorge had all he ever really wanted.'

4 Steinways and 4 Baldwins. The Library 'was not out to make enemies'. Guiomar Novaes the grande dame of the keyboard, coaxed delicate tones from the Gottschalk's Variations on the Brazilian anthem. 'Dare one say who made the best impression? Okay pin me to the wall, and I will nominate Mr Bolet for his absolutely transcendent performances of a pair of Liszt operatic paraphrases (on Donizetti's Lucia di Lamermoor & Verdi's Rigoletto). (Harold Schonberg

When did Bolet emerge from obscurity?

Francis Crociata wrote a letter in June 1990 to the Gramophone magazine. ‘Bryce Morrison dates Jorge Bolet's emergence from relative obscurity to the "genuine and inclusive triumph" of his October 24th, 1974 Carnegie Hall recital. Many who have followed Bolet's career would date the beginning of his widespread recognition to another extraordinary occasion four years earlier... It was one of those rare and legendary occasions, like [soprano Montserrat] Caballé's New York debut, when there was no question among the audience that a major new star had appeared, unexpected and unheralded.'

In early October, in London the IPL had another benefit concert, a four hour marathon: Alicia de Larrocha, JB, Ivan Davis, Fernando Valenti, Jesus Maria Sanromá, Michael May, Raymond Lewenthal, Earl Wild, Bruce Hungerford, Guiomar Novaes, Rosalyn Tureck and Gunnar Johansen. 'What better way to call attention to the sinking fortunes [of the IPL, after the vandals' fire] than a concert on a truly Götterdämmerung scale!' Four hours of spectacular salon music proved rather too much of a good thing in spite of a much spectacularly fine fingerwork. Only Mr. Hungerford was clever enough to realize the need for a contrast: he chose a group of Schubert Ländler and played them with restraint and deliciously lilting lyricism. Miss De Larrocha (president of the IPL) offered an unusual group: a march by Albeniz composed at the age of eight, as well as trifles by Frank Marshall, Granados, Juan Torra (Miss De Larrocha's husband), and "Mrs. Juan Torra". Bach's Two-part Invention in C was spelled out upside down in the programme; no printer's error, this - Rosalyn Tureck played the piece in perfect retrograde inversion. Nor were all the surprises limited to the keyboard. At one point Beverly Sills marched on stage and announced that since Jorge Bolet had stolen her material (he had played Liszt's Lucia paraphrase) she was tempted to sing the Minute Waltz. What actually transpired, however, was a wild coloratura pot-pourri lifted from a dozen of Miss Sills's operatic roles, arranged by her accompanist Roland Gagnon ("who has been embellishing me for 10 years", the soprano commented). Carl Reinecke's Children Symphony brought the concert to a rowdy conclusion.'

The Times 12 October 1970

Gramophone advert (1978)

1971 Giovanni Sgambati, Giovanni who...?

Bolet marked the concerto in his date book for Wednesday,

1 December 1971, a performance with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914) was one of the few 19th century Italian composers to concentrate on concert rather than operatic music.

Gregor Benko says that Bolet learned Sgambati’s Concerto in G minor (1878-80) at the behest of Dr. Frank Cooper, who was then associated with Butler University in Indianapolis, Indiana. Frank Cooper sponsored a festival of Romantic music there for ten years. ‘Cooper had owned the score of the Sgambati and loved the piece, and he convinced Jorge to learn it (a somewhat difficult task, as Bolet was not anxious to learn new works). It is one of the best of the little-known Romantic piano concertos and made a "hit" every time Bolet played it, in the US and Holland. His initial performance of it was at the Romantic Festival at Butler University on May 19, 1971, with the Louisville Symphony Orchestra conducted by Jorge Mester. I was there and it was a great success indeed in every way.’

'Sgambati's 'massive three-movement Piano Concerto in G minor from 1880 might be described as a hybrid that fuses the similarly scaled Brahms D minor concerto with piano writing marked by Lisztian bravura. Imagine Liszt reworking the echt-Hungarian finale of Brahms’ Violin Concerto for piano on his own stylistic terms, and you’ll get an idea of what Sgambati’s third movement sounds like. Similarly, the grandiose first movement owes much of its existence to the arpeggiated flourishes in Beethoven’s Emperor concerto first movement and motives from Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasy.' (Jed Distler)

Mattheus Smits recalls Bolet & Sgambati

'After finishing my professional music education in Holland, I decided to continue my piano studies with a private teacher. Thanks to his son Erik, I came in touch with Johan Ligtelijn who taught privately in Amsterdam in his house next to the Concertgebouw. After finishing his piano studies in Amsterdam, Johan Ligtelijn had studied with Walter Gieseking in Hanover and later in Wiesbaden. Johan had also studied privately with Frederic Lamond, a Scottish student of Liszt, who lived in Holland during the time that he was a teacher in the conservatory in The Hague.

In the spring of 1974, I travelled to Arnhem to hear a pianist whom I had never heard of: Jorge Bolet.

After the concert I was completely flabbergasted. At my first lesson with Johan Ligtelijn after this concert, I told him that I had gone to hear Jorge Bolet and that he had blown me away. To my big surprise, Johan Ligtelijn told me that he knew him well. He had been in the audience when Jorge made his début in Amsterdam [May, 1935] and had been most impressed.

Johan Ligtelijn told me that his brother Henri Ligtelijn emigrated to the USA in 1950 and became Jorge's neighbour in Palo Alto. As Henri Ligtelijn had a travel agency, he organised all the tours for Jorge. As Jorge played in Holland frequently in the 1960s, these concerts were always Ligtelijn family reunions.

Johan Ligtelijn told me I should meet Jorge with his introduction in the autumn of 1974 when he was having his recital in the main hall of the Concertgebouw, his first after an absence of 15 years.

So the day before that concert I went to the Park Hotel in Amsterdam [*now Park Centraal, Stadhouderskade 25, near the Museumplein and Leidseplein] and saw Jorge sitting in the lounge with a man who turned out to be Tex [Compton], and another gentleman who turned out to be [the impresario with the de Koos agency] Sylvio Samama. When I told Jorge that I happened to be a student of Johan Ligtelijn, he jumped out of his chair and gave me a big hug. He immediately asked me to sit down, ordered coffee and anything else for me and started talking. We had a nice conversation and Jorge was completely surprised that a 20 year old owned an original score of the Sgambati concerto (Jorge was having to use xerox copies) and that this 20 year old could tell him exactly were he had made cuts and changes in Arnhem some month before.

This meeting, without doubt, sealed our friendship till the moment he left all of us behind.

Mattheus Smits is a Dutch music educator/piano specialist and chairman of The International Ervin Nyiregyházi Foundation. He has provided this website with many valuable personal memories.

Liszt's Dance of Death

31 January, 1971: Fair Lawn High School, Fair Lawn, New Jersey, USA

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.31 in A-flat major, Op.110

Liszt: 12 Études d’exécution transcendante, S.139: 7. Eroica, 5. Feux Follets, 9. Ricordanza, 8. Wilde Jagd

Chopin: 24 Preludes, Op.28

Encores: Schumann/Liszt: Widmung, Op.25 No.1 (S.566), Chopin: Waltz in D-flat major, Op.64 No.1 (Minute Waltz)

The Miami Herald 17 October 1971 records that Jorge (who will give a recital on Saturday evening) has been missing from the local scene for a decade; last heard here in the small Binder-Baldwin concert hall in 1963.

On 21 September 1971 Jorge performed Liszt's Totentanz with the New York Philharmonic under Pierre Boulez in the Gala opening night (a concert which included Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps). Bolet had last performed with the NYPO in 1965.

Liszt's "Dance of Death" is based on the Gregorian plainchant melody Dies irae, and completed by 1859. In the young Liszt are already observed manifestations of his obsession with death, with religion, and with heaven and hell. He frequented Parisian hospitals, gambling casinos and asylums in the early 1830s, and he even went down into prison dungeons in order to see those condemned to die. One direct source of inspiration for the young Liszt was the famous fresco "Triumph of Death" by Francesco Traini (at Liszt's time attributed to Andrea Orcagna and today also to Buonamico Buffalmacco) in the Campo Santo, Pisa. Liszt had eloped to Italy with his mistress, the Countess d’Agoult, and in 1838 he visited Pisa.

According to fellow pianist Abbey Simon (in his memoir Inner Voices), Andre Watts was indisposed and Jorge took over the performance, though he had never learned the work. He had about a week to learn it. 'You've never seen such a huge hulk of a man so nervous in your life. At the concert he started out and never stopped – he even played through all the tutti sections. It was as if he was saying, "If I stop, I won't be able to start again!" It was probably the poorest concert he ever played in New York but he never had such a success! His whole life changed. (...) There was something that was sort of lacking in his playing, this hysteria.' A student recalls the event...

Stokowski, Prokofiev: October 1971

Prokofiev 2 on 12 & 17 October 1971: Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center, New York City

"Leopold Stokowski has always put his personal stamp on the music he makes. It is part of the fascination he holds for listeners, and since he has a kind of genius he makes his idiosyncrasies enjoyable even when they seem wrong. He has never changed.

Tuesday night, at the age of 89, he led the American Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Brahms' Fourth Symphony that was a case in point. The program, which began with the Prelude to Act III of Rimsky‐Korsakov's “Ivan the Terrible,” also offered Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 2, with Jorge Bolet as soloist. This is a big, coruscating, youthful piece of enormous technical difficulty for the pianist. It also might be said to be heartless. Its success depends on the soloist's virtuosity, and this Mr. Bolet had plenty of and to spare. He plowed brilliantly and with apparent ease through the maze of notes, giving the concerto coherence and shape. This was a spectacular performance, deserving the cheers it received.

Mr. Stokowski had his ovation, too, at the end of the program. As an encore, he played Virgil Thomson's Tango-Lullaby in honor of the composer's forthcoming 75th birthday. Mr. Thomson was present to take bows. And since the audience seemed loath to let Mr. Stokowski go, he played the work again."

(The New York Times 14.10.1971)

NB Rimsky Korsakov: The Maid of Pskov (1872) listed by Stokowski as "Ivan the Terrible" (the title which had later been used by Diaghilev). It was (of course!) a Stokowski transcription.

Oliver Daniel in his biography of Stokowski has this as taking place in Carnegie Hall (p.866). Bolet mentions that the conductor has a lapse during the first of the two concerts. 'The last movement of the concerto has a middle section which is briefly introduced by the orchestra and then the piano takes it alone; it's a rather extended section - rather lyric, poet, and it must be forty-five or fifty bars of music where the piano plays completely alone, and the without interruption or break the orchestra comes in with a bassoon solo using the same theme as the piano had announced before. Well, I got to that spot and there was no bassoon. What does one do in a case like that?... So I played about two or three bars and went back to make the connection again to see if the bassoon would come in. Stokowski was completely on the moon. I don't know whether he was so entranced by the beauty of the music or what. I presume he forgot where he was or that he was conducting. It was a terrible moment. I never exactly found out how he reacted, whether it was some member of the orchestra that made some motion to him but he finally came to. Everything else went like clockwork.' (Conversation with JB, 14 December 1976)

On the above link, you can hear the slight lapse at 23:10 onwards. If this is indeed the moment, then Jorge seems actually to pause, waiting, rather than repeat a few bars.

"The Ruins of Athens" Beethoven/Liszt

11, 12, 15 November 1971 Michael TilsonThomas/ Philharmonic Hall / Manhattan, New York, in a programme which included:

Liszt / Fantasy on Motifs from Beethoven's Ruins of Athens, for Piano and Orchestra

Chopin / Andante spianato and Grand Polonaise Brilliante for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 22

Borodin / Symphony No. 2 in B minor

Pre-concert recital on Monday 15th (some of which is available on Marston CDs but dated to 11th)

Schubert / Winterreise, D.911 "Der Lindenbaum"

Schubert / "Wohin?" No. 2 from Die schöne Mullerin, D.795

Schubert / "Das Wandern" from Die schöne Mullerin, D.795 (Op. 25) (Liszt, Franz)

Wagner / "The Spinning Song" from Der Fliegende Holländer, WWV 63, arranged for piano (Liszt, Franz)

Liszt / Grand galop chromatique

Encore: Schumann/Liszt: Widmung, Op.25 No.1 (S.566)

In The New York Times, Harold Schonberg enthused: 'Most Philharmonic programs this season contain music by Liszt, and this one was no exception. But such Liszt! It was the Fantasy on Beethoven's “Ruins of Athens,” for piano and orchestra. A thorough search of the literature would fail to turn up so equally dated a period piece, one so outrageously out of fashion. What it does have is virtuosity galore and, if approached with due regard for its musical naiveté, it be a lot of fun. Jorge Bolet played it the only way it can be played. Mr. Bolet is one of the few with feeling for the romantic spirit. He did not play down the piece, though most pianists would find it hard not to. Instead he brought to it a golden tone, the suavest of legato playing and an aristocratic line throughout. On his magnificent technique one need not dwell. Only at the very beginning, at his entrance, did he sound a little flurried. The rest was flawless.'

[I actually thought his entrance sounded spectacular, but I also wonder why Bolet bothered to learn this empty piece at all! (ed.)]

In March 1984 in Walthamstow Assembly Hall (England), Bolet, Iván Fischer and the LSO recorded, among other Liszt works, this Fantasia on a Theme from Beethoven’s “Ruinen von Athen” S122, but it went unpublished: perhaps it was not completed within the time available. He had also played it during the summers of 1964 and 1966 with Erich Leinsdorf and Boston SO at Tanglewood, Lenox, MA,

The Ruins of Athens ("Die Ruinen von Athen"), Op. 113, is a set of incidental music pieces written in 1811 by Ludwig van Beethoven. The music was written to accompany the play of the same name by August von Kotzebue, for the dedication of the new Deutsches Theater Pest in Pest, Hungary. Perhaps the best-known music from The Ruins of Athens is the Turkish March. The goddess Athena, awakening from a thousand year sleep (No. 2), overhears a Greek couple lamenting foreign occupation (Duet, No. 3). She is deeply distressed at the ruined state of her city, a part of the Ottoman Empire (Nos. 4 & 5). Led by the herald Hermes, Athena joins Emperor Franz II at the opening of the theatre in Pest, where they assist at a triumph of the muses Thalia and Melpomene. Between their two busts, Zeus erects another of Franz, and Athena crowns it. The Festspiel ends with a chorus pledging renewed ancient Hungarian loyalty.

On 18 April 1972, Leopold Stokowski celebrated his 90th birthday (he was actually 93 or 94 but had mischievously shaved a few years off his age). At a party at the Plaza Hotel, New York City, among musical items, Jorge played a Balade of Chopin and William Masselos played parts of Schumann's Davidsbündlertänze; a section of the Walt Disney film Fantasia was also shown. Mayor John V. Lindsay presented the conductor with a piece of crystal.

1972 and a contract with RCA

Bolet was still teaching at Indiana, and his submission to Grove's Dictionary of Music this year is from his address at 2611 East 2nd Street, Bloomington Indiana, 47401.

His career is making real progress now as he signs a contract with RCA, but the matter is complicated. ‘RCA Records has signed pianist Jorge Bolet to a long-term contract. The announcement was made by R. Peter Munves who said: “Bolet is recognised by the musical world as one of the foremost pianists of our time.” Bolet will make his first recordings for RCA Red Seal in August in RCA’s Studio A in New York [1133, Avenue of the Americas].’

Billboard, July 1, 1972

The first recording was of Liszt's music in August 1972 (21-24th), and Jorge was at the peak of his powers. It notably included Liszt's Rhapsodie espagnole, S.254, otherwise unavailable commercially by JB. (For the ending, he always crafted on a bravura octave passage from Busoni's arrangement for piano and orchestra.). The disc, however, was only issued in 2001 (along with the Tannhäuser overture of 16 July 1973 - see below).

This RCA/Bolet actually project fell through. Francis Crociata explains – ‘The reason the master-tape [which was finally issued on CD in 2001 by RCA as Bolet Rediscovered ] languished on the shelf for thirty years was simple: R. Peter Munves left as head of the classical division at RCA. His successor [Thomas Z. Shepard] scrapped extensive planned future recording projects of two notable artists then on the RCA roster, Earl Wild and Jorge Bolet.

'On the schedule for Bolet were six solo discs devoted to Rachmaninoff, Brahms, Chopin, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Liszt and a seventh for which repertory had not yet been decided...and the heart of Jorge's concerto repertory was to be recorded with [Mexican conductor Eduardo] Mata and the Dallas Symphony. Much of that project was reassigned to the then new-star on RCA's horizon, Tedd Joselson.'

'The most important and unfortunate aspect of Bolet’s RCA experience was its abrupt end, suddenly quashed when he was at the height of his powers and playing as wonderfully as he ever could.'

A Gramophone review in August 2001, when the master-tapes were finally issued, proclaimed: 'Certainly the fire beneath Bolet’s solid, workmanlike exterior has rarely burnt more brightly than on RCA’s lavishly presented discovery.'

Jorge's father's brother Domingo Hilario Bolet Valdés (born 1881) died on 22 October 1972 in Orangeburg, South Carolina, USA.

7 October, 1972: a recital at Washington Irving High School, New York City. [The School building was located at 40 Irving Place between East 16th & 17th Streets in the Gramercy Park neighbourhood of Manhattan, near Union Square. It is named after Washington Irving (1783-1859), author of short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820), as well as several histories of 15th-century Spain that deal with subjects such as the Alhambra, Christopher Columbus, and the Moors. Irving served as the American ambassador to Spain in the 1840s.]. Jorge also performed there on 19 December 1970 (a recording exists)

Haydn: Andante & Variations in F minor, Hob.XVII:6 (Un Piccolo Divertimento), Sonata No.62 in E-flat major, Hob.XVI:52; Beethoven: Sonata No.23 in F minor, Op.57 (Appassionata); Liszt: Funérailles, S.173 No.7 (from Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses); Rhapsodie Espagnole, S.254. Below is (I believe) an encore from this recital.

Christian Johansson has written: 'The last several minutes here… wow. In Liszt he is one of the preciously few who understands the importance of declamation in the music, and has the skill to play him with the eloquence of a senator (if not the gravitas). In addition there’s his natural sense for the particular beauty of Liszt’s deeply coloured music, and the sustained imagination he requires to make the narration, not the piano writing come in to focus. A performance of Liszt like this is as rare as good Mozart playing.'

9 November 1972, solo recital: Munich, Germany

Wednesday, 29 November 1972: Jorge replaces at 24 hours' notice an indisposed Alexander Slobodyanik at the Schubert Club, O'Shaughnessy Auditorium, Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Soviet pianist's mother had died and he flew back to USSR/Russia. Jorge's Liszt selection ended with the Spanish Rhapsody, 'which may be the composer at his most meretricious...but it made a splashing closing, the audience exploding into applause' (writes Michael Anthony who - it turns out - will review Bolet against in November 1985 when he substituted for Pollini and recall this event). 'The wispy pianistic color of Gnomenreigen was taken at a whirlwind pace, yet it was accurately and thoughtfully rendered.' Peter Altman was less enthusiastic: 'Bolet delivers concert with flash, little else. On the whole, the concert was uninspiring. The playing of Beethoven's Appassionata was distressingly bad. There were an astonishing number of wrong notes. The middle Andante was thick and heavy, without lyricism. His performance never gave the work sustained momentum. His account of the Haydn Variations was attractive if strangely Schubertian.'

There is an amusing exchange of views in HiFi Stereo Review, November 1972 over Bolet's "Liszt's Greatest Hits of the 1850s" disc. Albert McGrigor takes issue with Igor Kipnis' unflattering review. Kipnis had praised Paderewski, but McGrigor replies: 'Paderewski recorded Spinning Chorus twice (VIC 6538, acoustic; VIC 1549, electrical, the worse of the two). Rhythmic accuracy is essential to the success of thie iece; it is built upon repeated left-hand figurations that must be played effortlessly and accurately. In Paderewski's hands, the purring of the spinning wheels becomes the clangor of the Fruit of the Loom machinery. There is no rhythm, thrust, shape, beauty, or style - only noise, and a desperate effort to keep the music going, somehow, some way. It is in Mr Bolet's performance that one can find "sprightliness,", "humour" and "lovely filigree". How Mr Kipnis can perceive the quality of humour in Paderewski's grimly determined performance eludes me.'

Liszt: Spinning Chorus from Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman, S.440 recorded by Bolet in 1969 in the Casino del Aliança del Poble Nou, Barcelona, Spain; issued first on Ensayo, and then in 1971 on RCA Red Seal.

Kipnis (1930-2002, himself a famous harpsichordist and prolific recording artist) replies: 'I continue to find Paderewski's Spinning Chorus full of charm, whereas Bolet's seems to me just too literal. (...) So far as representing "Golden Age" quality is concerned, Bolet's playing leaves me with a feeling of incompleteness.'

A whole page of the July edition had been devoted to the disc and the "Romantic Revival". 'I can't get too enthusiastic about some of today's neo-Romantics: the equipment is there but there is too great a generation gap. Few among the pianists of today manage to bridge it; far too many of them stumble and miss the beat - 20th century men merely reading the music through cracked 19th-century glasses.'

Bolet (recorded in Spain) 'is not a speed-demon: tempos are graceful and leisurely, perhaps at times even too much so, for I often itched for a little more daredevilry, less temperateness and complacency. Paderewski set me laughing out loud with appreciation.'

Texas' El Paso Times commented succinctly: 'RCA appears to be feeling very youthful, very commercial, for an album of some weeks ago is billed as "Franz Liszt's Greatest Hits of the 1850s." "Blazing, Brilliant, Dazzling, Demonic, Incredible, Incomparable, Unbelievable, Inimitable, Phenomenal." Played by Jorge Bolet are pieces from "Lucia di Lammermoor," "The Flying Dutchman" and such. Bolet is a very accomplished pianist and this is rather fun.'

'Where have you been...

Where were you?'

One of the most important articles on Jorge Bolet appeared in 1973, written by John Gruen for The New York Times, Sunday, 28 January, 1973. It contains a marvellous character study. ‘To sit in a desperately cheerful New York hotel room with Jorge Bolet is to know the meaning of absolute contradiction. The Cuban-born pianist is simply too imposing and disquieting a figure to meld easily with screaming red-and-orange curtains, and wildly patterned bedspreads...’ He demands a far more austere setting, possibly a sombre Buñuel set with dark, musty wall-hangings, shadows, chandeliers, sinister rugs... In a way he recalls characters out of Poe and Hawthorne.

But he says that ‘I am a very even-tempered person. I have my mother’s temperament and character. My mother was completely even‐tempered—an unruffled woman. Her sufferings, her frustrations, her sorrow were always held in. I am very much like her.’

'Bolet Recital Takes Festival by Storm'

Sunday/Monday, 21/22 January 1973 Auditorium della Conciliazione, Rome. Beethoven's fourth concerto with Guido Ajmone-Marsan and the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, in a concert which also included Bartok's Dance Suite. The conductor was an Italian-American, born in Turin, and attending the Eastman School of Music, Rochester, from where he graduated in 1968. Sir Georg Solti took a keen interest in the development of his career.

Sunday, 28 January 1973 (afternoon), Hunter College, New York City.

Four Scherzos (Chopin), Three “Petrarch” Sonnets (Liszt), “Tannhäuser” Overture (Wagner‐Liszt) Listen here

'Jorge Bolet is the current idol of the Romantic revival, and at the end of his Hunter College piano recital yesterday afternoon it was like old times at Carnegie Hall. The audience rushed to the apron of the stage as it used to do at Carnegie in the old days before the police put a stop to that. Everybody gathered close to be near The Presence, and Mr. Bolet obliged with three encores, one of which was the Verdi‐Liszt “Rigoletto” paraphrase. Not bad for a pianist who had just finished the Wagner‐Liszt “Tannhäuser” Overture. (The other two encores were the Schumann‐Liszt “Widmung” and the Schubert‐Liszt “Auf dem Wasser zu singen.”)

Primarily he seems to be interested in tone, and he has worked on tonal control as much as he has on technical exercises. Here is one pianist who has been studying the secret of the pedals. Mr. Bolet puts his educated hands on the keyboard, and a remarkable sound ensues in any end of the dynamic spectrum.

He has complete finger independence, and that enables him to bring out any kind of chordal voicing he desires. He tries for the long, singing, legato line out of the Hofmann and Rachmaninoff tradition, a line supported by smoothly pedaled basses and a keen response to harmonic change.

Thus his playing, with all its technical splendor, is varied and multi-colored. As a Romantic pianist, Mr. Bolet favors considerable fluctuation in tempo. He has learned to handle it without breaking the line; the fluctuations consist mostly of ritards for expressive purposes. But his playing has a Classical quality, in that he never—never! —goes in for the exaggerated rubato that so many consider “Romantic.” Once in a while lie underplays. It may be that, like many transcendent technicians, he has an instinctive horror of being labeled a showoff.

Be that as it may, Mr. Bolet held the fiery side of Chopin and Liszt in check. He played the four Scherzos of Chopin, and the first, in B minor, was almost contemplative. As he went along, more spirit entered his playing, and the E major Scherzo was as beautifully performed as anybody is going to hear it.

Mr. Bolet does have a tendency to dawdle a bit over lyric sections. This is a matter of taste. A slightly faster approach would have made the music more shapely.

He played the three “Petrarch” Sonnets of Liszt quietly and songfully, with incredible technical control and an iridescent tonal quality. And listening to the “Tannhäuser” Overture was an experience.

Two generations ago it was a standard work for virtuoso pianists; today it has almost disappeared. It is a tour de force, and Mr. Bolet played it as such, yet never neglecting his major aim of tonal control. Piano music does not come any harder than this, but Mr. Bolet made it sound easy.

Later on, completely relaxed in his encores, he achieved wonders in the “Rigoletto” paraphrase, playing it with even more stunning impact than he had done a few years ago at the International Piano Library concert. Just as noteworthy was the finesse he brought to the Liszt song transcriptions by Schumann and Schubert. This was complete mastery. Jorge Bolet is one of the few pianists around who make one think of the great Romantic artists of a previous generation. [Harold C. Schonberg]

Recording of a Hunter College on 17 February 1973.

15 March, 1973, with the City of Birmingham Symphony under French conductor Louis Frémaux (1921-2017) in London. 'The only major orchestral conductor to serve two spells as an officer in the Foreign Legion, one of which was in Vietnam in 1945-46. Perhaps the experience of leading some of France’s toughest, most hardbitten troops assisted him in dealing with refractory or undisciplined musicians. On the other hand, his wish to have his own way contributed to the messy end of his memorable stint in Birmingham. Described by one critic as “gnarled and handsome”, Frémaux was admired for his flair, his wristy baton technique and the way he virtually danced on the podium. (Tully Potter). His tenure with the CBSO lasted 1969 to 1978, and he was succeeded by Simon Rattle.

On 8 May 1973, Jorge gave a recital at Butler University Romantic Festival, Clowes Memorial Hall, Indianapolis.

'Where does one begin in an attempt to describe the sensation created by Jorge Bolet in his recital last night in Clowes Hall? As a start, it can be reported that this pianistic giant snatched his program of Rachmaninoff and Liszt transcriptions from the jaws of death.

'In one of those mysterious accidents that occur to the greatest of artists, and Bolet numbers among them, the first selection, Rachmaninoff's version of J. S. Bach's Prelude from the Third Partita for Unaccompanied Violin, got away from him. Small errors become noticeable almost immediately and then that horror for all performers occurred, a memory lapse. Finally, Bolet flew through to the end only to hit a terrible clanger on the final note. From there the program became a steady rise...'

Michael Glover adds that 'After concluding this recital, Jorge Bolet paid a immediate visit to the radio engineer personally to oversee deletion from the master of the Bach transcription that had been the concert's opening item.'

'Bolet electrified the Clowes Hall audience to a fever pitch perhaps unparalleled in the annals of local solo piano recitals. One of the most thundering and long-lasting ovations ever seen in the hall.' (Tom Aldridge, recalling the Butler Romantic Music Festivals in Arts Indiana Magazine, June 1982)

Jorge's carnival piece, Godowsky's Symphonic Metamorphoses on Themes from Die Fledermaus

can be heard on Marston CDs Volume 2 from a performance on 7 May 1973, in Cologne/Köln, Germany.

The Gardens of Buitenzorg (No. 8 from Java Suite) on 28 November 1983, in Milan, Italy.

Post-concert festivities following upon Rachmaninoff's third piano concerto with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra under Izler Solomon in November 1973 attracted the attention of the 'Don't Quote Me' column of the Indianapolis News:

'Frank Cooper, the Butler University music professor, wrote his old friend Jorge Bolet long ago and offered to take him out to dinner after his performance. Bolet accepted and Cooper invited several people from the symphony and from the city's upper crust to join them at La Tour restaurant. After the pianist's outstanding concert, however, Bolet said he didn't want to go to La Tour. "Where do you want to go?" Cooper asked. Bolet made a suggestion that left blank expressions on the guests' faces, but finally they realized he was serious. And that's how a carload of people in full tuxedos and long gowns wound up at Steak-n-Shake drive-in on 38th Street, sipping strawberry milkshakes.'

On 17 May 1973 in Cologne, West Germany, Jorge was recorded in a studio broadcast playing Godowsky: Symphonic Metamorphosis on themes from J. Strauss II’s operetta Die Fledermaus. This can be heard on Marston CDs volume 2.

Alicia de Larrocha

A pianist much admired by Bolet gave a recital in Carnegie Hall on Sunday, 25 March 1973 at 3pm. She performed the complete Iberia suite - apparently this was one of the 80 times that she performed it complete; she last performed it in New York, to critical acclaim, in 1966.

The work was composed between 1905 and 1909 by the Spanish composer Isaac Albéniz. Iberia was highly praised by Claude Debussy and Olivier Messiaen, who said: "Iberia is the wonder for the piano; it is perhaps on the highest place among the more brilliant pieces for the king of instruments".

'One has no choice but to call ''Iberia'' excessive. This is not a condemnation, only a description of its essence. Isaac Albéniz's 12 piano pieces are a hymn to overabundance. He was a Catalan who spent much of his incredible childhood in the New World and his later productive years in Paris. But Andalusia was closest to his heart, and the florid vegetation of this music seems to rise up like a mirage out of the hot, dry Spanish landscape.

'The composer himself despaired of the troubles he was making for pianists, once complaining to Manuel de Falla, whom he met on a Paris street, that what he had written was unplayable and perhaps should be burned. Maybe ''rarely playable'' is the better term, which translates further into ''rarely heard.'' Items like the ''El Corpus Christi en Sevilla'' are discouraging to the ablest pianist who, having struggled through pages of profuse filigree, is punished, not rewarded, at the end by a coda which magnifies, even doubles, the problems preceding it. Many pianists work at ''Iberia'' in their studios, but few dare bring it to the recital stage.

'Miss De Larrocha is not the only pianist today who can play ''Iberia,'' but she is perhaps the only one who approaches it minus the palpable sweat and fear that exude from the recorded efforts of her competitors.' Her extraordinary ear 'seems able to command color and fineness of detail with an imperiousness that the musculature has little option but to obey.

'The newer playing is as sure and as interesting as it has been in the past. New York will have a chance to confirm or deny this on Nov. 22 when Miss De Larrocha plays ''Iberia'' complete at Carnegie Hall.'

Bernard Holland, The New York Times, 16 October 1988 (of her second recording for DECCA/London)

AdL with JB and Garrick Ohlsson, March 1972 (?or London, December 1974) source

South Africa, May 1973

The Rand Daily Mail 17 May 1973 states that Jorge had changed the programmes for his Pretoria and Johannesburg recitals, at the suggestion of friends assisting him in his SA tour. They wanted more Liszt, and he ditched the Spanish Rhapsody for Tannhäuser Overture.

In a piece by Joe Sack in the same paper on 23 May 1973, we are told that 'The famous Bolet brothers will both be in South Africa this year but Jorge on a recital and concerto tour, will leave the Rand just before Alberto arrives in July.' (Witwatersrand ["white waters' ridge" in English, rand being the Afrikaans word for 'ridge'], the ridge upon which Johannesburg is built and where most of South Africa's gold deposits were found.)

'Whenever we can arrange this, Jorge Bolet told me yesterday shortly after his arrival, nine years after his last visit on the Rand, we meet in different parts of the world and appear together.' What was originally intended to be purely a holiday visit to SA turned into a concert tour for Bolet when Johannesburg pianist Adelaide Newman persuaded him to devote part of his time here to recitals and recordings for the SABC

Jorge had brought a battery of cameras and telephoto lenses. 'With these I hope to get colour slides of the animal life in the Kruger National Park. and when I leave here in the wild life park near Nairobi.'

Jorge gives an account of his time just before departing for South Africa. 'After my recent Bakersfield, California concert with Alberto, I had five days of dashing across the country, from there to Saratoga, then on to San Francisco, New York, Indianapolis and then across the Atlantic to London. Almost as bad was last week's routine. I had two performances in Lübeck, Germany, the last one ending late at night, and then snatched a few hours sleep before leaving shortly after six the next morning for Bremen where recording sessions started at the radio station at 10am.'

Friday 25 May: lunchtime all-Liszt recital in Pretoria at the Musaion

(concert hall of the University, pictured above).

Sunday 27 May: recital Johannesburg Civic Theatre 3pm. He will also

perform in Durban (4/5 June) and Cape Town (7).

Jorge plays the Grieg concerto with the SABC orchestra in Johannesburg

City Hall on May 29 and 30. Edgar Cree conducted Nielsen's third symphony

after the interval.

The Rand Daily News 30 May 1973 questioned 'Are transcriptions really

necessary when there is a wealth of original literature? Yes, when a pianist with the power and insight of Bolet plays them.' That Sunday concert had included Brahms' Sonata in F minor op.5, and Liszt's Gnomereigen.

Bill Brower in The Sunday Times (J'burg), 27 May 1973 said that today wasn't his cup of Sunday afternoon tea. Brahms' Sonata in F minor Op. 5, 'a complex and perplexing gambit, prolific in its technical demands, which were marvellously met but it lacked the (John) Ogdon hand of gentleness. I longed for a singing piano string, not merely exploding cascades of tonal dynamite. Liszt filled the second half, an hour almost totally devoid of human feeling. Gargantuan effort was there in abundance... What was missing for me were the unfathomable depths which no human accomplishment or instrumental arrangement can plumb, as for example, in The Art of Fugue or the Grosse Fugue. I suppose when you climb Everest, the feelings do become numb.' [Not convinced by his final sentiments! (Editor)]

E. Ahlers for Die Transvaler (29.5.73) was more convinced, talking both of a pianist's dream of a technique and of considered musical depth (oorwoë musikale diepgang). The powerful and sparkling scherzo was the highlight of this work (is he speaking of Brahms or of the pianist?). Jorge played the Tannhäuser overture and two encores, Liebesträum 3 and Widmung.

Die Transvaler (named after Transvaal province, once part of the Boer republics) was established in 1937 as a newspaper that would promote the cause of Afrikaner nationalism within the Afrikaner-dominated National Party. Edited by Hendrik Verwoerd—future prime minister and architect of the apartheid regime—Die Transvaler was notorious for its racism, antisemitism, and opposition to South Africa’s entry into World War II.

In 1948, the National Party won its first election in a decade and, shortly thereafter, implemented apartheid. The apartheid regime stripped non-white South Africans of their political rights and strictly limited their housing, travel, employment, and social opportunities—using a surveillance and violence to enforce its policies. The pinnacle of Die Transvaler‘s influence was in the 1960s and early 1970s, under the governments of Afrikaner nationalists Hendrik Verwoerd and B.J. Vorster.

RCA Rachmaninoff transcriptions LP

In July 1973, Jorge made a recording in RCA Studio A, New York City, New York: "Great Rachmaninoff Transcriptions" (7,10,12,13,16 July)

· Kreisler/Rachmaninoff: Liebesfreud (from Three Old Viennese Dances)

· Rachmaninoff: Polka de W.R. (after F. Behr’s Lachtäubchen, Op.303)

· Tchaikovsky/Rachmaninoff: Lullaby, Op.16 No.1

· Bizet/Rachmaninoff: Minuet from L’Arlésienne

· Rachmaninoff: Prelude in G-flat major, Op.23 No.10

· Rimsky-Korsakov/Rachmaninoff: Flight of the bumblebee (from The Tale of Tsar Saltan)

· Kreisler/Rachmaninoff: Liebesleid (from Three Old Viennese Dances)

· Mendelssohn/Rachmaninoff: Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

· Rachmaninoff: Prelude in G-sharp minor, Op.32 No.12

· Bach/Rachmaninoff: Preludio from Violin Partita No.3 in E major, BWV 1006

· Mussorgsky/Rachmaninoff: Hopak (from Sorochyntsi Fair)

Jorge kept wanting to repeat things but was told to stop. 'We are happy,' cried the producer, 'and so is Mr Rachmaninoff!'

By a set of curious circumstances, we also have a complete, unedited performance of Wagner/Liszt: Overture to Tannhäuser, S.442 from this session, but it only was issued thirty years later (see above August 1972).

Jon M Samuels, RCA producer, explains: 'On July 16, Jorge finished taping the fiendishly, difficult Rachmaninoff transcription of the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream and the composer's own Polka de W.R. He apparently then decided to play a run-through of the Overture before leaving the studio. The engineers were running two machines in tandem at the time (standard industry practice), but were clearly caught off guard. On one machine, they missed the first eight minutes and on the other they were barely able to start it in time to get the first note. Only by overlapping the tapes from the two machines were we able to get a complete performance. The recording session ended with this run-through, and what we hear is exactly what Bolet played.

There are no edits, performance changes or musical corrections of any kind.'

Summer 1973

In August, Jorge played at the Maryland Piano Festival. Stewart Gordon had said that 'In 1973, I learned that Bolet had not played a recital in the Washington D.C. area for more than ten years, an unbelievable fact considering the scope of his career. The Festival audience was waiting in great anticipation for him to step out on stage and play.' He began with Chopin's 4 scherzos, and there was a even standing ovation after No. 2 in B flat minor!

Gordon recalls that one year a pianist cancelled within 48 hours and, after frantic searches for a replacement, 'I suddenly got the idea of telephoning Bolet's apartment in New York on the off-chance someone might pick up.' Tex Compton did pick up but explained that 'Jorge is in town, ok, but had set aside this week for dental surgery, something which he had been postponing for weeks and which was not overdue. As a matter of fact, he is at the dentist now.' But Tex contacted the dental surgery, and then called Gordon back to say that though Jorge's mouth was full of novocaine, he readily agreed to be there for the recital the night after next.

Saturday, 25 August 1973, Gibraltar Auditorium, Fish Creek, Wisconsin. Sgambati, Concerto in G minor along with Mozart 39th Symphony in E flat and Copland's Appalachian Spring. Part of the 21st Peninsula Music Festival; conducted by Dr Thor Johnson (who founded the festival and had accompanied JB in the Prokofiev 2 recording with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, a landmark recording in that it was the first recording ever made of this work). Jorge was interviewed by The Door County Advocate (28.8.73): '"The US allowed the Cuban situation to develop," Bolet states firmly. "This is due to a national reluctance on the part of American to look the problem of Communism straight in the eye. Americans tend to think Communism is not as bad as it really is. I am a rabid anti-socialist." As a final remark, Bolet recommended reading The Fourth Floor by Ambassador Smith. The book records the progress of Castro's rise to power.'

The book to which Jorge refers is The Fourth Floor. An Account of the Castro Communist Revolution, by Earl E. T. Smith (New York, 1962)

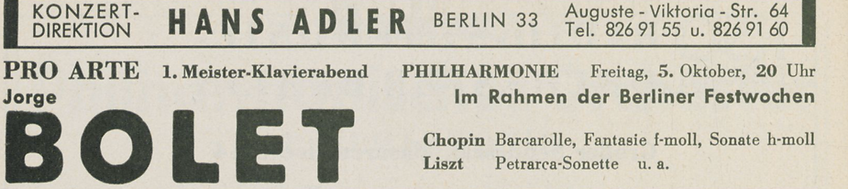

Friday, 5 October 1973: Meister-Klavierabend Philharmonie, Berlin: Chopin Barcarolle, Fantasie f-moll, Sonate h-moll Liszt Petrarca-Sonette u. a. (see below)

Wednesday, 10 October 1973, Colston Hall, Bristol UK: Rachmaninoff 3 with the Bournemouth Symphony and Paavo Berglund. The programme also included Vaughan William's' 6th symphony and Panufnik's Heroic Overture. Sir Andrzej Panufnik (1914 – 1991) was a Polish composer and conductor. He became established as one of the leading Polish composers, and as a conductor he was instrumental in the re-establishment of the Warsaw Philharmonic orchestra after World War II. He also served as Principal Conductor of the Kraków Philharmonic Orchestra. After his increasing frustration with the extra-musical demands made on him by the country's regime, he defected to the United Kingdom in 1954, and took up British citizenship.

Tuesday, 4 December 1954, first appearance in five years in Orchestra Hall, Chicago with the Chicago SO. ??

1974

Geneva, Switzerland, 23 January, 1974: Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953), Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Wolfgang Sawallisch, conductor.

Live concert at the Victoria Hall, Geneva; Swiss Radio live broadcast.

Gazette de Lausanne, 26.1.74 reported that 'Jorge Bolet, a splendid artist of rare intelligence and emotional power, knew how to articulate the sequence of these pages with incredible brilliance: the prodigious cadence of the Allegretto, the vivacity of the Scherzo, the marvellous lyricism of the Russian theme of the Finale took on a tragico-epic meaning under his fingers. His art of timbre attained incredible subtlety. The accompaniment was also remarkable for its precision and breadth.'

(There was another performance in the University Hall, Fribourg on Friday 25.1.74)

28 February 1974: Heinz Hall, Pittsburgh. Jorge replaced an indisposed Radu Lupu in Beethoven's 3rd concerto with Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos.

Radu Lupu CBE (30 November 1945 – 17 April 2022) was a Romanian pianist. Born in Galați, Romania, Lupu began studying piano at the age of six. Two of his major piano teachers were Florica Musicescu, who also taught Dinu Lipatti, and (going aged 16 to Moscow) Heinrich Neuhaus, who also taught Sviatoslav Richter and Emil Gilels. From 1966 to 1969, he won three of the world's most prestigious piano competitions: the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition (1966), the George Enescu International Piano Competition (1967), and the Leeds International Pianoforte Competition (1969). These victories launched Lupu's international career.

(*He had performed Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 3 with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra under Charles Groves (Op. 37) in the Leeds final.)

In 2016 was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2016 New Year Honours for services to music.

In a 2002 interview, Japanese-British pianist Dame Mitsuko Uchida said of Lupu that "there is nobody on earth who can actually get certain range of colour, and also the control – don't underestimate this unbelievable control of his playing".

25th February, 1974 at Carnegie Hall

‘Stung by years of neglect’,

Bolet roared to the heavens –

and the microphones were there

to witness it.

The most important event, conceivably, in his career awaited Jorge in February in that battleground of the pianistic giants, Carnegie Hall. He'd played there before, quite a few times in fact, but 25 February, at half past eight in the evening, turned out to be different. 'I am big, it's just that the public now got me', to adapt a famous line from Sunset Boulevard.

It was a courageous and unforgettable programme of mammoth transcriptions, ending with Liszt’s version of the Overture to Tannhäuser, Bolet piling Pelion upon Ossa in the incremental programme (as one critic put it). (Pelion and Ossa are two mountains in Thessaly, in northern Greece, and the phrase alludes to Greek mythology: two giants, Otus and Ephialtes, tried to pile Pelion and Ossa on Olympus in order to reach the gods and overthrow them.) Somehow an original composition - Chopin’s Preludes Op.28 - got into the mix!

'As one of the most prominent pianists of the romantic revival, Jorge Bolet put on his program a great deal of music that was popular at the turn of the century but that has since slipped into disrepute. The audience reaction he evoked, with a standing ovation and all, showed that there is life in the old girls yet.

'Mr. Bolet has a technique equal to any in the world today, and in music that is a technical stunt, such as the Schulz‐Evler “Blue Danube,” he does bring that element to the fore. On the whole, however, his playing is if anything reserved. There is an element in Mr. Bolet's make‐up that obviously shrinks from pointless display, and often as a result he will underplay.

'It was in many respects a remarkable concert — the playing of a stupendous workman at the piano determined to prove that certain aspects of the repertory remain viable when played with the charm and pianistic finish that the giants of the past used to bring to it.'

The “Tannhäuser” Overture in Liszt's transcription: 'Naturally it brought down the house. For encores, Mr. Bolet came up with three more forgotten pieces. The dead past lived once again under Mr. Bolet's fantastic fingers.'

Mel Taub, The New York Times 27 February 1974

In September, Eric Salzman reviewed the LPs when they were issued. Of the Chopin Preludes: 'There was no hyphen involved in these, but the program might just as well have read "Chopin-Bolet", for he takes every possible expressive liberty, playing off the beat, sustaining tones, arpeggiating chords, creating new lines and cross -rhythms, playing fast and free with the tempos, even changing the text here and there. Yet all of it has such authority and sensibility of touch, nuance, color, line, and phrase that one ends up agreeing with Bolet and not the dry-bone notes of the printed music! He re-creates it all afresh.'

Concerning the transcriptions of Viennese waltzes (by Carl Tausig and Schulz Evler): 'In a way, it's a pity that so much skill - and I mean musicality, sensitivity, swiftness, sureness, taste, and communicativeness, not mere facility - is tossed away so lightly, so prodigally, on so many soap bubbles.'

Here is Jorge's performance of J.Strauss/ Schulz-Evler, "Blue Danube" 26 May 1974 in Arnhem, Holland, bubbles, froth, spume, foam and all...